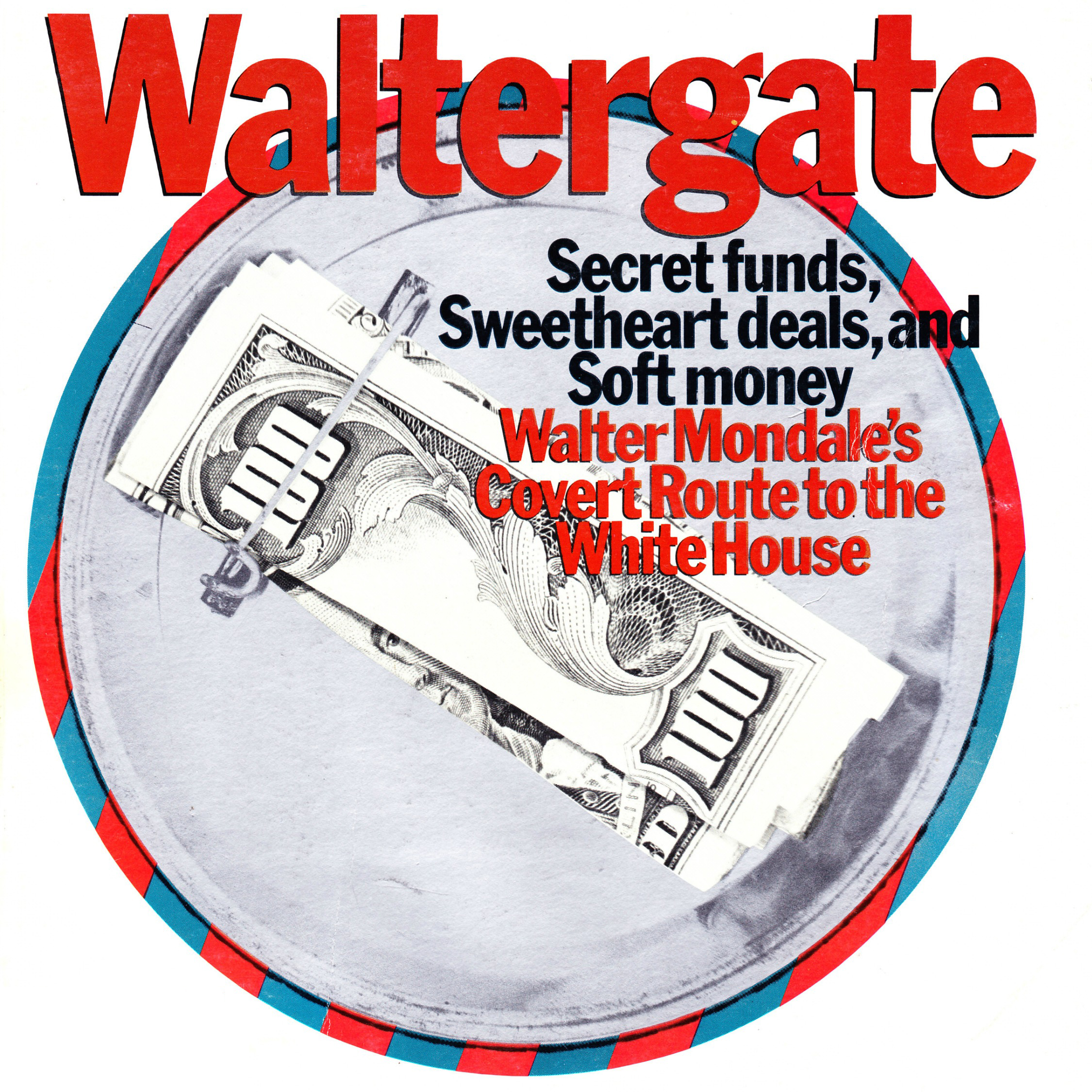

Waltergate: Secret Funds, Sweetheart Deals, and Soft Money — Walter Mondale’s Covert Route to the White House

In his 1975 book, The Accountability of Power, Walter Mondale described why he had abandoned his campaign for the 1976 Democratic presidential nomination in midstream. “I simply did not have the overwhelming desire necessary to do what had to be done to get elected,” he wrote.

By 1981 Mondale had put that hesitation aside. He was ready to do anything — and everything — that had to be done to win the nomination. 0ver the next three and a half years the former vice president would exploit the law firm that employed him, authorize the creation of secret checking accounts, and otherwise subvert the campaign finance reforms he had helped to enact in the wake of Watergate.

While other potential presidential nominees sought to obey federal election laws, Mondale and his advisers sought to bend or even break them. Even today, many operations of the Committee for the Future of America, the PAC they established to wage an undeclared presidential campaign, are shrouded in secrecy.

During its brief existence Mondale’s PAC covertly channeled funds from corporate and labor union treasuries to an undisclosed number of individuals and companies, including his law firm. It sought to hide the use of its contributors list by Mondale’s presidential campaign and later disposed of that asset — which had cost nearly $1 million to develop — in a secret sale.

And once Mondale had begun to campaign for the presidency, his debt-ridden PAC, which had officially shut down, managed to raise tens of thousands of dollars — with no employees, no telephones, and no office.

This is the story of how, for one presidential candidate, winning became the only thing.

Mondale’s Secret PACs

On October 6, 1982, former vice president Walter F. Mondale brought a cheering crowd of Wisconsin Democrats a message of hope: with their help, gubernatorial candidate Anthony S. Earl would win the November 2 election and return the state government to its progressive roots. Judging from the applause that the party faithful gave him, they liked what they heard.

Mondale was capping a one-day swing through Wisconsin with a speech at a $50-a-plate Democratic fundraising dinner. For more than a year and a half he had been traveling the nation as heir-apparent to the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination. At nearly every stop he contributed money to Democratic candidates, and this evening was no exception. With his arm around Earl’s shoulders, Mondale presented him with a $3,000 check from the Committee for the Future of America, the political action committee of which Mondale was chief spokesman and fundraiser.

