The Bad News Bearers

WITHIN CERTAIN QUARTERS, Terry Merrifield’s name is enough to provoke a barrage of expletives. Many people have roughly the same opinion of him that Jackie Onassis has of photographer Ron Galella. He has been threatened with everything from lawsuits to premature retirement; “I’m going to put a hole in your head,” a man he’d never met told him.

It’s all in a day’s work, because Merrifield is a professional process server. He will do virtually anything to guarantee that people have their day in court, whether they want it or not. He shows little fear and no favoritism; he will serve court papers on anybody — and he has, from Korean influence peddler Tongsun Park to District of Columbia Mayor Marion Barry — with the possible exception, he says, of his mother.

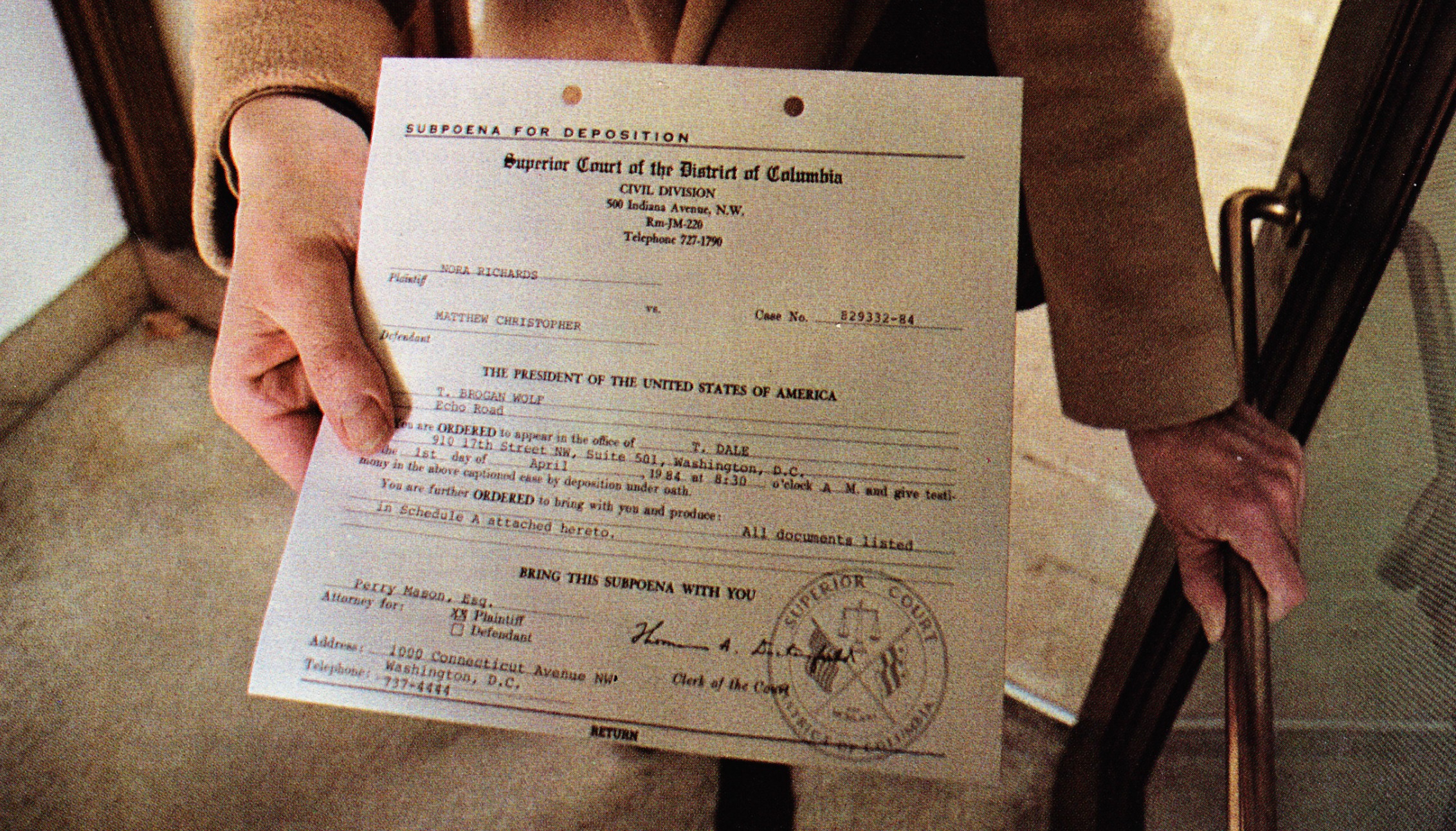

To see that court papers fall into the right hands, process servers need the right blend of guile, brains, and bravura. In many cases they must succeed where others — typically local sheriffs, but sometimes even their own competitors — have failed. Process serving amounts to the judicial system’s point of entry: Few legal proceedings can begin without the delivery, usually in person, of a summons ordering the defendant to appear in court. And frequently subpoenas must be served to compel witnesses to testify, either through depositions or in person.

Until two years ago attorneys could pay the federal government to have U.S. marshals serve their official court orders, summonses, and subpoenas. Because the fees were as low as $2 a serve, however, the operation was losing money in a big way — up to $5 million a year, according to one General Accounting Office estimate. Congress finally ordered the U.S. Marshals Service to concentrate on criminal cases, which left process-serving in civil suits to local authorities and private-sector practitioners.

The switch, appropriately enough, came on April Fools’ Day, 1982, and eagle-eyed entrepreneurs have been staking out their territory ever since. The bad-news business has become a bull market. Today dozens of companies in the Washington area will serve court papers for a fee, up from just a handful in 1982.

Merrifield, who left an 11-year-old career as a deputy U.S. marshal to cash in on the anticipated boom, has not been disappointed. Last year his firm, Marshall’s Metro Service, which is based in Alexandria, grossed more than $170,000 in process-serving fees alone without the benefit of advertisements or even a listing in the Yellow Pages. Its client list, which is fast approaching 500, includes some of Washington’s legal powerhouses: Piper & Marbury, Shea & Gardner, and Williams & Connolly, for example.

