Build a Better Mousetrap

ISAAC MENDELOVICH KNOWS WELL THE ROAD from center city to Crystal City — a three-hour trek southward to a place just outside of Washington where modern-day prospectors, squinting at computer terminals, spend their days digging for the mother lode. But in Crystal City, where block-long, seven-foot-high stacks of documents chronicle past finds and near misses, there is an ironic twist: it’s not what you discover there that might make you rich: it’s what you don’t find.

Crystal City, Virginia, is the home of the U.S. Department of Commerce’s Patent and Trademark Office, where nearly 4.3 million new ideas have been registered since it was first established by President George Washington in 1790. This is the repository of telephones and hula-hoops, of the million-dollar moments in the annals of American ingenuity: the hall of record for the likes of Edison and Eastman, Goodyear and Goddard — and the place where Isaac Mendelovich, 32-year-old vice president of marketing for a small Philadelphia industrial firm, can, with a little luck, parlay an untried idea into a financial killing.

Mendelovich is in good company. Philadelphia’s first famous inventor was Benjamin Franklin, who invented the lightning rod in 1749 and followed with such innovations as a copperplate press for printing money, a mangle for pressing linen, bifocals, and a clock that showed hours, minutes, and seconds on three revolving wheels. Other Philadelphians have followed Franklin’s lead with patents for everything from the blowpipe to the steam shovel to the first multi-color printing press — and the accordion, the letter box and the cable car; the revolving door, the reclining chair and the pencil with attached eraser. True, there have been wide gaps between success stones, but not too wide to keep Philadelphia inventors from persisting, adding their names to the roster of what has evolved into a peculiar subculture, complete with its own clubs, newsletters, conventions, and scams. Most recent inventions here, as in other cities, have industrial applications: the chemical, scientific, electrical or mechanical gizmos rarely seen, and never appreciated, by the general public.

But there are the consumer items as well — the games and toys, appliances and furniture, holders and heaters, protectors and projectors — the kind of products that one day may sit unobtrusively in living rooms and on kitchen counters all across America. Some are inventions you wish you’d thought of first: others are gadgets with which you may be happy not to be associated.

In short, inventors here and everywhere have conceived of everything from the practical to the practically useless, emerging from their basements and work-shops—often without the knowledge of friends or family — with drawings or models of the device that someday may earn them a footnote in the history books.

For instance:

On April 15, 1980, 20 months after the papers had been filed, David Gutman received a patent for a device officially identified by the Patent Office only as a shovel. Shovels, of course, are nothing new, but Gutman’s shovel had some new twists: two fulcrum-type levers that allow even the less-than-able-bodied, with minimal effort, to keep their sidewalks free of snow. The ideal item, Gutman thought — so ideal that he paid City Hall $60 for a vendor’s permit and put up a little streetside stand to sell his new invention.

The improved shovel (in Patent Office parlance, almost everything is an improvement of something else) is Gutman’s fifth patent. His first, an automobile bumper that protects pedestrians from injury, was awarded in 1972. Soon after that patent was issued, Gutman says, the letters from General Motors started arriving, asking if he’d come out to Detroit to discuss the prospects for his invention, But there was no talk of money, and Gut-man, who couldn’t afford the travel expenses out of his lone income — Social Security payments — never did go west.

By the time Gutman took to the streets with his shovel, his sixth invention — a variable-speed fire escape — was already in the works, and Gutman, who had invested 80 percent of his $1,500 savings into patenting the shovel, was counting on sales of the back-saving device to help finance the completion of his latest venture. Inventing had become important to Gutman: with virtually no tools and little money, he headed for his South Philly cellar each morning to refine his latest ideas, sending out pieces to machine shops, looking for the right designs, waiting for the big score. And if Gutrnan was mystified by his lack of success, his friends, who had watched the development of seemingly salable items, also wondered when the work would finally reap some rewards.

“I need some help, I think,” Gutman says. “Or maybe I’m a poor businessman. Everybody says. ‘With all your inventions, and all the newspaper write-ups, why don’t you make more money?’ Well, I’m working without capital. I only get $350 a month from Social Security.”

But with the shovel, which also had received good advance notices from friends, Gutman thought he finally had a winner. There was just one unforeseen problem, however — one overlooked, dream-deferring variable, which Gutman relates a bit dejectedly: “We didn’t have any snow last winter. So I didn’t sell too many. I did make some clear profits. but the machine shop, the patent, the lawyers — that’s a lot of money.”

