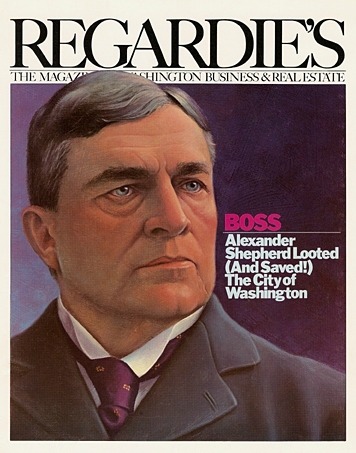

Boss

When cartoonist Thomas Nast of Harper’s Weekly laid pen to paper in the spring of 1874, it no longer was poised to savagely ridicule William Marcy “Boss” Tweed. Three years earlier, after a long reign as the crooked kingpin of New York’s Tammany Ring, Tweed had been convicted of larceny and forgery and put behind bars. Nast’s cartoons had had a lot to do with it.

Now, from 250 miles north, Nast set his sights on the governor of the District of Columbia, Alexander Robey Shepherd. Like Tweed’s New Yorkers, Shepherd’s Washingtonians called him Boss, too. And for good reason. During Shepherd’s brief tenure as iron-fisted dictator of the District’s only experiment in self-government, virtually no one of power or influence — right up to the president of the United States — dared to challenge his reckless and ruthless audacity.

Like Tweed, Shepherd was a caricaturist’s dream come true. He was a moose of a man — tall and massive-shouldered, foul-mouthed yet well-mannered, with a bullhorn for a voice — a street-smart bully imbued with the class and charm of upper-echelon Washington. His craggy face was etched with a don’t-mess-with-me visage, and the message carried well. Shepherd elbowed his way to political power at the dawn of America’s gilded age, and the regime he ruled — first as head of the Board of Public Works and later as governor of the District of Columbia — had no equal for municipal graft and corruption squeezed into just a few ears, even when placed alongside the infamous Tweed Ring.

He found the city of his birth an ugly and foul-smelling morass, ill-befitting the grandeur envisioned by the nation’s founding fathers. As the architect of the most massive and intensive public-works extravaganza in Washington’s history, Shepherd flattened it out and cleaned it up, but left the city mired deeply in debt instead of mud. In just under three years, he shamelessly showered $30 million around the streets of Washington — tens of millions of dollars more than the federal government had authorized, tens of millions more than the city’s citizens could afford.

Much of the money wound up in the pockets of Boss Shepherd and his cronies (no one has ever figured out how much), and the rest helped transform a squalid, Southern village into a modern network of streets, avenues, and magnificent boulevards, parks and circles, excavations and fills, sidewalks and sewers. Shepherd’s scheme was on such a grand scale that most Washingtonians were afraid to let it stop, lest the city look like something halfway between a frontier settlement and a metropolis.

By the time Thomas Nast’s pen zeroed in on Boss Shepherd, however, he was something of a lame target. For the first time in his life, Shepherd was running scared, in danger of being overcome by events beyond his control. The great financial panic of 1873 had loosened his tight grip on the District’s territorial legislature. Public indignation over rumors of wholesale crookedness in Shepherd’s “Washington Ring” reached a fever pitch, and Congress had little choice but to look into the matter, even though a special House committee had done exactly that less than two years before, claiming it could find little wrong with either Shepherd or his methods.

But this time, the joint congressional committee was not stacked so neatly in Shepherd’s favor when it began its investigation in February 1864. Sitting every day for the next three and a half months, it called more than one hundred witnesses (including, of course, Shepherd) and dutifully compiled thousands of pages of testimony, which in sum amounted to a damning catalogue of corruption. During the earlier House investigation, Shepherd had promised to begin keeping a complete record of all the money he was spending, but two years later, the books still were in total disarray. By piecing together the fragmentary records, the joint committee determined that at least $26 million in contracts had been let, even though Shepherd had been legally authorized to spend only $4 million. When asked to account for the astonishing discrepancy, Shepherd gamely told committee members he expected the federal government to foot half the bill, a kind of creative financing that took Congress and the District’s taxpayers by surprise.