A quick call to Marla Sanders, the president of Quick Call Process Servers, is enough to confirm that the field has become a bonanza. “Absolutely,” she says. “We’ve had a 500 percent increase in business.” To be financially successful, a process server must deliver quality as well as quantity, and Sanders is suitably concise in explaining why attorneys ask her firm to serve the hard-to-serve witness or defendant. “We’re good,” she says. “One way or another, we’re going to get them.”

Some of Sanders’s targets have had good reason to wish that wasn’t true.

Once, for instance, a law firm hired her company to locate a particularly elusive husband-and-wife team of real estate developers. Nailing one of them was easy enough: By posing as a representative of prospective blue-chip investors and supplying a sheaf of financial references, Sanders was able to set up an appointment with the wife. Once admitted to the woman’s office, Sanders smoothly served her with her court papers.

Snagging the husband, however, called for an even more outlandish sting. After learning that process servers were hot on his trail, he virtually imprisoned himself in his home and his office.

Shortly before the end of October, Sanders settled on an appropriate scheme. After dusk on Halloween she dispatched her youngest process server — outfitted in a red devil’s costume — to her quarry’s office, an elegant townhouse just off Connecticut Avenue in downtown Washington. After hearing a muffled cry of “trick or treat” and opening the door, the man suddenly found himself holding the court papers he had eluded for three months.

“You’re served,” said the devil.

PROCESS SERVERS SELDOM find getting their foot in a chronic evader’s door an easy assignment. If the victim lives in a high-security, high-rise apartment building, they may have to use stealth or subterfuge to gain entrance. Sometimes a simple ruse is all it takes: a delivery uniform and a package tucked under the arm, telephone repair equipment hanging from the belt, or a bouquet of flowers within view of the peephole.

But particular tough cases call for more exotic gambits. Consider, for example, the free-firewood ploy practiced by Robert Shaw, a private investigator and process server at the Falls Church detective agency Miller & Associates.

“We dressed up like firewood salesmen — we had a truck and everything —and knocked on this guy’s door,” Shaw recollects. “We told him we wanted to head back with an empty truck” and proceeded to asked him if he wanted some firewood for free — an offer he was apparently unable to refuse.

“As soon as he opened the door,” Shaw says, “we served him.”

A process server at the Washington firm Trackdown employs a blunter approach that he claims is surprisingly effective. “I’ll ring the doorbell until they get pissed off,” he says. “If they get pissed off, they’ll open the door.”

