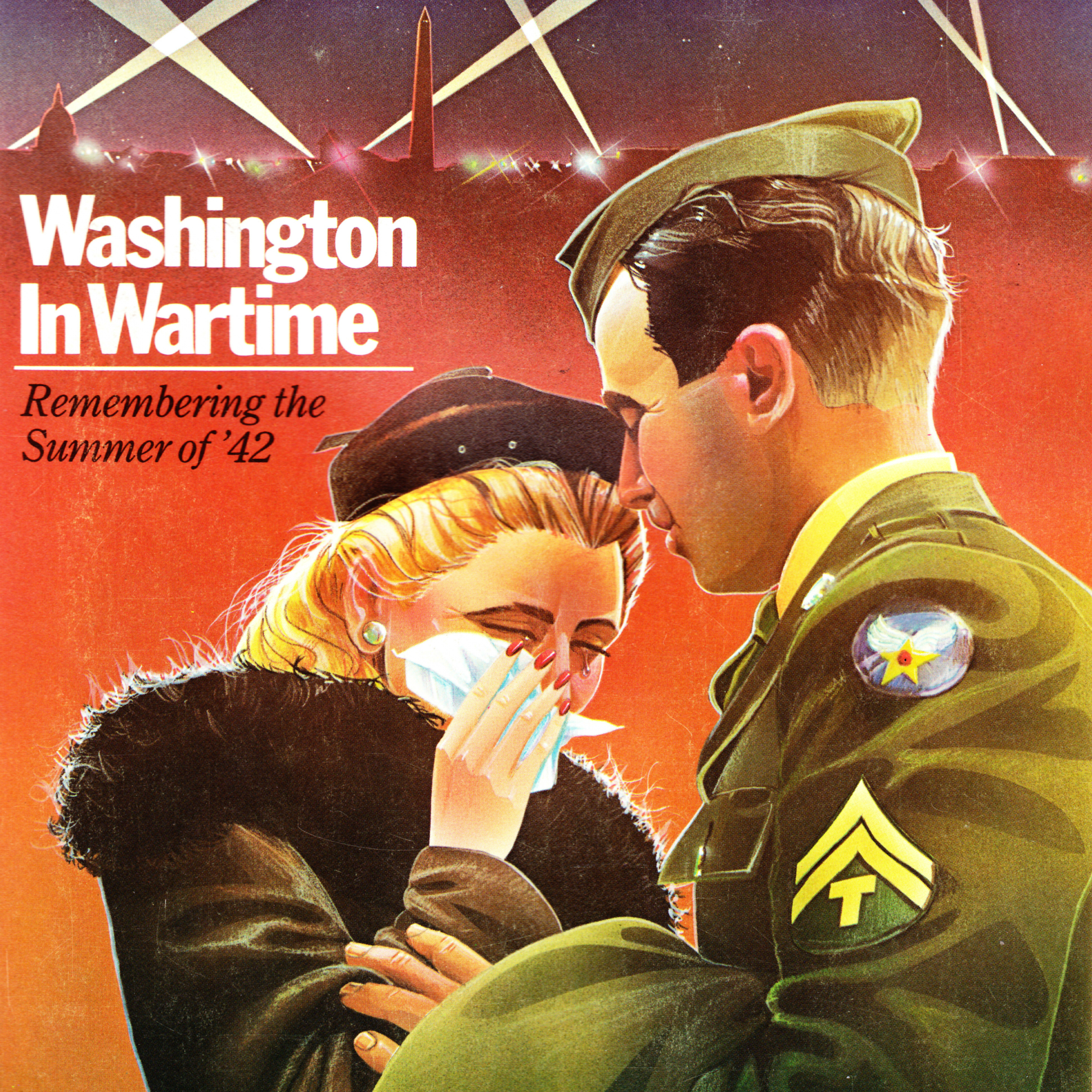

Washington in Wartime

A DENSE CURTAIN OF FOG gripped the Long Island coastline in the early hours of June 13, 1942, parted here and there only by misty beams of moonlight. Amagansett Beach, a sheltered stretch of rolling dunes and tall grasses, was deserted, serene.

But from five hundred or so yards out, a German submarine was disgorging an inflatable rubber lifeboat that would silently bring to shore George John Dasch, Ernest Peter Burger, Heinrich Heinck, and Robert Quinn, all top graduates of the Nazi sabotage school at Quenz Lake, just outside of Berlin. They carried more than $90,000 in U.S. currency, flawlessly forged Social Security and Selective Service cards, and enough explosives to cripple American airplane production and other war-vital industries.

