Patently Inventive

IF PAUL SPLITTORFF GETS SMART and teams up with George H. Playter, Jr., the Kansas City Royals just might have themselves a Cy Young Award winner next season.

No, George Playter is not a promising catcher in the Royals’ farm system, nor is he the pitching coach who taught Fernando Valenzuela the screwball. In fact, George Playter isn’t in the record books, and his name undoubtedly has managed to slip by even the most dedicated aficionados of sports trivia. But he just may have baseball’s best secret weapon since the accidental discovery of that horsehide-resistant concoction in “It Happens Every Spring.”

So who is George Playter? Like a surprisingly large number of Kansas Citians, he’s an inventor. But while others have been spending their time on the sorts of ideas one usually associates with inventors — an electrical communications system or a sedimentation device for purifying waste water, both of which had recent Kansas City roots — George Playter has patented an idea designed to keep pitchers firmly anchored in the starting rotation. His device would allow pitchers to work out without a human catcher, while still being able to judge the accuracy of their throws.

Playter, however, isn’t the only area inventor with sports on his mind. In the last few years, Kansas City residents have been awarded patents for such items as a racket-mounted tennis ball retriever, a fishing rod holder, and, for those baseball fans forever losing beers to errant foul balls, a tray that grips the arm of a stadium seat.

The city’s great minds have kept themselves busy with a wide range of newfangled, non-sports ideas, too: everything from chemical, electrical, and scientific discoveries to household-type items that may one day be standard equipment on kitchen counters.

Actually, inventing is nothing new to Kansas City and its environs. While some parts of the nation have been conspicuously short on innovation, the flow of new ideas from this area has, over the years, remained strong and steady. Inventors in some areas have to travel out of state to find a patent attorney; Kansas City has more than its fair share, and there’s plenty of work to go around.

Not all of the new ideas are potential Hula-Hoops, though. In fact, some of these brainstorms might make you happy you’re not in any way related to the proud inventor.

A good number of the inventions patented during the last few years by Kansas City residents have been for purely industrial applications — the kind of products the general public will never see, and probably wouldn’t appreciate anyway: the “Liner for Concrete Forms.” for example, and the “Method of Degerminating a Kernel of Grain by Simultaneously Compressing the Edges of the Kernel.” There is the “Process for the Reclamation of Acid from Spent Pickle Liquor,” a “High-Speed Television Camera Control System,” and, for chicken lovers, an interesting duo: a “Sealed Feather Picking Unit” and a “Method and Apparatus for Eviscerating Poultry.”

Other non-industrial innovations concocted locally include a spectacles frame with snap-in lenses, a method for attaching a hairpiece, and a convertible purse that can be used as a tote bag, knapsack, handbag, or clutch purse. Kansas City inventors have come up with everything from a new type of nozzle on a swine-feeding machine to a new kind of lock and an easy-open envelope. There’s even been a new type of internal combustion engine.

But why do they do it? Why do some residents spend their time perfecting products that the rest of the world may deem utterly useless? In most cases it’s for financial gain — a chance to pan for gold and strike it rich. But that is just part of the reason, and it doesn’t fully explain who these people are or the sources of their inspiration.

FIFTY YEARS AGO, KANSAS CITY BUSINESSMAN C.A. Sherman ran a type of clearinghouse for patents and inventions, where new ideas were refined, developed, and marketed. Among the brainstorms that found their way to Sherman’s desk were football-shaped water wings that supposedly made it possible to walk on water, a bit for drilling square holes, and an urn that perked coffee with a jet of steam. And then there was the memorable — if thoroughly impractical — vessel developed by a lumberjack, which Sherman described to the Kansas City Star in the 1930s.

“He had a great idea.” Sherman was quoted as saying. “He had invented a cigar-shaped canoe with which one could jump over waterfalls and not be injured. At least, he thought so, although he had never tried it. He wrote us asking about the possibilities of patenting it.

“I replied that it would be foolish to patent it because there weren’t thousands of people in this country dying to take a leap over waterfalls, anyway. He might sell four or five, but that would be all. I then asked him how he knew it would work. Do you know, when he received that letter he went out and tried it! He’s been jumping waterfalls ever since.”

Local inventors have, for the most part, been working on tamer ideas lately, although patenting even the most practical new product still requires a dangerous leap. The average waiting time to receive a patent is now two years, and a would-be Edison can count on spending $1,200 or so on legal, search, and filing fees. And once the patent is in hand, there is the not-insignificant matter of competition: at last count, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, just outside of Washington in Crystal City, Virginia, had granted patents for nearly 4.3 million inventions, with about 70,000 new ideas approved annually. It’s tough to beat the house with those sort of odds, but Kansas City inventors continue to roll the dice.