In a desperate effort to shift blame for the territorial government’s sorry financial shape, Shepherd suggested the legislature ought to be dissolved — at least until Congress could figure out whether it was needed at all. But the committee refused Shepherd’s invitation, and placed the blame squarely on the doorstep of the entire territorial government — or, more precisely, on the District’s Board of Public Works, from which Shepherd had climbed to power.

In a frenzied rush to finish its work before the end of the session, the committee admitted the entire arrangement had been a mistake from the start and found the territorial government guilty of gross mismanagement. Without a word of debate, Congress then pulled the rug out from under the territorial government and summarily replaced it with a three-member Board of Commissioners, to be appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate. But most remarkable of all, Boss Shepherd escaped without as much as a reprimand.

Many speculated that his close relationship with President Ulysses Grant (a relationship that later was found to have included some lucrative business deals) saved Shepherd from congressional censure. But his friend in the White House stumbled into a hornet’s nest when he nominated Shepherd to serve on the new governing triumvirate. Typical of the resulting outrage was a Thomas Nast cartoon of July 1874. It depicts the robed figure of justice pointing a finger of scorn at a seated Grant, who is reaching for a newspaper on the floor headlined “Shepherd.” As a top-hatted Shepherd ducks out another door, she says to Grant: “Don’t let us have any more of this nonsense. It is a good trait to stand by one’s friends, but — ”

The Senate apparently agreed. In a single fit of revulsion, it tabled the nomination by a vote of 36-6 and sent Boss Shepherd, against his will, back to private life.

THOUGH IT IS BARELY IMAGINABLE TODAY, the Washington of 120 years ago was more of a national cesspool than a national capital. At the outbreak of the Civil War, it was a ramshackle town of 50,000. The federal government’s policy toward its home was one of not-so-benign neglect. In the first 70 years of the 19th century, for example, the federal government spent a little more than $1 million for improving the city’s thoroughfares; residents of Washington were forced to cough up nearly $14 million.

When it rained, Washington, already swampy, became one vast mudhole. Except for a few blocks downtown, the streets were not paved at all. (The magnificent boulevards carefully laid out by Pierre L’Enfant — covering more than half the city’s acreage — also were magnificently expensive, beyond the means of a less-than-prosperous Washington.) Carriages got hopelessly stuck in the mud and fire equipment often had to negotiate the sidewalks (if they could be found) to make any progress in reaching the scene of a blaze. Surface gutters provided the only drainage — there was no sewer system — and they were overgrown with weeds and filled with green slime. During heavy rains, minor tidal waves of garbage and filth washed over much of Washington.

If there had been any impulse toward improvement of these deplorable conditions, the onset of the Civil War quickly ended it. Columns of army wagons rolling through the city got mired in the mud and cut even deeper ruts into the roads. As the fighting went on, poor blacks swarmed into Washington, and at the end of the war, they were joined by a high tide of drifters, riff-raff, assorted hangers-on, and thousands of others who, once in the nation’s capital, could afford to go nowhere else. In just 10 years, from 1860 to 1870, the city’s population more than doubled to over 100,000, only worsening the problems that already existed. Tracts where rents were cheap and human health and life in peril — places with names like Murder Bay, Swampdoodle, and Hell’s Bottom — sprung up in Southwest Washington.

The two-mile-long Washington Canal, once navigable, became a vast, stagnant fermentation vat, into which was dumped 300,000 cubic feet of waste each year. It was nothing more than an open sewer, exposing a festering mass at low tide; when the water was high, dead cats and dogs — and on occasion, human corpses — as well as all kinds of garbage, floated on the canal’s scum-covered surface. The same was true of one of the canal’s tributaries, the Tiber, which ran through the middle of Washington to the Potomac River from the north slope of Capitol Hill.

These filthy waterways were blamed for periodic outbreaks of malaria and smallpox, and it became impossible to walk through much of Washington without keeping the hand to the nose. Decades earlier, statesman John Randolph had said a Washington pedestrian should provide himself with an overcoat, a duster, a pair of rubber shoes, and a fan. To the great consternation of local residents and merchants, it was still very good advice.

Pigs, goats, cattle, and geese roamed through the city at will, scattering mounds of garbage dumped into what passed for streets. Some pigs made the gutters along Pennsylvania Avenue their home; others were provided with permanent pens by Washington homeowners, who fed the pigs their garbage (it was the only halfway sanitary way to get rid of it).