The surreptitious landing on Long Island was the opening episode of “Operation Pastorius,” a frighteningly ambitious sabotage plan devised by Abwehr 2, the Nazi intelligence agency. Four days later, another German submarine would deposit a second team of four saboteurs in Ponte Vedra, Florida, just south of Jacksonville Beach. The two teams were to rendezvous later on at Chicago’s Commodore Hotel.

It was less than six months after Pearl Harbor. The German high command, though confident of its military might in Europe, deeply feared the sleeping American industrial giant, just now bringing assembly-line efficiency to war production. The German war machine had been buried by an American onslaught once before; Hitler was determined not to let it happen again.

Now, with the first saboteurs safely landed, members of the submarine crew reeled in a tow rope attached to the collapsible lifeboat. Heinck and Quinn sat on the beach, calmly puffing on German cigarettes and sipping from a bottle of brandy. Dasch, the team leader, heard an unfamiliar voice call out, and turned to find himself on the receiving end of a flashlight beam.

Dasch walked directly toward its source, confronting twenty-one-year-old John Cullen, a second-class Coast Guardsman assigned that night to patrol the beachfront. Cullen, of course, wanted to know who these men were and what they were doing; Dasch gamely replied that they were Southampton fisherman run aground. At that untimely moment, however, Burger emerged through the fog, dragging a bag and saying something in German. “Shut up, you damn fool,” Dasch barked. But it was already too late.

After realizing that Cullen was unarmed, Dasch threatened him, suggested “he forget the whole thing,” and pushed a wad of bills on him as a bribe. With some hesitation, Cullen accepted the money, thinking the most important matter at hand was to get back to his Coast Guard station in one piece. “Now look me in the eyes,” Dasch said. As he stood eyeball-to-eyeball with this stranger — who kept repeating, “Would you recognize me if you saw me again?” — Cullen had the distinct impression he was being hypnotized.

As the Coast Guardsman backed away and disappeared through the mist, Dasch assured his men that everything was all right, and the group proceeded to bury everything they had brought ashore, down to the last cigarette butt. By the time Cullen and three other Coast Guard officers armed with .30-caliber rifles returned to Amagansett Beach, only fog remained.

LATER THAT DAY, some 250 miles to the south, residents of Washington, D.C., were receiving detailed instructions for the city’s first full-scale, dusk-to-dawn blackout. The eexercise had been planned so that authorities of the First Interceptor Command could observe “the ability of this coastal area to conduct the protective measures considered essential in the event of an enemy attack.”

The darkened buildings and deserted streets of a citywide blackout promised Washington some sort of overdue calmness, even serenity. Forgotten, at least for the moment, would be the headaches and heartaches of the Summer of 1942: the unending and overpowering influx of strangers, which led to overcrowding, rudeness, and despair; the shortages and rationing, which led to waiting lines, hoarding, and black markets; and the long hours, which led at first to short tempers and then only to exhaustion.

Forty years ago, Washington was transformed into a sprawling, brawling boomtown wholly unlike the comfortable city its residents had known before. The nation’s capital, for better or worse, had been thrust suddenly into the role of nerve center for the entire Allied war effort, and it was feeling — at times reeling from — the strain.

In the darkest moments of that summer, Washingtonians were given to wondering whether the air-raid drills and blackouts might only be dress rehearsals for disaster. Somewhere, as unsettling as it seemed to any who thought about it, the capital of the United States was just a pushpin on an Axis map.

On the other side of the world, Japanese forces now controlled the entire South Pacific, and their invasion of Australia was reported to be imminent. Close to home, the relentless German U-boats, prowling East Coast shipping lanes in wolf packs, had sent more than two hundred Allied vessels to the bottom of the sea, bringing trans-Atlantic supply efforts to a virtual standstill. At times, American military preparedness — and, for that matter, any comprehensive planning for civilian defense—seemed pitifully short of what was needed.

The nation’s newspapers carried accounts of new draftees being trained with broomsticks and eggs instead of guns and grenades. In Washington, the soldiers guarding government buildings and sentries looking out over the Potomac River had World War I hand-me-downs: doughboy helmets and Springfield rifles. Some of the anti-aircraft batteries silhouetted at night atop Washington’s meager skyline were manned by wooden mannequins, which hardly was a reassuring discovery for Washington’s jittery populace.