Paul Yust, a Kansas City cabinetmaker, is a prime example. Last April, he received a patent fora device officially identified by the Patent Office as a “Stadium Seat Arm Gripping Tray.” In essence, Yust’s invention is a plastic tray (the original model had been a heavier wooden version) that slides easily onto the arm of a stadium or theater seat, providing a convenient place to rest food and drinks. Because most sports stadiums have the same type of seats, the device has national marketing possibilities. And where seats are different, an insert makes the tray easily adaptable.

Like a lot of inventors, Yust’s idea came from personal experience. “I was always kicking my beer over in the stadium,” he says. And like nearly all inventors, he has found that getting a new idea patented is the easy part; successfully marketing the invention poses the real challenge.

The problem. Yust says, is money. He can’t afford to go out on a limb with his three-inch-wide holder, which he predicts will retail for about $5, and so far he hasn’t signed a deal with a major manufacturer or distributor. There has been some interest, and one company has been taking a closer look, but for the moment it’s a tough waiting game.

Ted Herbold is also waiting for the big score, but the inventor of the “Tilt-A-Body Stretch Lounge,” a souped-up slant board designed to offer relief for everything from leg cramps and a bad back to chronic stress and bronchial conditions, has taken a different route. He assembled a group of investors about three years ago, and together they formed Innovated Products Corporation. The firm manufactures the 78-pound stretch lounge, which Herbold says took more than a decade to perfect through a number of major modifications. In its first year of sales, Innovated Products has sold its lounge in 12 states, and Herbold, a retired accountant who serves as company president, believes there’s a waiting market of chiropractors and corporate executives to buy it. The problem, simply, is reaching them.

LIKE MOST INVENTORS, WHOSE ENTHUSIASM invariably is contagious, Yust and Herbold believe it’s merely a matter of time before their inventions find a profitable niche in the marketplace. If their optimism proves unfounded, though, they at least will be able to take solace in the fact that they’re in good company.

Inventors, for the most part, are a persistent bunch who are convinced they know a good thing when they see it. If something doesn’t pan out, they happily turn back to the drawing board to fine-tune the failed product or prepare rough drafts of a new one. Tunnel vision is a common affliction among inventors, who rarely, if ever, see anything but runaway success surrounding their idea. Their visions, unfortunately, rarely prove more than a mirage. “Inventors are notorious for not being objective about their inventions,” says John Liu, a suburban Philadelphia businessman who serves as president of the American Society of Inventors. “It’s like their baby. They just can’t conceive of the idea that what they’ve invented is worthless, or not worth as much as they think.

“I know many inventors who have poured their life savings into their inventions, only to have finally realized — some of them still don’t realize — that, ‘Hey, this is not going to get me anything.’ And the saddest cases are those who work literally years on some invention, spend their money on it, and then have a market research firm tell them — if it does the job honestly — ‘Look, forget it. This will never pay off.’ “

The key question, of course, is determining what will pay off. No one knows in advance, but the most successful inventions, historically, have been the industrial items for which a specific, ready market often is available.

One of the few Kansas City residents who has made his living inventing in the industrial arena is George Dean, chairman of the board of Dean Research Corporation For the last 42 years, Dean has been focusing his attention of the development of new products, primarily in the aeronautical field. And one new idea Dean’s company has been working on may soon bring smiles to the nation’s airline passengers.

The invention is a variable-speed walkway that accelerates once passengers are on and then decelerates for easy exit. The U.S. Department of Transportation, along with the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey and the Urban Mass Transit Administration, set up a project to evaluate various concepts of accelerating walkways, and Dean Research was one of the companies selected to develop a prototype. The technology is still in the embryonic stage, Dean says, and although his firm has a 60-foot-long working model, it probably will be two to four years before airline terminals have the movable walkways, which will be able to speed passengers at 500-700 feet a minute — five times the rate of a constant-speed walkway.

As a result of a cutback in transportation department funds, Dean says, the future of the walkways may be in jeopardy, but even without this project the company will have enough to keep it busy. Dean estimates his corporation has about 50 patents to its credit, and its projects, unlike those of the typical independent inventor, are really no-risk propositions.

