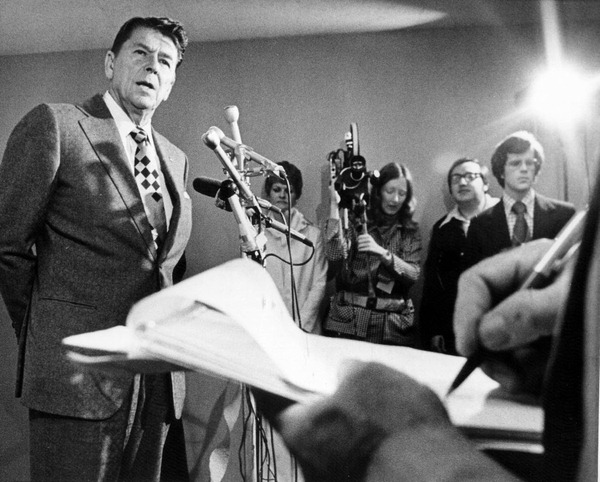

Ronald Reagan’s Close Encounters With the Fourth Estate

On the evening of Ronald Reagan’s election as the fortieth president of the United States, Walter Cronkite had just announced a Republican sweep of Illinois when Reagan, following a brief victory speech, began moving out through a crowd of enthusiastic supporters at the Century Plaza Hotel in Los Angeles. Former president Gerald Ford had joined Cronkite in the CBS anchor booth in New York, and Cronkite was angling for a way to hook the two of them up electronically for a congratulatory chat.

CBS’s alert correspondent at the Century Plaza, Jerry Bowen, accepted a kiss from Nancy Reagan and then asked her to retrieve her husband for the CBS cameras. “I’ll try,” she said. Mrs. Reagan eased her way through a crush of well-wishers, tugged her husband on the elbow, and brought the new president-elect to Bowen. The CBS reporter was prepared to relay questions to Reagan, but Cronkite said, “Jerry, let me suggest something to you. Because the audio is much better, why don’t you take off your headset and see if Governor Reagan would put it on.”

With no trace of hesitation —and with apparent recognition of what was about to happen —Reagan did exactly that. He and Ford exchanged pleasantries, and Cronkite followed with a few questions. In a matter of minutes, with Ronald Reagan’s smooth acquiescence, Cronkite and Bowen had scored a beat over their network rivals.

The memorable election night vignette illustrates Ronald Reagan’s familiarity and ease with the television technology that catapulted him to political stardom and into the White House, a technology that has come to dominate — if not overwhelm — modern news coverage of election campaigns. One cannot easily imagine, say, Jimmy Carter or Richard Nixon handling the incident with the same aplomb. The scene also underscores what appears to be Reagan’s unflagging desire to accommodate the reporters who cover him, sometimes against the wishes of his own advisers.

Ronald Reagan has been in political office — or in pursuit of it — for a decade and a half and is unquestionably a master of the medium of television. Looking back on his early days as a motion-picture actor, Reagan has said his greatest challenge was to rise above his lines in often mediocre scripts. In his second career, the skill has served him well: Reagan knows that the image he can create is just as important as the message itself. His deft projection of simplicity and sincerity, the two words Reagan acknowledges are at the heart of his success, have crystallized the public’s perception of his character and motives through the years and given him an important edge over his opponents.

Considering how long Ronald Reagan has been in the public spotlight, little is known about his attitudes toward the press and his understanding of its role. Does he view reporters — as Lyndon Johnson did — as pawns in a manipulative chess game for public opinion? Deep down, does he harbor — as Richard Nixon did — an abiding fear of the press and a dark distrust of its motives? Does Reagan believe — as Jimmy Carter did — that journalists are addicted to reporting conflict, confusion, and scandal, thereby handicapping a president’s capacity to govern effectively

Reporters who have covered Reagan as governor of California and on the presidential campaign trail say the answer to each of these questions is no. Ronald Reagan is, they say with remarkable homogeneity, a man at peace with himself — confident of his own performance before the press and comfortable in the company of journalists. But in their professional, give-and-take relationship with Reagan (and very few — if any — enjoy something more than that), reporters agree that he is very much a “programmed” performer. As a result, they often are left to wonder whether their perceptions of Reagan square entirely with reality.