Gutman’s bad luck, of course, hardly was cause to give up the daily jaunts to the basement. Most inventors, no matter how poorly their brainchild may fare in the marketplace, invariably have another idea or two up their sleeves. Inventors, for the most part, are a curious and persistent breed: even in the midst of failure, with the brass ring little more than a mirage, many begin again the long, arduous, expensive process. It is an odd blend of masochism and determination — a myopic subculture nurtured on fizzles and flops, where tunnel vision is 20/20 eyesight and one-shot deals are nearly nonexistent. And given the failure-to-success ratio, most had better be constantly working on a sequel if they hope to make some money.

AS GET-RICH-QUICK SCHEMES GO, INVENTING is undoubtedly one of the worst. Very few inventors ever get rich; even fewer find fortune quickly. But like those who methodically seek the perfect triple combination in thoroughbred racing, plenty of amateur inventors believe the big payoff may be just around the bend. Both inventors and horseplayers are willing to accept the risks, both believe in the eventual triumph, and both yearn for a sizable dose of luck now and then. And just as most horseplayers leave the track with less money, most amateur inventors are never able to recoup their investment with a winning ticket.

That’s because getting an idea patented is the easy part. Nearly two-thirds of all patent applications are approved. It’s marketing the product that presents the real challenge, and that’s where the dream usually evaporates.

John Liu, vice president of Philadelphia Gear Corporation in King of Prussia and president of the American Society of Inventors, says it’s rare — perhaps a one in a thousand chance — that an inventor gets rich from an idea. The most frequent malady that afflicts inventors, he believes, is falling in love with their creations, at which point the blinders get soldered to the cheekbones. “Inventors are notorious for not being objective about their inventions,” Liu says. “It’s like their baby. They just can’t conceive of the idea that what they’ve invented is worthless, or not worth as much as they think.

“I know many inventors who have poured their life savings into their inventions, only to have finally realized — some of them still don’t realize — that, ‘Hey, this is not going to get me anything.’ And the saddest cases are of those who literally work years on some invention, spend their money on it, and then have a market-research firm tell them — if it does its job honestly — ‘Look, forget it. This will never pay off.’ “

The sheer odds, however, rarely appear to be an effective deterrent, because nobody can predict what’s going to sell. Of the 200 or so patents awarded to Philadelphia inventors each year, for example, the list includes these recent labors of love: a psychotherapeutic card game designed to measure a player’s maturity: an apparatus for supporting hand-held hair dryers; a digital pulse generator for producing a hypnotic effect, ideally suited for biofeedback; a retractable dog leash, which rolls up like a tape measure; a game board adaptable for a number of word games on the order of Scrabble and crossword puzzles; a device designed to prevent intruders from tampering with door or window locks; and an adjustable-size toilet seat adaptable for small children. And then there’s Silverio Hernandez’ prosthetic spur for fighting cocks, assigned to Conquest Manufacturing Company in Philadelphia.

But even if an idea looks promising, with success a possibility, the patent laws are just vague enough to make it possible for independent inventors, without vast resources for legal assistance, to have their ideas stolen. A minor modification theoretically makes an invention a completely new product. often leaving its original creator unable to reap the rewards of his labor.

Peter Bressler, a center-city industrial designer, knows all about this. When Bressler graduated from college, he scraped together — with the help of his family and friends — $50,000 for the development of a spring-assisted wheelchair that would allow paraplegics to sit down and stand up unassisted. Bressler recouped $30,000 on licensing fees, but ultimately took back the rights because he didn’t like the way the product was being handled.

The real prospects for financial gain, though, might have come from overseas. Bressler’s wheelchair, the first of its type on the market, was warmly received by a Swiss gentleman, who planned to solicit the rights to the device for all of Europe. Again, Bressler’s hopes were dashed when his European contact suddenly withdrew from the deal. Three years later, Bressler saw his wheelchair — with a slightly modified spring — at a rehabilitation conference. The patent holder of this revolutionary idea just happened to be a certain Swiss.

Bressler not only shrugged off his bad fortune and the loophole in the law that made it possible, but jumped into the inventing business with both feet. Twelve years ago, still heavily in debt from the wheelchair experience, he founded his own consulting firm, Peter Bressler Design Associates. As an industrial designer, Bressler handles products from the design phase to the packaging and graphics. He has a number of patents to his credit, some of which he did under contract, meaning he no longer retains the rights. But he also has a second patent on his own — the type of item you’d swear just couldn’t miss.