Four months later an auditor for the Wisconsin State Elections Board, in reviewing Earl’s campaign finance reports, noticed the $3,000 contribution from Mondale’s PAC. There was, however, something curious about the money; it apparently had not come from the Committee for the Future of America — or at least not from the one registered with the Federal Election Commission in Washington, D.C. No committee with that name had ever registered with Wisconsin’s State Elections Board. A routine inquiry went out asking for CFA to clarify the matter.

What happened next was anything but routine. On March 1, 1983, the State Elections Board received a “Campaign Registration Statement” from something called the Committee for the Future of America State & Local IV, along with a campaign finance report disclosing $107,550 in income and a single expenditure, the $3,000 contribution to Earl’s campaign committee. Also in the envelope was the new committee’s notice of termination, informing the elections board that the PAC’s business in Wisconsin was finished.

One month later, in Mondale’s home state of Minnesota, officials of the Ethical Practices Board received a termination report from another Mondale PAC with a nearly identical name: the Committee for the Future of America State & Local II. In its first “Report of Receipts and Expenditures,” the PAC disclosed that in December 1981 it had received $36,000, including $10,000 from the National UAW (United Auto Workers) Political Action Committee and $25,000 from the Los Angeles County Council on Political Education. Its sole expenditure had been a $10,000 contribution to the gubernatorial campaign committee of Warren Spannaus, Minnesota’s attorney general, which it had made on December 30, 1981.

Under Minnesota law, the PAC had a problem: of the $36,000 it collected in December 1981, $35,000 had come from organizations that were not registered with the Ethical Practices Board, which led to a request that it comply with statutory disclosure requirements.

The PAC failed to respond, so nearly a month later the Ethical Practices Board sent it an “Official Notice of Delinquency.” The PAC’s general counsel, Washington lawyer Lynda S. Mounts, replied in a letter that the PAC “finds itself in the unfortunate position of being unable to obtain the required disclosure information” from its contributors. To avoid legal sanctions, the Committee for the Future of America State & Local II asked the Spannaus in ’82 Volunteer Committee for its $10,000 back, got it, and quietly went out of business — in Minnesota, at least.

The same PAC had surfaced in California on March 24, 1982, by filing a “Campaign Statement” with the secretary of state’s office. It reported collecting $1,000 and spending it on a contribution to the campaign committee of Los Angeles mayor Tom Bradley, who was running for governor.

Owing to loopholes in California’s campaign finance law, the Committee for the Future of America State & Local II was able to file disclosure statements that, while legal, were almost entirely false. In Minnesota, the PAC reported that it had $26,000 in the bank at the end of 1981, including funds from the Los Angeles County Council on Political Education; in California, it reported that that it had no money in the bank at the end of 1981. In Minnesota, the PAC reported that on January 19, 1982, it had received $10,000 from the general fund of the Region No. 13 United Food & Commercial Workers International Union (AFL-CIO) in Minneapolis; its California reports showed only a $585 contribution from that union.

‘These and other discrepancies in the way Mondale’s PAC reported its finances — perfectly legal, and perfectly misleading — would be impossible to discover except by sheer accident.

These two PACs represent only the tip of a soft-money iceberg whose mere existence has been the most tightly guarded secret within Mondale’s inner circle. Since 1981 the former vice president’s closest advisers have maintained a series of secret political funds that were specifically designed to circumvent the Federal Election Campaign Act and avoid any real regulation by state campaign finance authorities.

Mondale has made no secret of the Committee for the Future of America, the PAC he formed in early 1981 for the ostensible purpose of underwriting his political travels around the nation in support of Democratic candidates. He has, however, made a secret of its nonfederal clones: the Committee for the Future of America State & Local I, II, III, and IV, and unknown others that may exist.

These “subcommittees,” operating under widely divergent and largely ineffective state campaign finance laws, were designed to channel money into the Mondale operation that could not legally be accepted by the parent Committee for the Future of America: money from corporate treasuries, from the general funds of labor unions, and from individuals who had already given CFA $5,000 a year, the federal ceiling. These contributions were supposedly made to help Mondale’s PAC influence state and local — as opposed to federal — elections.

In reality, however, the only purpose behind Mondale’s state and local committees was to collect contributions that would have been illegal had they been deposited directly in the PAC’s account. No otherwise legal money — contributions conforming to federal election law — seems to have found its way into these committees.

Today it is virtually impossible to piece together how much money was routed through these soft-money accounts and where it went. The Mondale organization, ingeniously enough, planned it that way; by dividing the soft-money pie into an unknown number of slices (CFA State & Local I, II, III, IV, and so on), it precluded the possibility that one state’s aggressive campaign finance office might somehow force everything to be disclosed.

Mondale’s aides deliberately played another kind of shell game to guard against anyone finding out what was going on. By manipulating the movement of money from account to account, they could prevent disclosure, within one state, of how funds were actually raised and spent.

Details of a wide range of other payments were hidden by funneling them through something called the Allocated Operating Account, which merged the money with other CFA funds. Because Mondale’s PAC used this account to pay for many of its day-to-day expenses, its disclosure reports to the Federal Election Commission significantly understate its actual payments to an unknown number of individuals and companies.

As a consequence, Mondale’s Committee for the Future of America, which is widely assumed to have been a $2.5 million political operation, was larger than that. How much larger, nobody outside Mondale’s inner circle knows. Some of the PAC’s own employees, in fact, had no idea that their salaries were being subsidized by money from corporate treasuries, union dues, and individuals who had already contributed as much as they could under federal law. Michael Berman, Mondale’s legal adviser and the treasurer of his presidential campaign, declines to say how many covert PACs were operating, how much they raised, or where the money went.