Things had gotten so bad in Washington that a movement began gathering steam to put the nation’s capital somewhere else. The New York Tribune’s Horace Greeley, who hated Washington, described it in the late 1860s as a place where “the rents are high, the food is bad, the dust is disgusting, the mud is deep, and the morals are deplorable.” He urged that the capital be transplanted somewhere in the Mississippi Valley, preferably near St. Louis. The Chicago Tribune joined in, launching an editorial campaign endorsing the recommendation of an 1869 convention of Southerners and Westerners that the nation’s capital be moved.

This kind of talk was not at all comforting to those who owned businesses in the District of Columbia. They stood to lose virtually everything if the seat of government — and the wellspring of their prosperity — were to be snatched out from under them. The city of Washington seemed to be sinking into its own muck, and the federal government did not appear to be interested in doing anything to remedy the situation. So a group of local business leaders decided that something must be done — and done quickly — to improve conditions in the nation’s capital and thereby safeguard their investments. One of the group’s organizers was a prosperous businessman involved in plumbing and gas-fitting, real estate, construction, and banking. His name was Alexander Robey Shepherd.

HE WAS BORN ON THE LAST DAY OF JANUARY IN 1835, in a section of Southwest Washington known as the “Island” because it was cut off from the heart of the city by the Washington Canal. His father had come to Washington in 1822, running a farmers’ hotel for several years, and then entering the lumber business. He soon became the District’s leading lumber merchant, but his failing health prompted the family to move to a “country home” in what is today Rock Creek Park, where he died at the age of 42. A rather comfortable estate was ill-managed and squandered by its executors, and Mrs. Shepherd was forced to support the seven children, of which Alexander was the oldest.

Three years after his father’s death, Shepherd, at 13, left a preparatory program at Columbian College (today George Washington University) to take a job as a store boy and help support the family. After two years in what he thought was a dead-end job, Shepherd decided to learn a trade and became a carpenter’s apprentice. But that really didn’t suit Shepherd either, and at the urging of his pastor, he quit to take a job with John W. Thompson & Company, the city’s leading gas-fixture and plumbing supply firm.

In short order, Shepherd became the company’s chief bookkeeper and accountant, then a full partner. When the Civil War broke out, the ranks of the city’s crack military company, the National Rifles, were thinned by two-thirds as a result of Southern sympathies rampant in Washington. Shepherd and his brother signed up for three-month terms in the Union Army. The contacts Shepherd made during his brief and undistinguished stint in the militia helped the Thompson firm increase its business with the government, and it soon was to become the largest plumbing and gas-fitting firm south of New York. When the firm’s founder retired, Shepherd bought the business and moved the rapidly growing enterprise into two new buildings on Pennsylvania Avenue.

By the time he was 30, Shepherd was making at least $75,000 a year — an incredible sum in those days — and he began to reach into other lines of business to make even more. He bought large tracts of land at low prices, subdividing them into lots for profitable sales. If potential buyers needed either loans or insurance, Shepherd arranged it through one of the companies of which he was a member of the board of directors. He was also deeply involved in planning and building Washington’s food markets. By 1870, Shepherd was the best-known real estate promoter and building contractor in the District, and his shrewd moves toward diversification of his business interests helped him accumulate a fortune of perhaps half-a-million dollars.

At the same time he was building a formidable business empire in Washington, Shepherd began to dabble in local politics. While still in his early 30s, he was elected to the City Council, and soon after that was chosen president of its upper branch. He had become an intimate of Ulysses Grant, who by then was ensconced in the White House. Through this political experience, coupled with Shepherd’s enormous and still-growing financial stake in the District’s future, emerged his plan for a grander scheme of things in the nation’s capital.

Shepherd and a small group of other leading Washingtonians began meeting frequently at night, trying to figure out how they could grasp the reins of power and bring the local government under some kind of home rule. They were distinctly worried that Congress might choose to move somewhere else, which would have brought ruin to the city’s economy and the fortunes of their businesses. The administration of District Mayor Sayles J. Bowen, which originally had been supported by the Evening Star and most of the Republican press in Washington, degenerated into bickering and backbiting. The New York Times had noted in 1870 that Pennsylvania Avenue remained “undrained, unpaved, and unswept,” and there was considerable public discomfiture with Bowen’s pledge to integrate Washington’s schools.