If any Washingtonians had been tempted to consider the city’s first blackout as only a nocturnal novelty, the events of the following weekend would be sobering. Even with gasoline rationing, thousands managed to make it to the beaches of Maryland and Virginia in search of relief from the searing summer sun. Those who went down to Virginia Beach got more than they bargained for. Shortly after midday, they heard deep rumblings merge into an awful, almost deafening roar. Then came the numbing shockwaves from back-to-back explosions, and they watched in horror as flames engulfed two merchant ships hundreds of yards out. One, totally crippled, sank out of sight.

As the Summer of 1942 settled in, all eyes turned to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and the growing government over which he presided. Even his resonant and reassuring voice could not completely calm the nation’s rattled nerves, nor those of its capital.

It was wartime in Washington. Fueled by fear, rumors swept across the city with startling speed — rumors, even, that Nazi submarines were landing saboteurs and spies on American beaches.

THERE HAD BEEN A TIME, after the shock and anguish of Pearl Harbor had faded like a bad dream, when the newness and excitement of the war ushered euphoria into Washington. The mere rush of new residents — with their peculiar accents and appearances, manners and morals—injected a refreshing dose of exuberance into a stodgy, somewhat Southern, city.

Out of Washington’s jukeboxes wafted tunes like “Goodbye, Mama, I’m Off to Yokohama” and “You’re a Sap, Mister Jap,” and crowds at public gatherings spontaneously broke into choruses of “The Star-Spangled Banner” and “God Bless America.” Sugar rationing had begun in May, but it was an altogether tolerable annoyance in the beginning, a roll-up-the-sleeves sacrifice; besides, most people who could afford it hoarded huge bags of the stuff.

There were jokes about the housing crunch and Washington’s willing women and the burgeoning bureaucracy. The War Production Board was one of the prime recipients of the snickering: it had, for example, something called the Biscuit, Cracker, and Pretzel Subcommittee of the Baking Industry of the Division of Industry Operations (the BCPSBIDIOWPB), which stumbled on the remarkable discovery that one byproduct of the cracker-making process — crumbs — would actually thicken up canned soups.

Old-line Washingtonians, of course, grumbled that the city was going to hell in a hand-basket, and there was some truth in the observation. They were forced to suffer the indignities of waiting in line alongside total strangers, and were treated as brusquely as everyone else in the city’s eateries — no matter how expensive or exclusive — where the unwritten rule was Eat Quickly, Pay Up, and Get Out. The feeblest protest invariably would earn the standard rejoinder — “Don’t you know there’s a war on?” — an insultingly trite indecency to which there could be no intelligent response.

Wartime, in other words, did not gently tiptoe up to Washington. The city was rudely jolted from its normal state of somnolence by a cacophony of construction and congestion. In earlier summers, the nation’s capital would have been just emptying out; now, as the federal government was being converted at breakneck speed into an assembly-line bureaucracy, it was furiously filling up. Soon there would be too many people working too hard and living too close together.

For probably the first time in Washington’s history, government simply could not keep up with itself. The Pentagon — by any measure a mammoth, if not monstrous, edifice — had been built from the bottom up in just eight and a half months. Inside, more than 35,000 workers walked through 17½ miles of corridors and drank 25,000 cups of coffee a day. It was ballyhooed as the world’s biggest office building, but it was not big enough. Uncle Sam commandeered office buildings and downtown apartment houses at a rapid clip — one count had it at 189 — booting out residents who had nowhere else to go.

The picture-postcard parts of Washington, around the Mall and the monuments, soon seemed like some kind of Downtown Dogpatch, as massive work crews threw up huge, prefabricated office buildings. They quickly were christened “temps” or “tempos,” shorthand for temporary. It was an eye-opening contrast in architectural aesthetics: Next to majestic palaces of gleaming white marble were barracks-like boxes of mouse-colored asbestos siding.

All this and plenty more was needed for the nation’s nerve center, but Washington also was being transformed into a world capital. The British, for example, maintained almost a shadow government in the city, with some five thousand diplomats, soldiers, and civilians. When the British Embassy’s contingent outgrew two new annexes on Massachusetts Avenue, it was split up and moved into a big apartment building and the entire top floor of the Willard Hotel. Other consulates followed suit on a smaller scale.