In comparison to federal campaign finance law, state regulation is notoriously limp; at last count, 28 states allowed PACs to accept direct contributions from corporations and 41 allowed them to accent money from the general funds of labor unions. Because many states have no disclosure laws and others cannot enforce the laws they have, soft money can be siphoned up by a PAC like the Committee for the Future of America and spent in absolute secrecy.

In Ohio, for example, where CFA State & Local IV operated in 1982, the PAC reported raising $131,675 (including a $40,000 loan) and spending $4,209 on statewide campaigns. Its other spending, totaling $127,242, was listed as “expenditures by National Committee not attributable to Ohio.” The same PAC reported spending only $3,085 on behalf of Wisconsin candidates; it listed $128,373 as “expenditures by National Committee not pertaining to Wisconsin.” Details of these expenditures, whatever they are, presumably have not been disclosed anywhere.

And in New Hampshire, where CFA State & Local III operated briefly, its sole contributor during one reporting period was Philadelphia real estate developer Richard Rubin, who gave $4,600 on August 24, 1982. None of that money reached New Hampshire candidates. Five days earlier Rubin had given $5,000, his maximum legal contribution for the year, to Mondale’s parent PAC.

This way of doing business would surface in Mondale’s 1984 presidential campaign, when spurious delegate “committees” were invented to evade federal election law. By coldly calculating the most effective ways to exploit loopholes in state and federal campaign finance laws, Mondale’s advisers seem to have ignored one thing: By presenting Mondale as a politician who has diligently sought to obey the spirit of those laws, they have unwittingly made him vulnerable to charges of hypocrisy. So far, secrecy and subterfuge have been their only means of protecting him.

Even viewed in the most forgiving light, Mondale’s abuses of the nation’s campaign finance laws have been neither isolated nor inconsequential. Yet somehow he has remained unaccountable for wholesale violations of the reforms he helped enact a decade ago. During the entire 1984 Democratic presidential campaign, not once has Mondale been asked to explain his PAC’s secret solicitation of corporate and other contributions prohibited in federal campaigns. The public has not known the truth, and Mondale has not seen fit to volunteer it.

In January 1983 Mondale delivered a spirited speech before delegates to the California Democratic Conference, who also heard from six other presidential hopefuls. By nearly all accounts Mondale generated the most enthusiastic response. His words that day carried a certain conviction:

“I say it’s time, fellow Democrats, that we declare war on special-interest money in American politics. Let’s put a cap on campaign spending. Let’s plant controls on these PACs. Let’s end the loopholes of so-called independent committees. Let’s establish a system of public funding for congressional campaigns. And in these next two years let us say again that the government of the United States is not for sale. It belongs to the American people, and we want it back.”

The Hidden Agenda

On July 16, Democrats will gather in San Francisco to nominate their presidential candidate. Since leaving the vice presidency three and a half years ago, Walter Mondale has worked hard for that nomination. By all accounts, he will get it.

Through a torturously long and sometimes bitter contest, Mondale survived. He campaigned longer and harder than his opponents did. He raised and spent far more money than they did. Following a string of early defeats, Mondale’s awesome campaign organization managed to make him the front runner once again. It was, in all, a masterful performance.

Today one major controversy tarnishes that performance: the Mondale campaign’s creation of 135 “independent” delegate committees as a means of evading federal election law, which limits how much candidates may spend in total and in each primary. The committees were phony; their real purpose was not to elect Mondale delegates but to vacuum up money Mondale could not accept (from individuals who had already contributed the legal maximum) and money Mondale had promised he would not accept (from PACs).

Only after opponent Gary Hart had complained to the Federal Election Commission and the issue had turned into a political liability did Mondale’s organization shut down its delegate committees. First Mondale claimed the committees were entirely independent and beyond his control; then he said the flood of PAC money into the committees would stop; next he ordered that the committees be disbanded; and finally he agreed to count the committees’ spending against his own campaign ceiling and to give some of the money they had raised back to the contributors. “We will refund all contributions made to delegate committees,” Mondale said, “which would not have been acceptable if made to the campaign directly.”

Mondale hoped that would put an end to the issue, but it did not. Federal Election Commission records show that Mondale’s presidential campaign organization choreographed the operation, which included transfers of money and employees between the delegate committees and Mondale headquarters and a coordinated effort to defray the national campaign’s expenses in key primary states. Hart’s organization has charged that the scheme was illegal and is threatening to challenge at the Democratic National Convention the legitimacy of Mondale delegates elected with “tainted” funds.

Some saw the episode as nothing more than a mistake in the Mondale operation, an isolated case of expediency mattering more than ethics. In truth, however, it was business as usual.

From nearly the moment Mondale left the vice presidency, his top advisers set out to create a series of illusions — ingenious fictions about how he has made a living, how he has financed his political and business activities, and how faithfully he has followed the spirit and letter of the nation’s election laws. These efforts to hide the truth have been remarkably successful, granting Mondale an enormous advantage over his competitors and allowing him to virtually grasp the one thing he has wanted all along: the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination.

Mondale and his advisers created the Committee for the Future of America, whose purpose, they claimed, was to underwrite his travels across the nation on behalf of Democratic candidates. This has become par for the presidential course: plenty of other presumed and actual candidates (among them Ronald Reagan, Edward Kennedy, Howard Baker, and Robert Dole) have had similar PACs. So perhaps it should not surprise anyone that CFA was little more than a front for the maintenance of Mondale’s political machine.

Yet the secret side of the Committee for the Future of America was at sharp odds with the public posture of its chief spokesman and fundraiser. While Mondale decried the influence of special-interest money on American politics, his PAC sought out funds that would have been flatly illegal if contributed to a candidate for Congress — or, for that matter, the presidency. Moreover, his top advisers engaged in extraordinary efforts to keep their entire soft-money operation secret.