A drive to oust Mayor Bowen and replace him with Matthew J. Emery, a wealthy Washington businessman, was headed up by something called the Citizens Reform Association, and received the full blessing of the Evening Star. The chairman of the group was 35-year-old alderman Alexander Shepherd, who, along with four other prominent business leaders, had bought the Star in 1867. The association’s principal ammunition against Mayor Bowen was repeated allegations of corruption, but the group also played effectively upon the fears of wealthy Washingtonians that he was too “radical” on racial matters.

In Shepherd’s view, the ends justified the means, and his strategy for dumping Bowen and replacing him with Emery worked. Soon after, buoyed by their initial success in strong-arming the District’s election, Shepherd and other influential members of the Citizens Reform Association began lobbying Congress for a new territorial form of government for the District of Columbia. Shepherd and William W. Corcoran, the blueblooded bankroller, organized a series of steamboat cruises down the Potomac, cultivating congressmen — and their votes — with champagne and entertainment. The wining and dining paid off, and on February 21, 1871, Congress passed a bill uniting the District’s three governments (Washington City, Georgetown, and “The County”) and providing for a presidentially appointed governor, legislature, and board of public works.

One week later, President Ulysses Grant appointed Henry David Cooke as the first Governor of the District of Columbia, although it was widely believed Shepherd would be named to the position. Cooke was president of the First National Bank of Washington City (today’s National Bank of Washington, the nation’s oldest federally chartered bank); he also happened to be the brother of the infamous financier Jay Cooke, whose Philadelphia bank had largely financed the Lincoln government during the Civil War. From the outset, Henry Cooke was little more than a figurehead governor — Jay Cooke insisted that his brother’s new position not get in the way of more important business, namely the banking business. Jay Cooke, in fact, had pushed his brother for the job strictly because he thought it would add considerable prestige to the name of the family financial institution, particularly in Europe.

President Grant named Shepherd to be a member of the Board of Public Works a month later. Because the pressing mission of the new government was to begin long-overdue municipal improvements, it would be Shepherd’s stepping stone to Bossdom. At the board’s first meeting, he cleverly engineered his own appointment as its vice president and executive officer, even though the law authorized no such position. Cooke’s disinterest in civic administration had left a gaping void, and Shepherd moved quickly to fill it. Washington newspapers, led by Shepherd’s own Evening Star, jumped on Shepherd’s fast-moving bandwagon, and made it clear that he, and not Cooke, ran the new government. It soon became clear, in fact, that Shepherd was the new government. One editor coined a riddle that was soon picked up and repeated by wags, all over town: “Why is the new governor like a sheep? Because he is led by A. Shepherd.”

SHEPHERD’S QUICK CLIMB TO POWER was nothing short of remarkable. Other city bosses had slowly worked their way up through incumbent political machines, but Shepherd found himself — almost overnight — with an iron grip on the territorial legislature and on various city commissions. The mandate to launch a massive public-works program — and its attendant opportunities for graft — was his for the asking.

Shepherd soon realized, however, there was no way to pay for all of the improvements he wanted, so he appointed an advisory committee to make recommendations on desirable municipal improvement projects and the costs involved in completing them. With study in hand, he went to the legislature and asked for a $4 million loan (the balance of the total improvement budget of about $6 million was to be raised by taxing property owners whose real estate holdings would increase in value). But critics charged there was no way to pay back the loan and succeeded in holding up Shepherd’s plan in court. Shepherd reacted with the time-honored method used by all strongmen: He called new elections that not only would be a referendum on the loan proposal but would force every member of the territorial legislature to stand for re-election.

In the middle of the campaign, the court injunction against the $4 million loan was overturned, but the pro-Shepherd territorial leaders wanted the elections to proceed. They had every expectation of winning a vote of confidence, largely because they had arranged to import poor blacks by the boatload from the adjacent farms of Maryland and Virginia for voting purposes. On November 22, 1871, the Shepherd forces won an overwhelming victory.