Washington Post reporter Lou Cannon, generally acknowledged by his peers in the press corps to be its foremost Reagan expert, says an “integrated personality” is an important part of the new president’s character. “He knows who he is, he’s happy with who he is, and that governs an awful lot of things,” Cannon says. “I think it had a lot to do with the election. He’s confident of himself as a human being, and with reporters, like with any other group of people, he believes in himself and believes in what he’s talking about.”

“I think Reagan basically likes reporters,” says NBC correspondent Don Oliver. “He likes anybody who’s been around him for some time. He even likes people who have written nasty things about him if he’s known them for a while.”

“I think Reagan realizes that he wouldn’t have been elected president without all of those cameras, without all the print people following him around,” says David Hoffman, who covered Reagan on the campaign trail for Knight-Ridder Newspapers. “He takes a charitable, benign view of the press.”

In his 1965 autobiography, Where’s the Rest of Me?, Reagan wrote: “It has taken me many years to get used to seeing myself as others see me. Very few of us ever see ourselves except as we look directly at ourselves in a mirror. Thus we don’t know how we look from behind, from the side, walking, standing, moving normally through a room.”

The passage is revealing, for it helps explain why Ronald Reagan is so artfully at ease before a crowd or in front of the television cameras. Even his political detractors have been forced to admit that, as a television performer, he not only is good, he is very good. While trepidation may linger in the gut of other politicians, Reagan approaches the cameras with an assured, knock-’em-dead poise. After a faltering start in the Iowa caucuses, longtime friends and political advisers zeroed in on the problem: Reagan’s greatest asset was going to waste because campaign manager John Sears had decided to keep the candidate under wraps and above the fray.

The revised, post-Sears strategy was aimed at increasing Reagan’s acessibility to the press, but largely as a means of showing him as a vigorous, durable candidate. For the most part, Reagan was kept well-rested and relaxed for optimum performance, and the campaign was weighted heavily toward television. “Lyn Nofziger [Reagan’s former press secretary] made no bones about the fact that television reached more people and that he desired the candidate to be seen on television as often as possible,” says Bill Plante of CBS News.

Even though many print reporters on the campaign trail complained that they were treated as second-class citizens by Reagan’s managers, they found the candidate himself almost always ready and willing to answer their questions. “Through the primaries and the convention, he was a very accessible candidate,” says Knight-Ridder’s Hoffman. “I can remember in the campaign when we had five press conferences a day. And you could ask Reagan anything — he would stand there and wait until we were done.”

An essential part of the Reagan style is his apparent reluctance to cut off questions from reporters, and often his staff must do it for him. “He does seem to be concerned that he will offend the press by not answering their questions,” says Richard Bergholz of the Los Angeles Times. “The staff always arranges to cut off the questioning because it’s very hard for him to do it. He’ll say, ‘Well, I’ve got to go,’ and somebody will yell at him and he’ll answer one more. He’ll start fidgeting, but he won’t walk away.” Lyn Nofziger’s various techniques of interposing himself to stop the interrogations became legendary in the press contingent. Was the procedure planned to cast a staff member — and not Reagan — as the heavy? “I never had the sense that Reagan was doing it on purpose so that he would look like a nice guy,” says Plante. “But he’s not dumb — he must be aware that that’s the case as well.”

Most reporters were pleased by the easy access to Reagan during most of the primary campaign, but they often were less than happy with the answers they got from him. Reagan’s memory of the printed word is nearly photographic, and he has the uncanny ability to summon entire sections of stock speeches and recite them as seemingly off-the-cuff answers — with practiced gestures and inflections that give them the necessary touch of spontaneity. Journalists were left with the impression that for virtually any question put to Reagan, his response was neatly retrieved from a vast mental inventory of paragraphs long ago recorded on the three-by-five cards that became his trademark.