Dr. William J. Bell, professor of entomology at the University of Kansas at Lawrence, also took government money and put it to good use. For the last six years, Bell has been studying the basic biology of the cockroach with funds from the National Science Foundation. Using a synthetic substance that duplicates the odor secreted by female cockroaches to attract males, Bell came up with a new trap that lures the bugs onto a sticky surface, from which there is no escape. Field tests have proved successful, and Bell believes his traps will mean the end of the line for a lot of household pests. “I’m not sure which company will pick up this idea and transfer the technology to the public,” Bell says. “But it’s going to happen.”

SOME PATENT LAWYERS BELIEVE that the independent inventor may one day — perhaps quite soon — be a fond reminiscence. The nation’s major corporations pay close attention to the goings-on at the Patent Office, where block-long, seven-foot-high stacks of printed patent drawings chronicle the great and not-so-great moments in American ingenuity. It is here where a high-priced battery of corporate lawyers, well-versed in patent-law loopholes, can give their clients a leg up on an independent inventor. The laws are just vague enough to allow a product with commercial potential to be copied — although with minor modifications – meaning a potential mass-market success for a resourceful company and no rewards for the “little guy.”

Still, the independent inventors, apparently unaware of their predicted demise, press on, and often without the knowledge of family or friends, who just might not understand why time isn’t being spent on more “normal” endeavors.

John Morman is probably typical. In 1980, Morman, after being rejected once, was granted a patent for a “Body-Mounted Umbrella.” It took more than two years for the paperwork to be completed, and it cost Morman, a Kansas Citian who describes himself as “just a working man,” about $1,200 altogether.

Morman’s invention is simple enough: the umbrella is attached to a pole that straps around the waist; a switch activates the mechanism to unfold the umbrella, leaving someone free to carry home both bags of groceries in the rain. The inspiration for this idea was a bit different, however: “I fish a lot and I see people out in boats in the hot sun,” Morman says. “I said to myself that if they had an umbrella that strapped on, they’d have the use of both hands.”

Morman’s invention may not be the most orthodox, but he says those who have seen his prototype (which he wears around town) like the idea and invariably ask where they can buy one.

They can’t, and won’t be able to unless Morman can find someone to manufacture and market his invention. The cost of producing a new item — any item — usually is too expensive for independent inventors, and even if production costs are met, the marketing hurdle can be nearly insurmountable.

One small local company that seems to have one leg over the hurdle, however, is the Tele-Stat Corporation, which was formed to promote an invention patented by James Perry. Perry, who has been in the heating and air conditioning trade for 18 years, is owner of Air Technology in Kansas City. What Jim Perry came up with is an apparatus that uses a standard telephone to control a thermostat. With an energy-conscious country, Perry and Tele-Stat may be onto something.

The invention is designed especially for hotels and motels, as it allows someone at the main desk to automatically control the temperature of unoccupied rooms. The device is not very expensive to install, Perry says, particularly when energy and tax savings are taken into account. Any temperature can be ordered up by the front desk, insuring that fuel and electricity are not needlessly spent heating or cooling an empty room.

Tele-Stat has approached a number of large motel chains, and Perry thinks it’s only a matter of time before his company succeeds. But it may be a long time, Perry admits, because money is tight and people are not eager to make capital investments. “It’s a tough process,” he says. “But we think we’ll do OK.”

George Playter also thinks he may do well, although he hasn’t yet really gone looking for a manufacturer. In any case, the Royals bullpen might want to take heed.

Undoubtedly, one of the hardest parts of learning to pitch is not throwing the off-speed stuff or holding a runner close to first, but finding someone to sit still and catch your pitches. Even if you can convince a friend into giving up his Saturdays for an off-season workout, it’s often hard to tell without a batter whether your pitches are finding their way into the strike zone.