In the face of lingering resentment over his unorthodox methods, Shepherd advertised for public-works bids, presumably on the theory that the Board of Public Works would award contracts to the lowest bidders. But when all the envelopes were opened, Shepherd summarily rejected the whole batch, claiming they were too low to insure quality work. (The real problem, of course, was that few of his friends and business partners had managed to submit the lowest bids.) Shepherd then established his own scale of prices for the work to be done, and simply awarded contracts to whomever he pleased — without even as much as preliminary estimates. One of Shepherd’s business associates, Lewis Clephane, submitted a bid for grading roadways at 20 cents per yard, and it was accepted. Some time later, Shepherd arbitrarily upped the contract to 30 cents per yard, and tossed in a bonus of a penny and a half for every 100 feet of dirt hauled away, effectively doubling the original contract. Instead of the standard three-year guarantee on the quality of a contractor’s work, Clephane was free to proclaim mea non culpa after only a single year. (Clephane eventually received more than $1 million in contracts from the territorial government.)

From the beginning, Shepherd did not seem reluctant to line his own pockets — as well as the pockets of his friends — from the proceeds of juicy municipal contracts. Even before the official beginning of the territorial government, he had begun spending money for regrading and other improvements along F Street, where he just happened to own fourteen houses. Throughout his term in office, dozens of companies in which he had major financial interests — including quarries, paving firms, railroads, markets, roofing companies, and newspapers — were awarded plum contracts. Shepherd, members of his family, and close business associates sat on the boards of — or controlled huge blocks of stock in — these companies, banks, insurance agencies, and real estate firms.

Shepherd was in a prime position to control the future direction of growth in Washington, and he did not seem to be reluctant to take advantage of his inside line on upcoming public-works improvements. Early on, he helped set up a real-estate pool known as the “California Syndicate” because it involved members of Congress from Western states. Shepherd’s wide-ranging real estate holdings included sizeable tracts in an area of the city that later became known as Dupont Circle. He built three mansions in the area — “Shepherd’s Row” — and it was well known that he intended to make large-scale improvements in the Northwest section of Washington. The real-estate syndicate, financed by Cooke’s bank, bought huge parcels of suburban land in Northwest, and as the growth of the city followed Shepherd’s improvement plans, so did their profits.

By any standard, it was corruption on a grand scale, but Shepherd did not let even petty opportunities for graft pass. John F. Seitz, a local baker, was awarded a contract for improvements to 10th Street, even though he had no intention of fulfilling the contract. He divided the money with M. Frank Kelley, a clerk in the assessor’s office, and Arthur Shepherd (the Boss’s brother). The conduit for laundering the money was another Shepherd crony, Louis S. Filbert. Filbert also was making handsome profits on other contracts, and ultimately was found to have been overpaid by more than $70,000 for contracts let to him.

Shepherd’s Board of Public Works also authorized a policy of contract extensions. A contractor named Daniel Hushnell, for example, was to be paid $753.58 for laying sidewalks along Pennsylvania Avenue. The contracts kept flowing Hushnell’s way — without estimates or bids — and when all was over, he had been paid more than $24,000 in extensions. The pickings in Boss Shepherd’s public-works bonanza were so enticing that even out-of-town firms got interested, including the Chicago-based DeGoyler-McClelland Company. The finn’s Washington lobbyist, one G.P. Chittendon, greased the wheels in Shepherd’s Washington with at least $50,000, trusting it would land in the pockets of those who might be able to help his paving company get plum contracts.

The scope of public-works improvements in the first year of Boss Shepherd’s reign, not to mention the cost, was enormous. More than 180 miles of new water mains were laid. Despite bad weather, one of two major sewer systems was completed by November 1872. Much of the Washington Canal was filled in, and the rest was narrowed with pine-plank seawalls. By the end of 1871, Washingtonians could see real progress in the re-grading and paving of Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Maine avenues. For the first time in memory, it seemed that something was actually being done about the deplorable condition of the nation’s capital. Boss Shepherd played his cards close to the vest, and in his high-stakes game of public improvements, few Washingtonians knew how much money already was in the pot.