The same could not be said for some reporters, though, and Reagan’s time-worn answers frustrated them and made their access to the candidate seem almost redundant. “It got to the point during the primary season,” says NBC’s Don Oliver, “that I got so goddamned tired of interviewing Reagan I would have given almost anything not to have to do it. Because he doesn’t say a whole lot. You ask him a tough question, and he’ll think of a way to bring it back to something he’s comfortable with rather than answering questions directly. “

“I can recall only rarely asking him a question, or a colleague asking a question, that startled him or surprised him or took Reagan off-guard,” says Hoffman. “He’s an amazing person in that respect. There are some candidates — George Bush was one — who would get nettled at certain questions and be visibly irritated with them. Reagan was the kind of guy who would usually take anything you threw at him because he had handled it all before. He had almost what I would call a ‘push-button’ response to just about every kind of question. And, as a result he sort of reveled in it.”

Journalists point to other quirks in Reagan’s question-answer style. Unlike most other politicians, Reagan does not seem to mind admitting he does not know the answer to something. The habit apparently goes back to his days as governor of California, when reporters and state legislators would lay wagers on how many times Reagan would say “I don’t know” during one of his Sacramento news conferences. And on the campaign trail, according to reporters, Reagan almost invariably answered those questions shouted most loudly at him. (Some believe this was due to Reagan’s hearing problems, and was one factor in the revised ground rules — “keep your mouth shut and raise your hand” — for presidential news conferences.)

Reagan provided reporters covering him in the 1980 campaign with few glimpses of downright anger over news coverage. What seemed to bother Reagan most about the press, say reporters who covered the campaign, was its dogged, collective pursuit of more expansive answers to significant policy questions. And he grew testy during several stages of the campaign when journalists highlighted his shoot-from-the-hip gaffes, explored his use of questionable facts and statistics to embroider speeches and off-the-cuff responses, or, in one case, reported an ethnic joke he had told. “Reagan has a temper, but he doesn’t show it very often,” says Oliver. “I recall one interview I did with him, where I kept pressing him on how he was going to be able to cut taxes by ten percent a year, still provide enough money in the defense budget, and not have to cut any federal programs. He kept giving me standard answers and I kept pressing. So I asked, ‘What if it doesn’t work?’ Right back came: ‘What if it doesn’t work? At least it’s worth a try — it’s better than what we’re doing now.’ It’s one of the more honest answers I ever got from him. But it got to a point where I think he was a little exasperated that I wouldn’t accept the same answers over and over again.”

Even when Reagan is rankled, he apparently adopts a forgive-and-forget attitude toward journalists. Says Bergholz: “You press him and, hell, he’s gotten mad at me. He gets very, very sensitive, and he’s accused me of nitpicking. If you look at the transcript [of a press conference] you may see that it was a rather bitter exchange, but he’s never carried a grudge as far as I know.”

Why does Reagan —unlike so many other politicians — seem to have such a benign and forgiving attitude toward the press? Perhaps the best explanation comes from Edward Langley, a public-relations specialist who worked closely with Reagan during his years as the corporate spokesman for General Electric (GE). In what Langley calls “the greatest accidental political training program ever,” Reagan gave more than 9,000 talks to groups of GE employees, chambers of commerce, fraternal organizations, and the like. He met more than a quarter of a million people over eight years, and frequently was bombarded with stinging, even savage, questions (“How much are they paying you for this shit?”).

“The key to unlocking Ronald Reagan,” Langley’recently wrote, “lies in the haystack of those eight grinding years at GE where he was battered, molded, toughened by being pressed against the people. He has plenty of scar tissue to show for it and drubbings can’t hurt much anymore.”

Journalists who meet Reagan for the first time often come away with the same impression of him: a relaxed, affable man who exudes charm, humility, and good humor. The portrait, at least to reporters, is in sharp contrast to Jimmy Carter’s, who often seemed stiff and uncomfortable in their presence. “Reagan loves to sit around and bullshit, he likes to tell Hollywood stories, and he likes to be around people who tell a nice off-color joke — he gets a kick out of that,” says Oliver. “He’s much more relaxed than Carter ever was. Carter was always on guard. And if Reagan has a catastrophe, he’ll laugh at himself. “

While Reagan seems entirely comfortable in the presence of reporters, he decidedly is not close to them. Ask reporters who have covered Reagan whether he has any friends in the media, and their answers seem like echoes. From the Washington Post‘s Lou Cannon, “I don’t know that there’s anybody in the press corps who would be a confidant, who would have a relationship that would be that close.” From Bergholz: “Reagan just isn’t the kind to be socially close to the media, as far as I know.” And from Time magazine’s Laurence Barrett: “He has almost no warm friends or deep enemies among the press. Unlike almost every politician I’ve ever met, he makes next to no effort to massage individual reporters, and I don’t mean that as a criticism of him. Not that he is hostile, not that he is stiff, but certainly it’s clear that he doesn’t want to be ‘pals,’ and makes no effort to be.”