Bressler’s idea, patented in May 1981, is proof that necessity is indeed the mother of invention. Every morning, when Bressler left for work, he hit the street to find that his Fiat, which had old tires, invariably had a flat. If he just had a way to fill the tire enough to travel the six blocks to the nearest service station, Bressler thought, his worries would be over.

So he invented a flexible hose that transfers air from an inflated tire to a deflated tire. The bonus is that it’s fitted with a check valve that automatically cuts off the flow from the inflated tire when the pressure falls below a predetermined level.

It works — but whether the device ever will find its way into the marketplace is another story. One major bicycle company has taken an interest; a national department-store chain took a close look before backing off. Bressler remains optimistic — but realistic. He’s been through this before. And if his tire inflator does become a big item, Bressler will be one of the few Philadelphia inventors to crack the consumer market. Thus far, the real success stories have been in industrial arenas.

ONE OF PHILADELPHIA’S MOST PROMINENT INVENTORS is Frank Piasecki, who dreamed up the banana-shaped helicopter with rotors on each end, used extensively by the Marine Corps and the Navy. Piasecki’s invention paid off in a big way when he sold his company to Boeing, took the earnings, and formed Piasecki Aircraft Corporation, which is carrying on the tradition.

Joining Piasecki in the ranks of the upper echelon is Frank Patnall, who invented something called the strain gauge. Patnall, now in his 90s, has other inventions to his credit, but it is the strain gauge, which measures stresses and strains, that gained him worldwide recognition. His invention proved so successful that it spawned a book, Patnall on Testing, which chronicles how he came to dream up the idea.

Piaseclti and Patnall, however, are exceptions. Twenty-five or thirty years ago, Philadelphia had a good number of major manufacturing firms, potential nearby outlets for industrial innovations. But many of those companies, such as Philco, are long gone, necessitating long-distance relationships for inventors in search of a market.

Even with decreasing opportunities, though, the patent industry in Philadelphia still thrives. Zachary T. Wobensmith II, president of the Philadelphia Patent Law Association, estimates there are 200 members on the group’s roster, spread throughout Delaware, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. (By comparison, the entire state of Arkansas, which did not have a single patent attorney until 1972, now has four.) But Wobensmith, who has been practicing patent law for nearly 50 years, seems to think that the independent inventor may be going the way of the buffalo. “The casual inventor is a somewhat vanishing species,” he says, “although he hasn’t vanished yet.”

Actually, the garage and basement tinkerers, if declining, still seem determined to stay in the picture, because it frequently is an inventor’s own interests and experiences — à la Mr. Bressler’s uncooperative tires — that serve as inspiration for another patent being added to the pile.

Witness Ronald Keeley. What started out as a Little League coaching stint ended with the “Portable Sports Equipment Organizer.” If the nation’s coaches follow Keeley’s lead, gone will be the days of overstuffed duffel bags lying beside the dugout. A machinist by trade, Keeley concocted a baseball-equipment attaché case that flips open to hang easily on the playground fence. For about $50 a pop — a number of Philadelphia playgrounds have hopped on the bandwagon — it’s possible to keep an eye on all the bats and balls.

Anthony Taff fits the same mold. The “Taff Staff” is the work of the man who was the original trainer for the Philadelphia K-9 Corps. Essentially, the Taff Staff is a cane with a dog leash attached via a coil spring, which gives the dog a good rap in the ribs when he misbehaves. It’s all humane, but it does let the animal know in no uncertain terms exactly who’s master.

Taff’s son, Anthony Taff, Jr., is handling sales of the product out of an Upper Darby office. A few hundred have been sold, but Taff, like most of his cohorts with an invention, believes that the proper publicity will give the company’s books a rich shade of black ink. “I’d like to go national with this thing, but unfortunately, I haven’t been able to get the attention that I think the product surely deserves. My father has high hopes for the Taff Staff. He believes that this is a multimillion-dollar invention if he ever heard of one.”

Ernest Schiff, who, with a partner, has patented a skylight fire-escape system, echoes that familiar refrain: “It has a lot of possibilities, and with the proper promotion and advertising . . .”

Good ideas, one and all, with the common denominator being insufficient capital to inform the world. In Schiff’s case, the inspiration came after two students of the middle-school teacher died in a fire. The Philadelphia Fire Department thinks it’s a great idea, Schiff says, because it provides quick and easy escape from a burning building. But the marketing money isn’t there, and Schiff’s Lifeway Corporation, which has sold about a hundred of the units, is looking for business by blanketing Philadelphia neighborhoods with promotional leaflets.