In this respect, the British were lucky: No one else in Washington seemed to be able to find a hotel room. The thousands of people needing a place to sleep and shower while looking for permanent lodging clogged everything up. At the time of the 1940 Census, Washington had ranked 11th in population among American cities; by 1942, the massive invasion of government job-seekers, influence-peddlers, and assorted hangers-on had bumped the city into eighth place.

The dingiest boarding houses had no trouble finding tenants, even with exacting admission standards and exorbitant rates. Newly arrived government workers queued up in long lines to look at vacant rooms and apartments; many soon discovered, however, that palm-greasing was more effective than persistence. Some families were forced to ship their children off to relatives in other cities because they could find no affordable housing in Washington — even back then, large homes in certain neighborhoods were fetching $1,000 or more a month.

Washington hotels tried to cope with the crisis, but found it nearly impossible. After hours, they set up cots in their anterooms, parlors, and even restaurants. Some hotels, alarmed at the number of guests who were staying for unusually long stretches, placed three- or five-day limits on occupancy. But even these restrictions accomplished little: Patrons simply shuffled around town in a kind of musical-chairs routine, accompanied by their luggage-laden bellboys.

The city’s transportation system nearly cracked under the pressure. The streetcars were jammed beyond capacity, even after all the seats were ripped out to allow passengers to stand shoulder-to-shoulder, swaying and sweating. Washington’s fleet of taxicabs was shrinking, and a force of under seven thousand struggled to serve a metropolitan-area population of more than one million. Fare-sharing became commonplace, as did another previously rare form of urban transportation: hitchhiking.

But the city’s cabbies, as could have been expected, seemed best able to keep everything in perspective. Washington, one of them said, was “the greatest goddamn insane asylum of the universe.”

NO PLACE IN WASHINGTON BETTER EXEMPLIFIED the new pressure-cooker pastiche than cavernous Union Station, once a pleasant enough place, but now a sea of cattle-like humanity. People pushed and pulled, yanked and yelled, in one big blur of motion and sound. Many seemed in too much of a hurry to get somewhere; others simply gazed through the gates at those lucky enough to have a ticket out of Washington.

Military uniforms—many of them from distant parts of the globe—imparted to the station a kaleidoscopic tint, as soldiers and sailors passed through the major North-South railroad hub on the East Coast. Scalpers methodically worked the long lines at ticket windows, selling black-market Pullman reservations at steep markups and staying on the lookout for the eagle-eyed and fleet-footed government gumshoes from the Office of Price Administration.

Businessmen heading into town in search of a lucrative defense contract (or a piece of one) were well-represented in the typical train-station crowd, too. They soon would find themselves dealing with a new breed of Washington wheeler-and-dealer: the “five-percenters,” so named for their standard cut in a government deal. (Some, however, still preferred to call them lobbyists.) Most of the small-town businessmen went home with nothing to show for their entrepreneurial excursions but unbridled contempt for the capital. “Washington’s a funny town,” one said. “It’s got scores of hotels, and you can’t get a room. It’s got five thousand restaurants, and you can’t get a meal. It’s got fifty thousand politicians, and nobody will do anything for you. I’m going home.”

Then there were those flowing into Washington in search of a home, or at least a job. They would keep the gears of government running smoothly and process the most precious commodity in the nation’s capital — paper. Civil Service recruiters had fanned out through the nation in search of typists, stenographers, file clerks, switchboard operators, transcribers, mail sorters, and so on. By war’s end, some 280,000 would come to town, three-quarters of them women (average age, 20).

Lured to the seat of government by high wages — and, fumed one congressman, promises of “plenty of dates” from their hometown newspapers — most found it difficult to make ends meet in Washington. They were the “14-40 girls” (a nickname derived from their annual government salary of $1,440) and there were so many of them that the federal government had to build entire miniature towns of dormitories and apartments. Among other things, they pushed D.C.’s marriage rate skyward and inspired a genuine bonanza for local jewelers, who happily reported up to 300 percent increases in wedding-ring sales.

Union Station also had its share of “undesirables.” Bookies, numbers-runners, prostitutes, and other forms of urban lowlife hung around the shadowy areas of the domed concourse, or milled around outside as if they had something to do. But at least they were professionals in their respective trades. The amateurs were the “khaki-whackies,” or “V-girls,” teenagers spellbound by the mystique of uniforms. They flitted and flirted about in search of conversations with military men—all in the hope that it might lead to a movie, a drink, a trip to the Glen Echo Amusement Park, or some other, more powerful, cure for loneliness.

