1942: A Summer Sampler

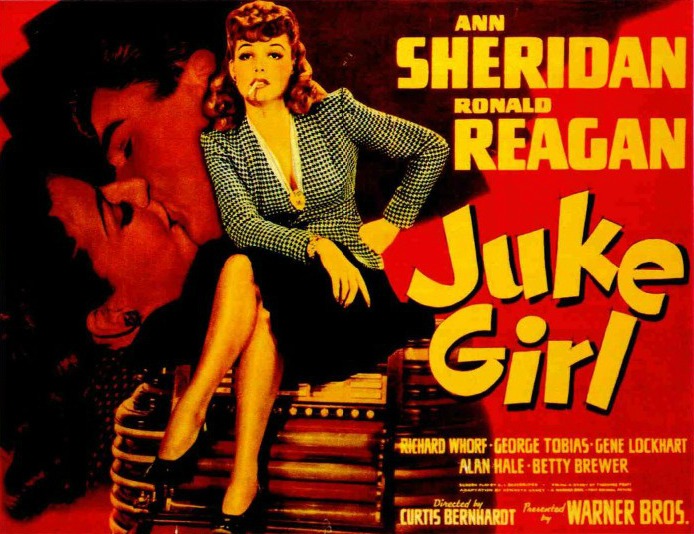

Dutch’s Treat. Forty years ago, Memorial Day moviegoers at the Ambassador Theater, 18th Street and Columbia Road, N.W., saw Ann Sheridan and Ronald Reagan in “King’s Row.” In probably his best motion-picture performance, Reagan’s leg is amputated, and he utters a classic line — “Where’s the rest of me?” — which later would become the title of his autobiography. At the same time, one of Reagan’s eminently forgettable films, “Juke Girl,” was playing across town at the Village Theater, 1307 Rhode Island Avenue, N.E.

The Monumental Meltdown of 1942. Donald M. Nelson, director of the War Production Board, told Congress on June 25, “We may indeed find it necessary before we are through to go well beyond what is normally considered scrap.” What did he have in mind? “Any one of us can walk down any street in Washington and see substantial quantities of metals that might thus be used” — including statues of Generals Grant, Jackson, Scott, and Thomas, plus those of a handful of other war heroes. Luckily for Washington’s pigeon population, the meltdown plan was later scrapped.

Take Me Out to the Salvage Rally. Washington’s first twilight baseball game on July 17 attracted 11,000 or so fans, who watched the Senators shut out the Detroit Tigers 3-0. But a month later, on August 24, 16,000 people jammed into Griffith Stadium for a mammoth salvage rally, the first of its kind in the nation. Officials estimated that 30 tons of scrap metal, rubber, and rags were collected, including a bird cage offered by Miss Eleanor Abernethy of 1333 Belmont Street, N.W.

Show-Stoppers of 1942. The night before a gigantic, star-studded Bond Rally on the south steps of the Treasury Building, the National Theater staged a “command performance” for Washington servicemen and VIPs, starring the likes of Bing Crosby, James Cagney, Connie Boswell, and Dinah Shore. But an impromptu snatch of dialogue between orchestra leader Kay Kyser and actress Hedy Lamarr brought down the house. Kyser: “Hedy, I don’t know how to say this . . . – but tonight . . . after the show . . . when we’re all alone, and the moon is out, let’s you and I, let’s, let’s, let’s . . .” Lamarr (in an inviting tone): “Yes . . .” Kyser: “Let’s go out and swipe some hubcaps.”

The 1942 Award for Editorial Overkill. Washington’s Riverside Stadium hosted something called a walkathon that summer — a round-the-clock endurance contest won by the last couple left on their feet. The Washington Post, as readers might have gathered on July 31, didn’t exactly like the idea, calling it “one of the most revolting spectacles ever produced anywhere,” “the lowest form of entertainment ever devised,” and “the most sadistic spectacle of disgusting exhibitionism in America.” And in case anyone missed the point: “Washington — or a sadistic segment of it — had never seen its equal in unmitigated insanity.”

Reichsmarks from Heaven. James M. Landis, executive director of the Office of Civilian Defense, warned Washington souvenir hounds in August to keep their hands off any fragments of Nazi shells, airplane fuselage, or other morbid debris that might drop in the city’s streets during an enemy air attack. “Failure to disclose their location to the proper authorities and to guard them against molestation,” Landis said, “may deprive the armed forces of needed information.”

That’s Right, Folks, and Don’t Forget Your Field Glasses. While resort towns up and down the Atlantic Coast worried that marauding German U-boats would bring ruin to the summer beach business, Baltimore Mayor Clifford B. Cropper looked on the sunny side of things. All those submarines, he said, would be one of Maryland’s biggest tourist attractions.

Roomers of the Worst Kind. Sometime in the summer of 1942, Sergeant Roy Blick of the D.C. vice squad became interested in The Hopkins Institute, a medical center occupying two five-room suites in an elegant apartment building near the Wardman Park Hotel, at Connecticut Avenue and Woodley Road, N.W. The Institute’s skilled therapists (including one named Wonder) attended to some of Washington’s most prominent and distinguished gentlemen, carefully recording their names and preferred treatments in three leather-covered ledger books. When Blick and the FBI raided it early the next year, residents of the quiet, tree-lined neighborhood were shocked to learn that patrons of The Hopkins Institute had routinely been rubbed the wrong way. The establishment was, said the FBI, “the most notorious call house in the East.”

Main Story: Washington in Wartime

This article originally appeared (as “Forty Years Ago: A Summer Sampler”) in the June/July 1942 issue of Regardie’s.