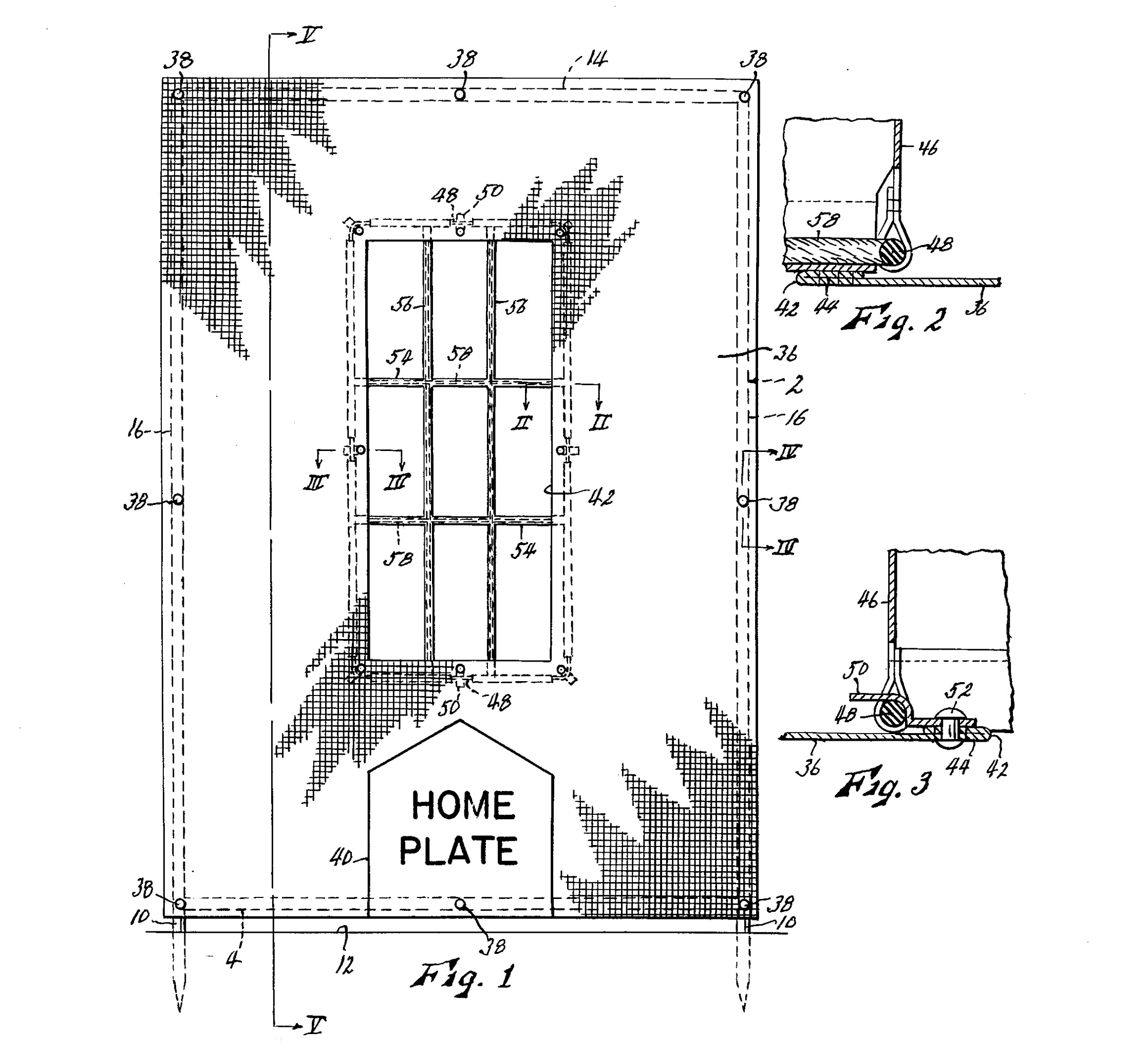

After giving all this some thought, George Playter came up with an idea that makes tolerant friends expendable. Playter’s “Pitching Practice Device,” the first invention for which he’s received a patent, falls neatly into the why-didn’t-I-think-of-that category. Basically, it’s nothing more than a canvas sheet, supported by a tubular frame anchored in the ground, that conforms to the size of the strike zone. The sheet has nine openings with canvas chutes — something like a billiard table. A pitcher working on a fastball low and away need only throw (never aim, the masters say) toward the appropriate opening. After throwing a series of pitches, he then checks to see in which pouches the balls landed.

Playter, who says the idea just came to him one day while watching someone pitch, plans on approaching sporting-goods manufacturers in hopes of marketing his idea. And for those who worry that throwing at a piece of canvas won’t give a pitcher the proper perspective, Playter already has that problem solved: it’s possible, he says, to add the figures of a batter and umpire to the canvas.

Whether Playter’s brainstorm will ever find a national audience is uncertain, but if the Royals ever give it a test, local baseball fans could spend Saturday afternoons next season watching a Cy Young winner with untouchable, pinpoint accuracy. Or, if the device proves ineffective, they could pass the time lunging recklessly for foul balls and home runs, secure in the knowledge that their beers are anchored firmly in a tray on their stadium seat, as one Kansas City inventor, another face in the crowd, smiles broadly over the merger of the American Pastime and the American Dream.

Sidebar: A Portfolio of Kansas City Inventors

Sidebar: Caveat Inventor

This article, by Alan Green and Bill Hogan, originally appeared in the December 1981 issue of Kansas City magazine.