Process servers sometimes find it necessary to coax their quarry out of hiding. Tom Nail, process manager of Uffinger Investigative Agencies of Vienna, Virginia, recalls a difficult case that called for a particularly ingenious setup. After several unsuccessful attempts to serve a summons on a business executive with bad debts all over town, Nail decided to zero in on the man’s automobile, which he routinely parked on the street in front of his house.

One day, after determining that his victim was home, Nail angled his own car right behind the executive’s, got out, and examined its fender at close range.

Feigning distress, he began asking neighbors if they knew who owned the car. As a small crowd gathered, Nail saw the curtains in his quarry’s home crack open. Within moments, he says, the executive “came out running and screamed, ‘Oh, my God, you hit my car.’ ” Nail hadn’t, but he took advantage of the opportunity to hit the man with a summons.

Most professionals in the field do their best to avoid embarrassing the people they are hired to serve. They generally try to nail someone at home first; if they must go to his workplace, they prefer to present the court papers quietly and privately. For serving the unwilling, however, another setting may have to suffice.

Having learned that a chronic evader was to be a pallbearer at a funeral, Nail got his photograph and showed up for the services. His approach was gentle but to the point. “I got him off to the side,” Nail says, “and told him, ‘You can accept service now or make a big deal out of it.’ ” The man decided to accept.

MOST PROCESS SERVERS begin by peppering their clients with questions. Has the person been avoiding service? Where does he live and work? What is his daily routine? Who are his friends and business associates? What kind of car does he drive? What does he look like? (Photographs can be extremely important because often people sought by process servers claim they’re not themselves.)

“The more information the attorney can give you,” says an experienced server, “the better chance you’ve got.”

Armed with such knowledge, expert process servers can often score on the first try. (Most servers charge a flat fee of $20 to $40 plus mileage for three diligent attempts, so there’s a strong profit motive for early, effective service.) After a string of unsuccessful tries, a process server generally asks the attorney who hired him whether he should continue his pursuit. If so, they may agree on a ceiling that reflects the amount of time and trouble he estimates the chase will consume.

The sky is rarely the limit, but Merrifield says he has been offered up to $1,000 to serve court papers. Most process servers say their highest fees are

n the $300 to $400 range. Sometimes even the plaintiff is willing to pay to get his adversary into court. Shaw recounts that one plaintiff told him: “There’s a bonus in it if you can nail this guy.”

Experienced evaders give even the best process servers migraines. Some always commute to work by driving from a garage equipped with an automatic door-opener to the private parking garage of an office building. Others utilize a variety of string-along techniques to buy a little time for themselves that chew up valuable hours (or even days) of a server’s time. Still others make their intentions clear in their first telephone call from a server with a simple “No way,” “Get lost,” or “Go to hell.” For any self-respecting process server, those words represent the opening salvo in a war of nerves — and often wits.

Most expert process servers set up surveillance of a recalcitrant victim’s home or office — anywhere from an hour or two in the morning to 24 hours a day — to await the ideal opportunity to ambush their prey. But should no such opportunity arise, they are prepared to rely on a variety of guises and gambits to get the job done.

A few tales from the trenches:

♦ A man who has successfully thwarted process servers for months is dining at a downtown Washington restaurant. A server from Bisbey Associates has been tipped off that he’s there but doesn’t know what he looks like, so she kindly informs the maitre d’ that a gray Mercedes outside has its headlights on. After the waiters inquire of the patrons who have recently been seated, the unwitting victim emerges from the restaurant to the unwelcome words, “You’re served.”

♦ Uffinger Investigative Agencies’ process servers get a tip that an executive who has eluded them at every turn will be attending an evening performance at the Kennedy Center. As he and his wife make their way to their seats, a server greets — and serves — him.

♦ Frank Sinatra is trying to sue Washington author Kitty Kelley over her unauthorized biography of him, but she has been winning a cat-and-mouse game with his attorney’s process servers. As she enters an authors’ party at Herb’s restaurant near Dupont Circle, a man hands her an envelope and asks, “Will you autograph this for me, please?” No signature, of course, is required. A process server from Trackdown has struck again.

♦ As he leaves home one morning, an attorney who knows he is about to be sued breathes a sigh of relief; no process servers are waiting outside for him. After driving several blocks away he slows down for a stoplight, and a motorcycle pulls up alongside his car. Its driver, Merrifield, tucks a summons under the attorney’s windshield wipers and announces, “You’re served.”