NOT ALL WASHINGTONIANS, HOWEVER, WERE HAPPY with Shepherd’s steamrolling tactics and spendthrift attitudes, least of all the city’s wealthiest citizen — and Shepherd’s former supporter — William W. Corcoran. In constructing the Slash Run sewer, Shepherd’s crews made the mistake of damaging the Louise Home for elderly women, Corcoran’s favorite charity (it was named for his daughter). Soon after that, Corcoran decided to launch a campaign against Shepherd in the city’s newspapers. He quickly found out that none of them would sell him advertising space, since most had been bought off by Shepherd’s lavish advertising contracts. As a result, Corcoran started his own anti-Shepherd newspaper, the Daily Patriot, which hammered away incessantly at Washington’s boss. (The newspaper’s integrity, however, waned when it was disclosed that one of its covert financial backers was none other than New York’s William Marcy Tweed.)

At the beginning of 1872, Corcoran and hundreds of other Shepherd opponents petitioned Congress for a full-scale investigation of the territorial government. Shepherd had tried to ward off the investigation by erecting streetlights in the city’s high-crime areas and by asking residents of areas scheduled for improvements for recommendations on the type of work to be done (recommendations which, of course, were later ignored). And the Board of Public Works announced that it might not be such a bad idea after all to keep a complete record of its expenses, something it had not really bothered to do before.

The select House committee investigating Boss Shepherd did not prove to be a particularly aggressive watchdog. It was chaired by Connecticut’s H.H. Starkweather, one of Shepherd’s close friends and business partners. John H. Crane, chief counsel for the anti-Shepherd forces, marshalled a huge body of damning evidence, but it was blunted by the Boss’s behind-the-scenes work. During one heated session, Crane asked Shepherd if he had once suggested that opponents of the original $4 million loan should “git up and git.” “I don’t know if I did,” Shepherd replied. “It is a sensible remark.” Crane then asked Shepherd to explain his comment, and the Boss tersely said, “I am not an interpreter.”

Another one of Shepherd’s tactics to shift public scorn to his opponents was to leave torn-up streets in disrepair during the investigation. When outraged citizens complained, they were told that the anti-Shepherd forces, by prolonging the congressional investigation, were holding up work on the improvements. In the end, the House committee gave Shepherd and his Board of Public Works a gentle rap on the knuckles. First, it warned the territorial government not to push the District’s debt beyond $10 million (something Shepherd probably had done already) and advised it to limit its excessive newspaper advertising. (In one five-month period, the territorial government had funneled more than$140,000 to sympathetic newspapers, including, of course, the Evening Star. With so much in advertising revenues at stake, the Washington press could not be expected to be particularly critical when Boss Shepherd ran into trouble.)

Shepherd, armed with some sort of official vindication, returned to his task with a vengeance. Armies of engineers and laborers proceeded at cutting down elevations and filling up ravines in the process of regrading streets. Work was completed at such a furious pace that homeowners would return to find their houses perched in what seemed to be midair; others could virtually step from the second-story windows to the freshly paved streets outside. Members of Congress and other powerful Washingtonians were paid back for the damage to their property, but most other homeowners were given only apologies.

Shepherd’s adherence self-proclaimed “law of necessity” also led to a grand gesture of defiance that resulted in a restructuring of the city’s market system. When the walls of the Northern Liberties Market came tumbling down, Shepherd was quietly dining with a local judge at his country estate, Bleak House (named for Dickens’s novel, a favorite of his children). The market, infested with rats and without question the ugliest in the city, was the center of controversy between Shepherd and the stall owners, who had threatened to obtain a court injunction to prevent the market’s destruction.

That night, however, such an injunction would have been out of the question, because Shepherd had taken the precaution of inviting the only judge in town out to his country place. He then dispatched crews to warn stall owners to leave the rickety building, and they then attached ropes to its already crumbling walls and tore the entire place down. As they cleaned out the rubble, workers found the bodies of a young boy who had gone rat-hunting with his pet terrier and a butcher who had obstinately refused to leave his stall. During the ensuing uproar, some merchants petitioned President Grant for Shepherd’s ouster, but the Boss’s friend in the White House simply ignored them.

Shepherd then proceeded to implement his plan for a coordinated market system in the District, so that instead of two markets roughly in the same part of town, there were three, separated geographically. In all, it was a sensible plan, except for one minor detail that tended to cast some doubt on Shepherd’s civic benevolence: He happened to have a major financial interest in the newly rebuilt Central Market.