The real question, of course, is how inventors are supposed to know whether their idea really is a winner, rather than something they’ve merely fallen in love with. “I happen to be an inventor at heart, but I normally invent to fill a need,” says John Liu. “Obviously, it’s much easier to sell an invention that fills a need than to invent something and then go find out who needs it.

That’s exactly how Don Newman met with success early on. While a student at Penn State in the early ’60s, he developed a moving piece of playground equipment that simultaneously requires group cooperation to keep it in motion and hones the balance and coordination of the individual participants. Based on his belief there was a definite market for his maintenance-free tumble gym, he raised the money to rent a warehouse and manufacture it himself. A local private school commissioned the prototype; seven more were made and sold. The feedback was unanimously positive. He peddled the patent to a national manufacturer of playground equipment and now nets $10,000 a year.

Newman found making his own inventions such a good idea that he went on to self-produce his next hot item, the Newman Roller Frame. It’s a revolutionary, self-tensioning, lightweight device used in screen printing, which he sells to graphic arts and design outfits as well as to industries that print on their products. Between sales of the inventions that he makes and licenses of his patents, he’s grossing six figures. Not bad for tinkering.

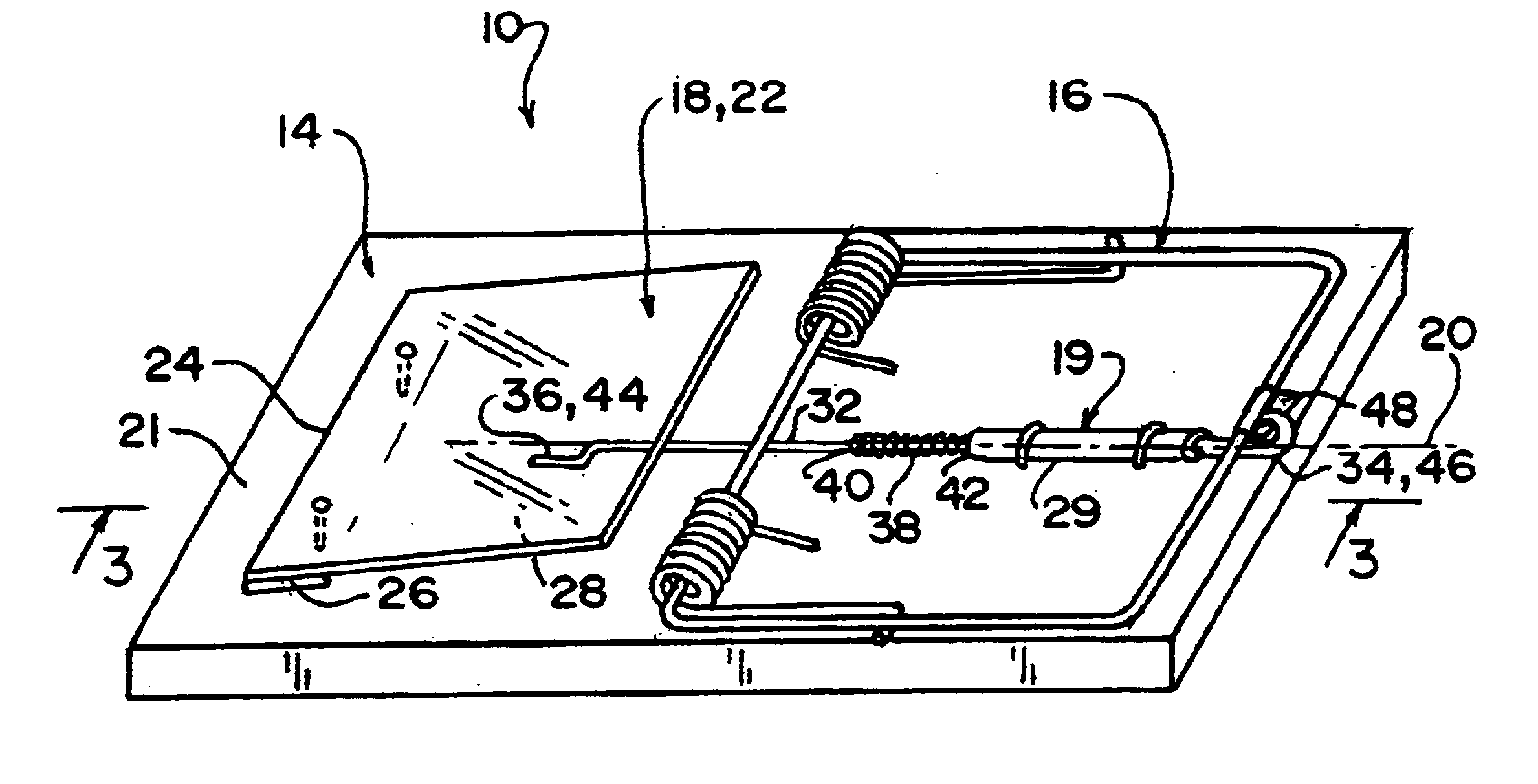

Jacob Labe III, an industrial designer from Elkins Park, is another rare one who makes his living strictly from his own creativity. With more than 30 years experience in the field, Labe is always working on new products — both on assignment and for his own ventures. Throughout the years, he has seen few significant success stories, and the pattern in other cases almost always is the same. “They think they’ve got the brass ring, they’ve got the new mousetrap, and most of them make one major, serious mistake — and that is not evaluating the marketplace before they spend the money.” In fact, at clinics for would-be inventors, Labe tells about half of them to drop the project entirely.

And, Labe cautions, “The minute you have a patent and it becomes public knowledge, every butcher in the country goes after you.”

INVENTORS ACROSS THE NATION HAVE DISCOVERED that they suddenly become more popular after they are awarded a patent. It’s not so much that friends admire their ingenuity and relatives offer their congratulations — it’s that inventors become the targets of firms looking for a fast buck. Some companies peddle memorabilia of one kind or another, like a 10-by-14-inch plaque mounted on a walnut base ($60), or an article from a periodical about the inventor’s patent ($4.95 and a stamped return envelope). The “article” turns out to be not from The New York Times, Wall Street Journal, or Scientific American, but from the Official Gazette of the U.S. Patent Office.