Merrifield believes that what snags his subjects four times out of five is the element of surprise. Chronic evaders, however, may not be easy to surprise. Merrifield has sent his servers out in jogging suits to catch them unawares. He’s hidden in bushes and posed as an exterminator. He even served a doctor’s paramour with a subpoena to bring a divorce case to a speedy close. (“He came unglued,” Merrifield says. “After that, they’re ready to settle.”)

Having found that many of their targets are suckers for what seems like a good business deal, process servers are happy to provide a simulated one. Donald Uffinger once posed as a prospective buyer of a $2 million farm and was invited out to see the property. Uffinger’s host served him a snifter of brandy; Uffinger served his host a summons.

One of Uffinger’s favorite techniques — a diabolically effective one — is to arrange to have a victim paged at the airport and informed that a message awaits him at the ticket counter. A message indeed awaits, but so does a summons or a subpoena.

Once in a while a process server’s efforts to set up a simple business meeting unexpectedly save a good bit of expensive legwork. Rose Marie Morton, an owner of Bisbey Associates, once tracked a shady real estate operator for weeks. His home, a fenced-in compound with security guards, was impenetrable.

Morton called the man, mentioned that she did “a lot of condo work,” and deftly inquired whether he might be interested in having her refer potential investors to him. “I think we can make a lot of money together,” the man told her, whereupon Morton offered to stop by to discuss the arrangements. “No, no,” the man said, “I’ll come to your office.”

WASHINGTON’S PROCESS SERVERS seem to agree that three species of professionals account for most of their problems: doctors, lawyers, and police officers — though not necessarily in that order.

“Police don’t like to testify and hate to be subpoenaed by the defense,” one server says. “Everybody in the station will lie for them. It’s outrageous.”

Some doctors are wary of process servers because a summons could mean a malpractice suit and a subpoena could mean producing a patient’s medical records or appearing in court as a witness for a paltry fee of about $30. “Most doctors,” Merrifield says, “will not talk to you unless you have a check for $1,500.”

But process servers have learned how to cope with doctors who refuse to answer their doors at home or instruct their receptionists to summarily turn away all bearers of court papers. Some resort to the obvious gambit: posing as a new patient and booking an appointment. “We have to sit around and dream up ailments,” says Quick Call’s Sanders. “Sometimes we even have to get a referral.”

Such creativity, however, is not without its consequences. Sanders says that doctors have sued her firm — not for harassment, invasion of privacy, or similar infractions but for failure to pony up the “consultation fees” that her servers were billed for their bogus visits. However, she notes, “nobody has ever gotten a judgment against us.”

Because process servers are not required to be registered or licensed, no one knows how many of them work in the Washington area, but the pros’ best guess is around 200. Many servers are law students, paralegals, or part-time freelancers, so there is a lot of turnover. “It’s hard to get good people,” notes Sandra Bisbey. “Part of the problem is an image thing — they think it’s a really scummy thing to do, like being a bill collector.”

No special credentials are required to be a process server; one need only be a U.S. citizen 18 years of age or older and have no direct involvement in the matter under dispute. Some of the best worry that a few fly-by-night firms that take the money from lawyers and run have eroded the image of their profession, which, after all, is an important part of the legal system. Sanders says that a handful of process servers in the Washington area have begun to meet periodically with an eye toward forming a professional association.

Thousands of people, however, have no reason to doubt the skill or tenacity of the new breed of process server. They are undisputed champions of what often becomes a high-stakes game of hide-and-seek. “Eventually,” Uffinger says, “anybody can be served.” Most servers have success rates that border on the uncanny. If someone is foolish enough to try to evade them, they tend to take it personally and resolve to have the last laugh.

Service, you might say, with a smile.

This article originally appeared in the April 1984 issue of Regardie’s.

Bisbey Associates Frank Sinatra Herb's Kitty Kelley Marion Barry Marla Sanders Marshall's Metro Service Miller & Associates Piper & Marbury Process Servers Quick Call Process Servers Regardie's Robert Shaw Rose Marie Morton Shea & Gardner Terry Merrifield Tom Nail Tongsun Park Trackdown U.S. Marshals Service Uffinger Investigative Agencies Williams & Connolly