IRONICALLY, THE GREAT PANIC OF 1873 finally ushered Boss Shepherd in as the Governor of the District of Columbia. The financial pandemonium had been started by the collapse of Jay Cooke’s overextended Philadelphia Bank, and in short time the entire Cooke empire was in ruins. Henry Cooke was forced, more or less, to resign as governor, and Grant appointed Shepherd to take his place. But now that Shepherd finally had achieved the title, he was on the verge of losing the power.

The rumors about kickbacks, payoffs, and other forms of municipal corruption would not go away, and Congress decided once again to investigate Shepherd and his cronies — a group now commonly called the “Washington Ring.” Because the first investigation had been lambasted as a whitewash, this time Congress authorized a joint committee, with the Senators to be appointed by President Grant and the Representatives by Speaker of the House James G. Blaine. Good friends had gotten Shepherd out of tight spots before, of course, and both Grant and Blaine were in the Boss’s court.

When the joint committee got around to examining the books of the Board of Public Works, there wasn’t really much to examine: The financial records were in such sorry shape that it was virtually impossible to tell who had been paid, how much, and for what. In a mad rush to complete the investigation before Congress adjourned, the joint committee was reduced to offering a single — but devastating — finding: Shepherd’s Board of Public Works had spent at least $26 million, more than four times what Shepherd originally estimated was needed, and more than double the ceiling Congress had slapped on the territorial government just two years earlier.

The joint investigating committee then concluded that the experiment in self-government for the District of Columbia had been a failure, and recommended that virtually everything but the city’s Board of Health be abolished and placed under the management of the Army Corps of Engineers. In a single swipe, the entire territorial government was found guilty of gross financial mismanagement. But Shepherd and all other major city officials were let off the hook. In its last session, the territorial legislature passed only one piece of legislation: an act appropriating its own salaries.

During Boss Shepherd’s short-lived regime, the scope of Washington’s transformation was staggering: 120 miles of sewers, more than 150 miles of road improvements (including grading and paving), 208 miles of sidewalks, 30 miles of water mains, 39 miles of gas lines, 3½ million cubic yards of excavating, and more than 60,000 trees planted. But the graft was staggering, too: Many of those municipal amenities had to be replaced during the next several years because of shoddy workmanship and materials. And many of Washington’s taxpayers had almost been crushed financially by the huge burdens Shepherd had placed on their unwilling shoulders.

To this day, it’s not clear where most of the money went, but the seven members of the “Washington Ring” probably got most of it. Six of them, including Governor Cooke, had trouble concealing their identities — even with the fragmentary records left behind. Boss Shepherd was widely assumed to be the missing link, but members of the congressional investigating committee claimed they had no evidence directly linking him to the scandal (in modern parlance, “the smoking gun”), though his brother and business partner were clearly implicated.

As a result of Boss Shepherd’s blatant mismanagement of public funds and outrage in Washington and elsewhere over his excesses, Congress abolished the District’s territorial form of government and imposed a three-member Board of Commissioners upon the city as a provisional government. (Even though the arrangement was intended to be temporary, it lasted until 1974.) But Shepherd’s coziness with President Grant, in the end, was too much for Congress to stomach. When Grant nominated him to become a member of the new governing triumvirate, the Senate tabled the nomination by a lopsided 36-6 margin. While Shepherd blamed the “independent press” for that final humiliation, he had no recourse but to return to private life.

For six years, he continued to live in Washington, and was given to complaining that his government service had made him at least $200,000 poorer. But he surely was not hurting financially, for he kept his irons in the political fire by throwing extravagant parties for Republican officials. He even dabbled on the art market, leading many in Washington to question his claims of poverty.

So it came as a complete shock to Washington when, one day in 1876, Shepherd declared bankruptcy. It was not, by any stretch of the imagination, a run-of-the-mill bankruptcy, however: His cronies in the business and banking communities bailed Shepherd out by arranging for a moratorium on his debts and floating bonds in multiples of $100 to pay off his creditors.