The V-girls sported a standard uniform of their own: Sloppy Joe sweaters, bobby sox and saddle shoes, and neon-red lipstick. Such was their reputation that other teenagers, with more wholesome notions of recreation, avoided any semblance of the get-up for fear they might be pegged by young servicemen as easy marks.

Washington, like most major cities during the war, struggled to understand its younger generation’s declaration of independence. One of the city’s “14-40 girls,” in writing a newspaper essay on the miserable life in boarding houses, included this revealing paragraph:

“In fact, by the time we’ve reached the stage when our parents permit us to wander this far away from the family fireside we should be able to order our lives as we wish. By this time most of us have decided whether we are going to be good little girls or naughty little girls — and we shall continue to be good little girls or naughty little girls whether or not there is an eye at the keyhole.”

For those young people gripped by passion, and perhaps fortified by drink, there often was the vexing question of where to “do it.” Hotels, of course, were almost always out of the question, because of the citywide room shortage. Boarding houses presented the irritating and ever-present eye-at-the-keyhole problem. Automobiles, which afforded a modicum of privacy, were not supposed to be used for pleasure driving (gasoline was rationed and hard to find) — or, presumably, pleasure parking.

As a result of all this, Washington-area parks enjoyed a new surge of popularity, especially in the evening hours. Wooded tracts like Rock Creek Park were a favorite, though strangers out for a nighttime stroll posed obvious risks to couples not wanting to be disturbed or discovered. Even the grounds near Arlington Cemetery were a popular locale for liaisons. Did shame, asked some Washingtonians, know no bounds?

Parents, with some justification, sought to insulate their older children from this parade of promiscuity, lest they be drawn into it. A major issue of public debate, in fact, was the matter of whether brothels near military bases ought to be legalized and supervised. “What substitute do we offer for prostitution?” asked naval surgeon Winfield Pugh Scott. “Like it or not, somebody’s daughter.”

And from Captain Rhoda Milliken, chief of the Women’s Bureau of the Metropolitan Police Department, came a warning in early June to parents all over the nation. “If your daughter is emotionally unstable, keep her away from Washington,” she said. “Parents who have not bothered to instill character and responsibility in their daughters are courting trouble by letting them come here.”

AMONG THE THOUSANDS OF PEOPLE elbowing their way through the crush in Union Station at around 7 p.m. on June 18, 1942, was George John Dasch. The day before, in New York, his hotel had managed to get him a room at The Mayflower in Washington, where he now was headed to try to reach J. Edgar Hoover at the FBI. Sometime during the last few days, for reasons not entirely clear, he had decided that the Nazi sabotage plan should be put to a premature end.

Hoover, as it turned out, was in New York, but Dasch was able to get through to FBI agent Duane L. Traynor the next morning, who hastily arranged for him to be brought to FBI headquarters. Over the next few days, Dasch spelled out everything in intricate detail — names, dates, places, times, targets — the logistics that had been drilled into his consciousness at Quenz Lake.

The prime targets of the two-year Nazi sabotage plan included hydroelectric facilities at Niagara Falls; three of the nation’s major aluminum plants; bridges, reservoirs, and canals; and the legendary horseshoe bend of the Pennsylvania Railroad at Altoona, the destruction of which would have stymied the state’s anthracite coal industry. And to undermine American morale, already sagging, the saboteurs were instructed to place time bombs in lockers at major railroad terminals and in department stores and other crowded places.

Abwehr’s industrial sabotage experts had equipped their eight trainees with compact arsenals of destruction, including, among other items, bombs built to resemble chunks of coal and abrasives designed to ruin railroad engines. There also were fountain pens with powerful incendiary compounds hidden inside.

There was so much that Dasch simply could not remember it all, but Abwehr had even provided for that eventuality. The details were written in invisible ink on several pocket handkerchiefs, which Dasch handed over to the federal agents. The FBI began rounding up the unusual suspects.