Philadelphia inventors say they also find an avalanche of mail from companies offering assistance of some sort: evaluation, advertising, research and development, marketing, promotion, engineering, manufacturing, and sales. “There are some unscrupulous firms which list themselves as aiding the inventor,” says Liu. “They want a lot of money for almost nothing.”

One nationwide firm investigated by the Federal Trade Commission, the Raymond Lee Organization Inc., disclosed that of the approximately 30,000 inventors it had assisted, only three received more money as a result of the company’s services than they paid in fees. The FTC said the firm and one other like it provided “worthless services that bear little resemblance to what they tout in their advertising, promotional, and sales pitches.”

But despite the long odds and formidable obstacles, inventors are a persistent lot, searching for vindication in a fickle marketplace. Isaac Mendelovich, for one, is convinced that that marketplace has a niche for his product, and he’s fully prepared for the battle.

Some years ago, in the middle of completing his master’s degree in business administration at Temple University, Mendelovich had an assignment in a creativity course that got him started on the pathway to a patent. A friend of his was missing a hand, and was forever having trouble with toothpaste tubes. Mendelovich wondered why nothing was available to accommodate his friend, and. . . .

In many ways, Mendelovich typifies the average inventor: the key question is not if, but when. There is no doubt in his mind that the concept is ideal; it’s just a matter of time before his “Toothpaste Holder and Dispenser,” which allows for one-hand manipulation, is on every bathroom wall.

In other ways, though, Mendelovich bears no resemblance to the typical inventor. His briefcase is overlowing with material — information from anyone and everyone concerning marketing and production, firms that can help, outfits to avoid. Mendelovich knows all the universities that offer counseling, all the books worth reading, all the minutiae about intricacies of the patent process. Some inventors, wanting to fulfill their curiosity, spend an afternoon in Crystal City. Mendelovich spends days there.

Most inventors pay little, if any, attention to marketing, while Mendelovich is building his entire plan around it. His original idea, he believes, is not perfect, so he has been in contact with professional designers and engineers, who will construct a new model. It took three years to receive the first patent, and now he is starting over. But the time factor apparently doesn’t bother him; it is only the end result that matters. After all, he’s not talking about one or two small claims — this is the mother lode. “I can see a future in this,” he says.

Sidebar: Not-So-Great Moments in the History of Philadelphia Inventions

Sidebar: Got Any Ideas?

This article, by Alan Green and Bill Hogan, originally appeared in the March 1982 issue of Philadelphia magazine.