When Mondale’s PAC ran desperately short of money in 1982, only the forbearance of its major creditors — including Mondale’s law firm, Winston & Strawn — enabled it to make contributions to Democratic candidates for the November elections. And when CFA desperately needed money to settle these debts in 1983, Mondale’s friends and business associates came to its rescue. As a presidential candidate, Mondale voluntarily washed his hands of PAC money, claiming it corrupted the election process; at the same time, this unwelcome money was being used to pay off his own PAC’s creditors.

Even what seems to be the closing chapter in the story of Mondale’s PAC — the disposal of its 25,000-name fundraising list — is shrouded in secrecy. Mondale’s advisers have publicly said that the buyer is a California mailing list broker, which, as far as it goes, may be true. What they have never publicly disclosed, however, is that someone else, whose identity they claim not to know, actually owns the list and has regularly profited from renting it to others, including Mondale’s presidential campaign committee.

Secrecy is the principal evil — some say the only evil — in the financing of political campaigns. It has been the wellspring of famous scandals from Teapot Dome to Watergate and the inspiration for campaign finance laws that are intended to close the loopholes and promote public disclosure of the sources and uses of funds. When candidates and committees faithfully obey the laws, the public can draw a clear picture of how political money is raised and spent.

Secrecy has been so central to Mondale’s political operation, however, that an accurate picture is impossible to obtain. His advisers refuse to discuss the soft-money operation they began in 1981 other than to reluctantly confirm that it existed. They say the facts surrounding CFA’s repayments to Mondale’s law firm are nobody’s business but their own. They even decline to provide details about Mondale’s questionable treatment of his income and tax deductions as a self-employed businessman.

During a televised debate with opponents Gary Hart and Jesse Jackson on June 3, 1984, two days before the last round of presidential primaries, Mondale defended his handling of the controversy surrounding the Mondale delegate committees. “I’ve gone clear beyond anything that was necessary,” he said, “because I want not just to comply with the law — I want to demonstrate an ethical standard, a sense of personal responsibility, that goes beyond what is needed.”

Mondale’s Political Expense Account

From the beginning, the Committee for the Future of America was, in many respects, Walter Mondale’s political expense account. Formed just 14 days after he left the vice presidency, CFA was the mechanism for raising the millions of dollars that would allow Mondale, as a noncandidate, to do everything he would later do as a candidate.

From the outset, Mondale’s advisers claimed that CFA was not a presidential campaign-in-waiting. “This is not a Mondale campaign operation,” aide Michael Berman said in 1981. “We see this as a means of getting good Democrats elected.”

Presidential campaigns have gotten so expensive and the nomination process so protracted that undeclared candidates need PACs to gain an early edge. The Committee for the Future of America gave Mondale at least a $2.5 million head start over his opponents (money that would not count toward his spending ceiling as a declared presidential candidate), a ready-made mailing list of sympathetic souls, and an experienced staff whose loyalty had been cemented by two years on his political payroll. Moreover, Mondale’s PAC allowed him to collect valuable IOUs that could be redeemed the moment he actually became a presidential candidate.

Mondale’s PAC also served as a holding pen for the individuals and consulting firms that would run the official phase of his presidential campaign. And it allowed longtime financial backers who didn’t have the means to retain Mondale as a corporate director or consultant to help in smaller but nonetheless significant ways.

The Committee for the Future of America’s operations were split between two Washington law firms. Grove, Engelberg & Gross rented CFA space for its official headquarters, although it amounted to little more than a mailing address and desk space for employees outside of Mondale’s inner circle.

The real command center was four blocks away at 2550 M Street, N.W, in the Washington office of Winston & Strawn, Mondale’s law firm. A small battalion of Mondale operatives worked there, as did James Johnson, Mondale’s-chief political strategist, who had set up his own consulting firm, Public Strategies, on the premises.

Winston & Strawn was, in effect, the corporate headquarters of “Mondale, Inc.,” a term Johnson had coined to describe the former vice president’s varied business and political roles: lawyer, speaker, writer, corporate director and consultant, chief spokesman and fundraiser for the Committee for the Future of America, and undeclared presidential candidate.

Within little more than a year, Mondale’s PAC had evolved into a burgeoning operation. By August 1982 it had raised $1,755,113 and contributed $89,750 in direct contributions to Democratic congressional candidates, and it was carrying 19 employees on its payroll. Yet the PAC’s apparent financial condition, as reported to the Federal Election Commission and re-reported by newspapers all over the nation, masked its real problems.

Although CFA had plenty of cash in the bank, huge undisclosed debts —$134,477 in all — left it with $22,419 in red ink at the end of August — a time when it was gearing up, supposedly, to pump financial assistance into key Democratic races.

The flow of soft money into the PAC’s treasury, however, helped it to meet its considerable day-to-day operating expenses. In August 1982 alone, soft-money solicitations brought in $5,000 from the Service Employees International Union in Washington, D.C.; $5,000 from the Central Produce & Equipment Company in Duluth, Minnesota; $5,000 from Archer-Daniels-Midland Company in Decatur, Illinois, which is run by Minnesota farmer/businessman Dwayne Andreas; $3,000 from Wexler & Associates in Washington, D.C., a consulting firm run by Anne Wexler (who was also a CFA board member); and a variety of other contributions from corporations and unions.

Other soft-money checks came from Burger King Corporation in Miami; Carl Byoir & Associates, a New York public relations firm; the Jerome L. Greene Foundation, Abbott Industries, and Lily of France Marketing, lnc., all in New York; the Newark and San Francisco offices of Touche Ross & Company, an accounting firm; Davis Oil Company in Denver; and District Photo, Inc., in suburban Washington, D.C.