Journalists seem to be at a loss to pinpoint the reason. Reagan is not really aloof, they say, but he does try to place some professional distance, or reserve, between himself and reporters. “I’ve never been in a situation with Reagan where I really thought he was letting his hair down,” says Drake. Reporters agree that Reagan will virtually never mention — or even acknowledge reading —stories they have written about him. “To the best of my recollection,” says Barrett, “He never, never alluded to any of the articles Time published about him in subsequent conversations with me. [Reagan was the magazine’s “Man of the Year” in 1980.] I knew he read the stuff — I heard back from others that he had mentioned reading it. But he never mentioned reading them to me. It was almost as if we were starting fresh.”

Members of Reagan’s staff knew that their candidate was generally perceived by the press as “a nice, decent guy,” but at the same time, their own polling data from the primary campaign showed that he was seen by many in the electorate as a trigger-happy arch-conservative. It is a testament to Reagan’s aplomb and craftsmanship before the television cameras that, following the GOP convention, he was able to soften that public perception.

Within the Washington press corps (and, presumably, within the White House) there is optimism for an open relationship between President Reagan and the press, but it is tempered by experience and professional caution. “I expect it to be a lot more open than the Carter administration was,” says Gary Schuster, Washington bureau chief of the Detroit News. “That expectation is based on Reagan’s past performance, but also the fact that Reagan uses the press corps — he knows he does well and his staff knows he does well. I don’t think there will be a ‘bunker mentality,’ unless he gets burned someplace along the line. Then, they may pull their heads in — and that’s very likely to happen.”

Journalists will be looking to both Reagan himself and the White House staff for signals that something has gone sour. “The first warning sign will be this: Reagan will blame the press for some mistake that he or his staff has made,” says Cannon. “Reagan will say he has been misquoted when he has not been misquoted. I’m not talking about some story that finds its way into some column about how he got pissed off at something he thought was inaccurate and said it to his wife or staff. That’s an absolutely necessary safety valve. I mean if he’s passing off his own mistakes as a press thing, that’s always a warning sign with Reagan.”

“I think it all goes back to whether or not Reagan, in fact, is going to be running things or other people are going to be running them for him,” says Oliver. “And I think there are a lot of signs that point to the latter rather than the former. There were so many times during the campaign when it was obvious that he knew nothing about decisions that were being made in his behalf. And it’s when he has let people manipulate him that he has gotten into trouble. And the same thing might happen in the White House in his relationship with the press corps.”

But the press is likely to have a more basic problem with Reagan, a problem that goes to the heart of all press/president relations. And in Reagan’s case, its shape is almost the mirror image of the press’ problem with Jimmy Carter.

Throughout his four years in the White House, Jimmy Carter served up in abundance the specifics that reporters today so determinedly seek from Ronald Reagan. Many said he took an engineer’s approach to the job, becoming so mired in minutiae and detail that the broad picture of governing eluded him. Journalists were frustrated, as apparently was the electorate, by Carter’s seeming inability to carve out a coherent vision of his own administration’s goals. As former Carter speechwriter James Fallows wrote, it was a “passionless presidency,” unguided by ideology.

Ronald Reagan, on the other hand, provides plenty of ideology, a “simple and sincere” vision of conservatism sharpened over more than two decades spent traveling across America. After four years of Jimmy Carter, Reagan’s philosophical passion and simplicity paint an appealing picture. The question is, as the press now seeks to cover a very different sort of man in the White House, how much reason and substance lie behind that vision?

How hard journalists press that question — and how effective Reagan is in answering it —will determine the course of his relations with them. And the course, perhaps, of his presidency.

Sidebar: What Reagan Reads

This article originally appeared in the March 1981 issue of Washington Journalism Review.