By the time FBI Director Hoover made the incredible disclosure to the nation’s press on June 28, five of the Nazi saboteurs already had been arrested, and the remaining two were under surveillance. Dasch, at 39, was the oldest; 22-year-old Herman Haupt, an American citizen, the youngest. Amid frenzied cries for summary execution, all were brought to the District of Columbia Jail near the southeast corner of Washington, where a second-floor wing of cells had been cleared for them. Justice, or some version of it, would be swift. A 20-by-100-foot makeshift courtroom was under construction in the Justice Department building, so that a rare military trial (rare because it was not a court martial) could begin only four days later.

The entire trial was to be shrouded in secrecy and security, only fueling rumors and speculation along the way as to what went on inside the closed doors of the courtroom. It was widely assumed from the beginning that the death penalty, for most if not all saboteurs, was a foregone conclusion. Reporters assigned to cover the trial found a few inside sources, but most of their stories focused on descriptions of witnesses heading in and out of the special chamber. On one occasion, reporters were allowed into the courtroom for fifteen minutes; later that day, Washingtonians could read graphic portraits of how the saboteurs had fidgeted in their seats.

As the trial of the eight Nazis pushed grimly through July 1942, its grasp on the attention of Washington was momentarily loosened by an episode of equal drama. Two years earlier, a mysterious sniper had terrorized the city’s black community with a string of nighttime shootings. Four blacks were killed, including 17-year-old Hyland McClaine, gunned down as he walked along Rock Creek Parkway near Virginia Avenue, N.W. John Eugene Eklund, a former college student now in his mid-20s, had been sentenced to death for McClaine’s slaying. But Eklund had been granted several stays of execution. And after one of the prosecution witnesses admitted he had perjured himself, Eklund won a new trial.

The jury in his second trial had deadlocked, so Eklund was being returned to jail — the same jail holding the Nazi saboteurs. As two deputy marshals opened the doors to the van in which he had been transported to and from District Court, Eklund, still handcuffed, lunged past them. It was 10:20 p.m., the city was in the middle of a blinding July rainstorm, and the marshals lost sight of Eklund within moments after he bolted away. No shots were fired, and Eklund did not care to look back.

The manhunt that followed was said to be the most intensive since John Wilkes Booth escaped after shooting President Lincoln. Every available Washington policeman, plus a special team of fifty soldiers, scoured the swampland bordering the Anacostia River. Four boatloads of harbor police patrolled the shore, and Coast Guard boats plowed the Anacostia and Potomac rivers in case Eklund tried to swim away. Two days later, even as the Potomac was being dragged for his body, Eklund was arrested. He was walking nonchalantly along Peabody Street, N.W., between 7th and 8th Streets, somehow free of the handcuffs he was wearing at the time of his escape.

Eklund later said he had panicked as he was brought back to District Jail. “It was a dark night and I thought they were trying to put me in the electric chair,” he said. “I hadn’t planned to try to escape, but when I saw the rain and how dark it was, I lunged past the deputies and ran.” The day after his capture, the jury’s verdict was unsealed: guilty of second-degree murder, with a maximum possible sentence of fifteen years to life imprisonment.

Eklund probably was fortunate. If it had been the other way around — a black man convicted of gunning down a white youth — even a lifetime sentence would have been decried as too lenient.

WASHINGTON DID NOT WORRY MUCH about justice in the Summer of ’42, or at least about equal justice. The city’s Southern roots still ran deep, and blacks, though they constituted more than one-quarter of the city’s population (the highest ratio in the nation), were rarely treated as more than second-class citizens — even by those who were much more recent emigrants.

Many of Washington’s blacks lived in the notorious “alley houses.” Life in the alleys was so vile, so squalid, that there had been riots in earlier parts of Washington’s history. But little had been done to improve conditions — several families still crowded into single rooms, sanitation was virtually nonexistent, and most were helpless against the epidemics that swept swiftly through the streets. Largely because of Washington’s awful alleys, the city’s death rate from tuberculosis was the highest in the nation.

The boomtown bureaucracy should have been expected to help lift many of Washington’s blacks out of poverty, but it did not exactly work out that way. In 1941, A. Philip Randolph, president of the Brotherhood of Pullman Porters, threatened a massive march on the nation’s capital to protest discrimination against blacks in defense industries — one survey showed that more than half of the nation’s defense contractors closed their doors completely to them. The Fair Employment Practices Commission, created by President Roosevelt to help change the situation, was given legal authority only to investigate complaints, not to resolve them.