Virtually every expense the PAC incurred, from long-distance telephone service to a UPI machine for election night 1982, could be split in some way — paid partly with hard money and partly with soft money. Some of the PAC’s soft money went to Public Strategies, Johnson’s consulting firm, for part-time secretarial service; to Johnson and Berman, for miscellaneous expense reimbursements; and to Berman’s Washington law firm, Kirkpatrick, Lockhart, Hill, Christopher & Phillips, for “administrative costs.”

This enormously complex apportioning scheme was regulated by Berman, who frequently summoned file folders of bills to his office so that they could be prorated and paid. The centralization of this operation, not coincidentally, accommodated the need for secrecy.

Of the money that Mondale’s PAC reported to the Federal Election Commission, very little found its way into congressional candidates’ campaign treasuries. Of the $2.5 million it raised through the end of 1983, only $136,880 went in direct contributions to Democratic House and Senate candidates. Mondale aides defend this ratio — roughly five cents of every dollar raised — by pointing to the high cost of raising money. CFA also reported nearly $92,000 in in-kind campaign contributions, which usually amounted to apportioning the cost of airline tickets and hotel bills for Mondale and his staff. Nearly two-thirds of the PAC’s spending for travel apparently had little to do with helping candidates: at least $139,330 was not allocated to any campaign.

In many cases, the Committee for the Future of America’s ostensible business — “getting good Democrats elected” — was secondary to getting one good Democrat elected. The real campaign, of course, was Mondale’s. In January 1982, for example, CFA picked up the tab for a three-day conference at the Wye Plantation on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, at which more than a hundred Mondale supporters received strategy briefings. The PAC’s newsletter, which was mailed to all contributors, regularly published such features as “A Message from Walter Mondale,” “Excerpts from Mondale Speeches,” and “Mondale on the Issues.” During Labor Day weekend in 1982, the PAC spent at least $75,000 — plus an unknown amount of soft money —so that Mondale could give nationwide radio addresses on such topics as Reaganomics, arms control, jobs, and “the future.” CFA funds were even used to pay for Mondale’s meetings at Minnesota fishing resorts.

Many major contributors to Mondale’s PAC were clearly interested in something more than helpings Democratic congressional candidates; they were interested in enhancing Mondale’s prospects for winning the Democratic presidential nomination. Of the PAC’s 744 contributors of $500 or more, 380 — more than half — had also given the Mondale for President Committee at least $500 through early 1984. Only seven of those 744 contributors — less than 1 percent — had given Gary Hart’s presidential campaign $500 or more. None of them had made major contributions to Jesse Jackson’s campaign

A few months after Mondale’s presidential campaign committee began raising its own money, the Committee for the Future of America would become, for all practical purposes, a thing of the past.

Mondale, Inc.’s Corporate Offices

As Walter Mondale crisscrossed the nation in 1982, campaigning for Democratic candidates and earning money from speaking engagements and consulting contracts, the partners at Winston & Strawn avoided what seemed to be an inevitable confrontation. No ultimatums had been issued; instead, the delicate chores of diplomacy had been assumed by John Reilly, a senior partner in the Washington office of Chicago’s oldest law firm.

More than a year earlier Reilly had arranged for Mondale, his friend of 20 years, to join Winston & Strawn. He had even relinquished his corner office, the firm’s biggest, to make way for the former vice president. (This year Mondale has entrusted Reilly with the important job of searching for and screening potential running mates.)

As Winston & Strawn’s “rainmaker,” Mondale was to attract new clients, not practice law. He was paid $150,000 a year, provided with a chauffeur and a car, and allowed to place a number of his own aides on the law firm’s payroll. As part of the deal, Winston & Strawn also permitted Mondale’s top strategist, James Johnson, to set up a consulting business, Pubic Strategies, in its offices.

At the outset, in early 1981, everyone seemed happy with the arrangement. Over the next two years, however, the tensions within Winston & Strawn were, at times, palpable. As the firm’s lawyers were shifted around to make way for a growing contingent of Mondale operatives, inconveniences became irritations. Reilly once again gave up his office, this time for Johnson. After the move, Johnson’s office was down the hall from Mondale’s separated only by one of Winston & Strawn’s conference rooms. Soon, however, to allow Johnson private access to Mondale, a crew of workmen cut doors in both ends of the conference room.

Although Mondale spent most of his time away from Winston & Strawn, the law firm’s offices were supporting, financially and otherwise, his rapidly expanding organization. Winston & Strawn’s partners found that some people on their payroll whose attentions were commanded by Mondale’s needs had little time for the firm’s work. By mid-1982, in fact, an entire side of Winston & Strawn’s fifth-floor office had become known inside the firm as the Mondale Wing.

Trying to make the best of the situation, Reilly found himself soothing bruised egos and patching up problems. Everyone acknowledged that if Mondale were elected president in 1984 his association with Winston & Strawn would lend a nice sheen to the firm’s image — and presumably to its long-term profit picture as well.

But Winston & Strawn’s senior partners, surveying the firm’s performance in 1981, knew the bottom line: Mondale had not brought in a single new client. As a consequence, they zeroed in on a pressing business matter: the former vice president had become a growing financial drain on the firm.

Although the situation at Winston & Strawn was carefully hidden from outsiders, the Mondale operation’s spending had gone far beyond anyone’s control. An internal accounting system had been put in place to keep track of expenses attributable to any of several activities unrelated to the firm’s business: Mondale’s personal affairs; Mondale’s own business pursuits; Mondale’s PAC, the Committee for the Future of America; and Johnson’s consulting firm, Public Strategies.

The accounting system, basically a collection of log books, broke down. Although the firm’s lawyers methodically kept track of their long-distance calls and photocopies so the expenses could be billed to clients, for example, no such discipline was practiced by those in the Mondale Wing. In one attempt to impose that discipline, Winston & Strawn installed electronic meters on its photocopying equipment so that it could not be used without a preassigned billing code.