The real reason for Boss Shepherd’s financial ruin, suggested the Baltimore Sun, was his last-gasp gamble on the presidential election of 1876. Because of his close ties to the Republican Party, and because he desperately needed a new friend in the White House (Grant had decided against running for a third term) Shepherd put huge sums of money behind Rutherford B. Hayes, the G.O.P. nominee. When it appeared that Democrat Samuel Tilden actually had won, Shepherd decided he had grossly overextended himself, and declared bankruptcy. (Ironically, Shepherd should have waited a few months — Tilden was denied his marginal victory at the polls by a special Republican-dominated electoral commission and Hayes was sworn in as president on March 4, 1877. The independent press of the day called it the “Stolen Election.”)

But Shepherd’s fall from grace wasn’t quite finished yet. There were recurring rumors all through Washington that criminal proceedings might be started against him again, or that yet another congressional investigation might be launched, so in May 1880, Shepherd and his wife left for Mexico. Shepherd had somehow become interested in managing silver mines there, and had zeroed in on the mineral district of Batopilas, a remote river valley in the mountains in the southwest of the Mexican state of Chihuahua. He raised enough money to buy out William G. Fargo (of Wells, Fargo & Company) and organized the Consolidated Batopilas Mining Company with $3 million in capital. Shepherd’s genius at mammoth public works projects was ideally suited for a mining enterprise, and in a few years he had become a millionaire.

An underlying reason for Shepherd’s swift departure from Washington might have been that at the time, it was nearly impossible to extradite a fugitive from Mexico. Once there, he became friends with Mexican President Porfirio Diaz, then at the beginning of a long and ruthless reign of power.

By 1888, Alexander Shepherd was back in the saddle again financially, but the vagaries of fortune were soon to favor him politically as well. Time can be a healer, and the city from which Shepherd had been hounded only eight years before sent word that all was forgiven.

Though Boss Shepherd had fled Washington to escape ridicule and destitution, he was welcomed back to the nation’s capital with open arms and effusive forgiveness. The city’s upper-crust denizens had arranged a homecoming celebration as some sort of cathartic celebration for the man who had lifted the nation’s capital out of the muck and suffocated a drive to have it replanted somewhere near St. Louis. No mention was made of corruption, crookedness, kickbacks, and the like. The city fathers dispatched a distinguished delegation to meet him at the railway station, and he was escorted to the Willard Hotel amidst cheers and a marching band led by John Philip Sousa. There, after listening to addresses overflowing with praise for his achievements of nearly two decades earlier, Shepherd spoke to an applauding multitude. After his speech was over, Shepherd shook nearly 7,000 hands.

After years of not having Boss Shepherd to kick around any more, official Washington had staged an incredible orgy of recantation.

After a brief visit to New York, Shepherd returned to Mexico, where he died from a ruptured appendix in 1902. His body was brought back to Washington and in a solemn, pretentious funeral, laid to rest in a huge stone mausoleum in Rock Creek Cemetery.

IN 1909, A BRONZE STATUTE OF SHEPHERD WAS UNVEILED on Pennsylvania Avenue in front of the District Building. His figure was attired in a morning coat, his left hand held a partially unrolled map of Washington, and his right hand was thrust behind his back with the palm open. Critics of the monument suggested, with mock sincerity, that the Boss’s posture at least was correct. Shepherd’s friends said the likeness was unkind, that it did no justice to the man who raised Washington from the mud.

Today, however, such disagreements over the artistic merits of Boss Shepherd’s bronze statue might seem academic. The statue, a victim of downtown renewal, lies overgrown with weeds in a storage yard not far from the District’s Blue Plains sewage treatment plant in Southeast Washington. For now, at least, Boss Shepherd has been retired to a setting not unlike the Washington of the 1860s.

Fifty years ago, when Pennsylvania Avenue near 14th Street was being ripped up for another of Washington’s perennial redevelopment projects, Shepherd’s statue was among the landmarks scheduled for removal. A writer for the American Mercury, probably the most irreverent magazine in the nation, suggested it was not a fitting fate for Alexander Shepherd. The words seem as appropriate for today as they were then:

“So it will be a shame and a scandal if his bronze effigy is taken down and hidden away or melted up and cast into souvenirs. It should rather be carried up the Avenue at the end of another triumphant procession, and there permanently set up at the foot of Capitol Hill.

“There let him stand, a grim, ironic, truly American figure, looking down over the city which he looted — and saved!”

Sidebar: Brinksmanship, Shepherd Style

This article originally appeared in the November/December 1981 issue of Regardie’s.