There were other injustices and incongruities. The help-wanted and housing ads in the city’s newspapers often included racial restrictions. Even if the city’s hotels had been empty, blacks would not have been able to book a room. The armed forces were segregated, and in the military parades through Washington streets, black regiments marched along toward the trailing end of the procession. And there would be demonstrations against the Capital Transit Company because it refused to hire blacks as conductors and motormen, fearing that the whites would quit. Moreover, when the streetcars passed over the District line into Virginia, a particularly invidious practice ensued in which blacks would have to move to the back.

And even in the backyard of the U.S. Congress, black and white “14-40 girls” would work side by side in government office buildings during the day, only to return to segregated housing at night.

BY JULY 20, THE GOVERNMENT HAD WRAPPED UP its case against the eight Nazi saboteurs, asking that they be executed by hanging or firing squad. During the eleven days.of secret hearings, few details of the case against them leaked out, but there were enough to provide grist for lunch-counter chitchat. As some Washingtonians went about their business, they caught fleeting glimpses of a caravan of armored cars, prison vans, and motorcycle outriders speeding through the streets, carrying the eight Germans back and forth from jail.

To expedite the resolution of the government’s case against the Nazi saboteurs, the Supreme Court convened in a rare special session on July 29 to decide whether the military commission trial was constitutional and whether President Roosevelt was empowered to deny the defendants a hearing in civil court. A line began forming outside the Supreme Court building at nine in the morning, and at noon, three hundred spectators were led into the chamber. But as soon as word came that the eight defendants would not appear, most of them left.

The Supreme Court cleared Roosevelt’s path, and he moved swiftly. Dasch and Burger, for cooperating with the prosecution, were spared from the death penalty by presidential commutation. (Dasch got thirty years at hard labor, Burger life imprisonment.) Roosevelt was determined to keep crowds away from the jail by keeping a tight lid on his plans, but a grisly death watch began nonetheless.

At one point, four soldiers — three American and one British — offered “to save the government some money on electricity” by serving as a firing squad. Reporters and photographers traded shifts outside the jail to watch for any signs that lights were being dimmed, which was said to be a telltale sign of an impending execution.

On August 9, FDR’s orders were carried out with precision. The six Germans were served a breakfast of scrambled eggs, bacon, and toast at 7 a.m. At half past the hour, they were informed one by one that the president had ordered their executions. Each reacted with complete equanimity. At one minute past noon — as an air-raid siren masked the sound of drizzling rain outside — Herman Haupt was strapped into the electric chair; by four minutes past one, a team of four professional executioners had completed its work.

Later that day, the six bodies would be taken out to a potter’s field at Blue Plains, where they would be buried in unmarked graves.

THE SUMMER OF 1942 HAD ARRIVED on Washington’s doorstep with a military parade, the first since U.S. entry into World War II. In earlier years, Memorial Day celebrations would bring whoops and yells, whistles and applause, cheering of all kinds. This time, however, it was strangely silent. Few of the more than 100,000 spectators along the parade route even talked to one another. The grim reality of wartime seemed to have sunk in, to have stunned them just a bit, At times, the rhythmic thudding of military boots against pavement was all that could be heard, with the occasional punctuation of a corporal’s “hep, hep.”

And as the summer drew to a close, it would be much the same. Unlike the Labor Days of earlier and happier times, there were no speeches, no rallies, no great picnic crowds. There was no holiday, really, because Washington had accepted the normalcy of wartime. No one knew how long the war would last, but it was at least clear that Washington and the rest of the nation were in for the long haul. There were some signs of hope, even of happiness. More than 16,000 people had crammed into Griffith Stadium for a huge salvage rally heavily laced with patriotism. They brought with them more than thirty tons of scrap rubber and metal—the admission “tickets” — and laughed with Jimmy Cagney and sang with Gene Autry.

While much would get worse — rationing would reach deeper into every Washington household — by the end of the summer, most who lived in the city had finally adjusted to the annoyances and figured it made sense to do the best they could under the circumstances.

For better or worse, the wartime Summer of 1942 had ended Washington’s era of innocence. Before the war, Washington had been a somewhat sleepy, Southern town that frowned on unescorted women walking down the street. It had considered itself invulnerable, its manners invariable, and its daughters inviolable.

Now, with the passing of the Summer of 1942, all that had changed. And Washington would never be the same again.

Sidebar: 1942: A Summer Sampler

This article originally appeared in the June/July 1982 issue of Regardie’s.