From early on, some Winston & Strawn employees worked exclusively on Mondale’s business and political affairs. As the legal and financial implications of this arrangement became clear, however, some employees began moving, in musical-chairs fashion, to different payrolls. Over the course of a single year, a Mondale worker might draw paychecks from Winston & Strawn, Mondale himself, Mondale’s PAC, Mondale’s presidential campaign committee, and Public Strategies.

The sheer volume of activity was an accountant’s nightmare; it was frequently impossible to reconstruct who within the Mondale operation had spent what on whose behalf. One thing, however, was clear: CFA was responsible for most of the debts. As negotiations continued over how much and how soon Winston & Strawn would be repaid for everything, one problem precluded a speedy resolution: Mondale’s PAC had been deeply in debt throughout late 1982, sometimes by as much as $150,000.

In 1981 Winston & Strawn received a total of $5,913 in reimbursements from Mondale’s PAC; by the end of 1982 it had been repaid $11,703 more, $5,000 of it on December 30. Then, beginning in February 1983, the trickle turned into a flood tide: CFA’s reports to the Federal Election Commission show successive payments in early 1983 of $5,000, $5,000, $4,636, $20,000; $10,000, and $10,000. All of these repayments, according to Berman, reflected costs advanced by Winston & Strawn in 1981 and 1982. (A remaining debt to Winston & Stawn of $5,926 had not been paid as of March 1984.)

By the end of 1983 Winston & Strawn had recovered $245,119 from Mondale’s PAC, Mondale’s presidential campaign committee, and Mondale himself. The money represented repayments to the law firm for everything from airline tickets to the salary of Mondale’s chauffeur. Most of these payments were disclosed publicly. Other payments, including at least $19,234 that had come from one or more of Mondale’s soft-money accounts, have never been made public.

Mondale’s exploitation of his employer, Winston & Strawn, poses serious ethical and legal questions. In essence, he used its resources to underwrite the expenses of a massive political operation at times his PAC could not afford to pay them on its own. After the Winston & Strawn partners complained about the magnitude and the legal implications of what was going on, Mondale’s advisers acknowledged the debts by having CFA repay the law firm more than $54,000 in hard money during 1983 — but only after nearly all of its other creditors had been satisfied.

As a consequence, for nearly two years Mondale’s PAC grossly underreported to the Federal Election Commission its true financial obligations to Winston & Strawn. Under federal election law Winston & Strawn was required to have been paid “within a commercially reasonable time in the amount of the normal and usual rental charge.” From the limited records made available to us by Mondale’s PAC, it is clear that did not happen.

The Committee for the Future of America was not a client of Winston & Strawn. The law firm did not profit from its relationship with CFA as it did from its other business relationships. When Winston & Strawn was finally compensated for the use of its resources — “something of value,” which is the same as money under federal election law — it received no interest. (In some cases, two years may have elapsed between the time Winston & Shawn incurred the costs and the time it was repaid.) As a result, Mondale’s advisers, in all likelihood, thrust his law firm into the position of unwittingly making unreported, and therefore illegal, contributions to his PAC.

The Master Plan

Sometime before the polls had even closed on Tuesday, November 2, I982, an account was opened at D.C. National Bank through which Walter Mondale’s 1984 presidential campaign would be financed. Over the next two months the Mondale machine would prepare for the official launch of his candidacy — raising money, hiring staff, directing consultants — according to a detailed master plan maintained by James Johnson, Mondale’s most trusted adviser.

On January 3, 1983 — two days after contributions to his campaign became eligible for federal matching funds — Mondale’s presidential committee officially registered with the Federal Election Commission. Before that date — while Mondale was still raising money, traveling, and acting as spokesman for his PAC — he was careful, for the record, not to make up his mind about whether to run. “I did everything consistent with the law, which is that I was not a candidate,” Mondale told a reporter for the Washington Post. “I was helping congressional candidates. I was very careful both never to say anything different and believe anything different.”

No one at Winston & Strawn, however, could have had any doubts about Mondale’s intention to run. There, employees of Mondale’s PAC worked alongside employees of Mondale’s “testing the waters” committee, which was soon renamed the Mondale for President Committee. Some of the exploratory committee’s expenses were even charged to Mondale’s law firm. From the outside, the PAC and the presidential committee may have appeared to be separate; from the inside, they were indistinguishable.

As soon as there was enough money to do it, Johnson began hiring staff for the presidential committee. He did not have to look far. Eight of the first nine people he hired were drawn from the payroll of the Committee for the Future of America. Mondale’s PAC had 17 employees on Election Day, 1982; 14 of them were eventually shifted to the Mondale for President Committee. The migration was so methodical, in fact, that most did not miss a single day between paychecks.

More than a dozen consultants and suppliers were paid by Mondale’s PAC and his presidential committee simultaneously, making it virtually impossible to tell where and how any lines were drawn between their respective activities. Many times, in fact, there were no lines.

Even before Mondale announced his candidacy, for example, his top advisers planned the presidential campaign’s secret use of the PAC’s 25,000-name contributor list, which had been compiled over two years at a cost of nearly $1 million. To keep it secret, they routed payments through Targeted Communications Corporation, a direct-mail consulting firm based in Falls Church, Virginia. Because Targeted Communications had been retained by both Mondale’s PAC (the “left hand”) and his presidential committee (the “right hand”), it was the ideal conduit for shielding financial handshakes from public view.

Even though the Mondale for President Committee used the PAC’s fundraising list in early 1983, there was no way for outsiders to know it. In its report to the Federal Election Commission for the last half of 1983, Mondale’s PAC showed an undated payment of $2,002 from Targeted Communications that it described as “direct mail list income.” It made no reference at all to the Mondale for President Committee.

Why the need for such secrecy? The answer would be obvious only to those versed in the intricacies of the Federal Election Campaign Act, which says that if political committees act in “cooperation, consultation, or concert” their independent status may be endangered. If Mondale’s PAC and his presidential committee were deemed to be affiliated, all of their contributions and expenditures would be brought under a single umbrella.

The consequences of such affiliation, theoretically, could be enormous: at least $905,182,and perhaps much more — the total amount by which 444 individual donors to both committees exceeded the $1,000 limit for contributions to presidential campaigns — might have to be counted against Mondale’s spending ceiling; in certain circumstances, the excess funds might even have to be returned to the contributors. (This amount, of course, does not include the contributions raised by CFA’s covert affiliates.)

Federal election law also holds that political committees “established, financed, maintained, or controlled by the same person or group of persons are affiliated.” For this reason, Mondale’s advisers were careful, on paper, to preserve the illusion of separation: there were two sets of incorporation papers, two sets of books, two sets of officers. In fact, however, Mondale’s advisers controlled both committees. Michael Berman, the treasurer of the Mondale for President Committee, performed precisely the same duties for the Committee for the Future of America. Berman’s denial of this role is tempered by his admission that the PAC’s financial reports to the Federal Election Commission were prepared in his law firm’s office, at least from early 1983 on, by a “volunteer” who, he says, had nowhere else to work.

The “volunteer” was Elizabeth Brittain, a full-time employee of the Mondale for President Committee. Brittain even signed some of the PAC’s reports to the Federal Election Commission, and at least one of them was run through the postage meter at the presidential committee’s headquarters.

By the time Mondale made his presidential ambitions official, not much was left of the Committee for the Future of America. The PAC’s staff had dwindled to three, all of whom would soon move over to the cash-heavy presidential committee’s payroll. The charade, in short, was over.

For yet another month, however, Mondale’s advisers continued to promote CFA as a potential force in the 1983 and 1984 elections. The motivation for this deception was not optimism, but need. Though its real financial condition had been carefully masked during the 1982 elections, when it might have caused some political embarrassment, Mondale’s PAC was still deeply mired in debt at the beginning of 1983. Its biggest debt, in fact, was to Mondale’s employer.

CFA once again turned to direct mail fundraising. In late January 1983 Gerry Sikorski, a newly elected Democratic congressman from Minnesota, appealed by mail to CFA’s financial supporters. (Mondale, who had signed all of the PAC’s previous solicitations, could no longer lend his name to them without risking a determination that his committees were affiliated under federal election law.) Sikorski implored them to “defeat the New Right in the 1983 elections (in Louisiana, Mississippi, Kentucky, Philadelphia, Boston, etc.) and prepare for the elections so that we can purge extremist, right-wing politics out of the American system.”

Sikorski’s letter continued: “That is why I ask you to please renew your special financial support for CFA today. We must begin 1983 as involved in shaping new policies as we were in rejecting the old. CFA must help pioneer a new role of political cooperation between the government and the people.”

Just days after its contributors received this urgent appeal — before most had even found time to respond to it — Mondale’s advisers decided to shut down the PAC for good. This development paralleled a dramatic change in the PAC’s publicly reported financial condition. On January 31, 1983, $45,138 in previously unreported debts from 1981 and 1982 appeared on the PAC’s records at the Federal Election Commission. Over the next two days CFA amended each of the first 10 reports it had filed with the Federal Election Commission, revealing, in the process, that it had failed to disclose — or had improperly disclosed — debts dating from as far back as the first half of 1981.

Most of the previously undisclosed debts were to Presidential Airways, a charter aircraft company. The line of credit apparently extended to Mondale’s PAC in 1982 ranged from $23,525 to $45,572; through the end of that year, in fact, the Committee for the Future of America had paid Presidential Airways only $8,268 for charter airline flights billed at $53,841. The enormous balance on the PAC’s invoices, which it finally paid between February and May 1983, apparently included no interest charges or late payment penalties. (Some of the PAC’s soft money was channeled to the company; how much is unknown.) Employees of Presidential Airways refuse to discuss these matters or any others that pertain to Mondale’s PAC.

The PAC’s two major debts, to Winston & Strawn and Presidential Airways, were almost completely retired in the first half of 1983, as Mondale’s presidential campaign hit full stride. CFA managed to raise $253,308 in hard money during this period, 88 percent of it in amounts of $1,000 or more. Twenty-six individuals and nine other PACs gave the legal maximum of $5,000 each, accounting for $175,000 in contributions — more than two-thirds of CFA’s total intake.

More than $43,000 steamed into Mondale’s PAC even after its last employee, executive director Curtis Wiley, resigned, on March 31, 1983. (Wiley joined the Mondale for President Committee the following day.) A handful of Mondale’s well-heeled friends and business associates helped to bail out his PAC, allowing it to repay almost all of its debts to his employer. New York investment bankers Herbert Allen and Herbert Allen, Jr., for example, each gave Mondale’s PAC $5,000 on March 10; at the

Time, Mondale was still on the payroll of their firm, Allen & Company. Chicago businessman Irving B. Harris and his wife each gave Mondale’s PAC $5,000 on May 3. Harris was a generous friend: he had previously donated huge sums to Family Focus, a Chicago-based nonprofit group, earmarking the money to help pay $100,000 in consulting fees to Mondale and at least $50,000 to Public Strategies.

Michael Berman says Mondale did nothing during this period to help raise funds for his debt-ridden PAC. Among the documents he provided us is a legal memorandum claiming that since January 2, 1983, “Mr. Mondale has not acted on CFA’s behalf in any capacity — he has not raised funds, traveled, or acted as spokesman.” Who, then, raised the money?

Berman’s answer: “Volunteers.”

Secret Transaction

Today, if anyone asks questions about these activities — indeed, asks anything at all about the Committee for the Future of America — the PAC’s officers do not wish to answer them. Washington lawyer Lynda S. Mounts, the PAC’s general counsel and corporate secretary, says she does not even know who has custody of its books. Although Mounts also says she does not know how to reach CFA’s president and treasurer, David Phelps, his business telephones ring within the quarters of Cadwalader, Wickersham & Taft, the law firm in which she works. Phelps does not respond to telephone inquiries about CFA’s business. Apparently, his role for the PAC was to sign three of its Federal Election Commission reports.

One question nobody will answer is, what happened to the computerized fundraising list of Mondale’s PAC? Political mailing lists, because they can be rented to others for $50 and up per 1,000 names, can be exceedingly valuable properties. CFA’s mailing list of 25,000 contributors, in fact, was its only asset with income-generating potential.

The mailing list mystery is a prime example of how Mondale’s advisers sought to use election law loopholes as a smokescreen for transfers of large amounts of money. Only this much is certain: On April 22,1983, Mondale’s PAC deposited a $23,233 check from Names in the News, a San Francisco mailing list broker. The payment was for what CFA described as a “direct mail list purchase.”

Was it?

“I really can’t discuss it,” says Elaine Murphy, a vice president of Names in the News. “All of our transactions are totally confidential.”

Readers of CFA’s disclosure reports to the Federal Election Commission might conclude that Names in the News had purchased the contributor list. Murphy, however, says her company has never owned the PAC’s list but is simply a broker for those who wish to rent it. Who, then, does own the list?

“We’re not in a position to divulge that,” Murphy says. Michael Berman says he does not know. Curtis Wiley, the former executive director of Mondale’s PAC, says he does not know.

Even the person who apparently negotiated the transaction, Robert Smith, the president of Targeted Communications Corporation, claims he does not know. “Names in the News specifically requested that the purchaser be kept confidential,” he says. Smith does not explain why he would be asked to keep secret something he does not know.

Soon after the $23,233 transaction was completed, Names in the News began renting the Mondale mailing list under a different name (PAC Donors). Mondale’s advisers clearly wanted to hide the fact that his PAC’s contributor list was, for the first time ever, on the industry’s rental market — in short, that someone was making money every time it was used. An April 14, 1983, letter to Names in the News noted: “We would make only one request — that the origin of the list not be revealed. It is our understanding the list will be renamed and may be referred to as a ‘PAC donor file’ but a specific name will not be used.”

Sweetheart Deals

Walter Mondale has never been a wealthy man.

“When I left office after 22 years, not counting our house we had a net worth of $15,000,” he told a reporter in 1981. “And I’ve had to lie about the [value of our] furniture to get the figure up to that.” Since then Mondale has done quite well for himself. He, in fact, was the most successful subsidiary of Mondale, Inc.

After leaving the vice presidency, Mondale methodically exploited the enthusiasm of others — long-time political supporters, for the most part — to hire him and his aides for what amounted to make-believe jobs. At Winston & Strawn, for example, Mondale has been paid more than $12,000 a month for assignments neither he nor his employer have been willing to discuss.

The Winston & Strawn arrangement was not Mondale’s only sweetheart deal. From 1981 to 1983 he collected more than $469,381 in fees as a corporate director and consultant. Family Focus, the Chicago-based nonprofit group that helps teenage parents, hired Mondale in 1981 and 1982, at $50,000 a year, to help with its fundraising. The impetus for this contract, as well as the money, came from Irving B. Harris and Bernard Weissbourd, two wealthy Chicago businessmen, whose families channeled an additional $31,250 into Mondale’s PAC. Ultimately, Mondale raised no money for Family Focus; his efforts in 1982 were limited to touring one of its centers and attending an advisory committee meeting.

Northwest Energy Company, which built the Alaska pipeline, paid Mondale $43,750 in 1981; its chairman, John G. McMillian, also gave CFA $5,000, the legal limit, the same year. This is one case in which Mondale confirmed, more or less, that he got paid for doing little or no work: he admitted that his only task consisted of finding out, with a single telephone call, when a congressional hearing was scheduled.

Investment banker Herbert Allen has been Mondale’s most generous benefactor. As the chairman of Columbia Pictures Industries, he arranged for Mondale to receive $103,773 in fees. When Columbia was acquired by Coca-Cola, he found another niche for the former vice president at Allen & Company, his New York investment banking firm, which paid Mondale $56,250. Allen and his son, Herbert Allen, Jr., also helped defray Mondale’s political expenses; in 1982 and 1983 they gave at least $15,000 to his PAC.

Mondale also collected more than $303,000 from 1981 to 1983 as a self-employed lecturer and writer. His fees ranged from $150 for an article in the Los Angeles Times to $22,000 from the Borsen Corporation of Denmark for three speeches (at $14,000 per) on March 15, 16, and 17, 1983, in Amsterdam, Copenhagen, and Helsinki.

These arrangements gave Mondale the financial freedom to devote virtually all of his energies, from 1981 on, to his real business: running for president.

Mondale has said he was able to draw a clear line between his business and political activities. “I have been punctiliously careful to separate the two,” he told a Washington Post reporter in late 1983. “I wanted it that way. You can’t have private funds paying for political activities.”

It seems certain, however, that private funds were sometimes used to pay for Mondale’s political activities and that political funds were sometimes used to pay for private activities — in short, that no one in the Mondale organization, including Mondale, carefully kept the two separate.

In fact, Mondale the politician was often indistinguishable from Mondale the businessman, at least in his reports to the Internal Revenue Service. A close examination of the income he reported and the tax deductions he claimed as a self-employed businessman shows the degree to which Mondale allowed these separate roles to blend together.

For example, Mondale listed $14,812 in “travel reimbursements” as income on his 1983 tax return. In response to a request for more information, Michael Berman provided a breakdown of Mondale’s travel-related income and expenses for that year that showed, among others, payments from the National Education Association ($4,297); the American Society of Newspaper Editors ($2,239); the Springhill Conference Center in Orono, Minnesota ($1,450); the Sheet Metal Workers union ($1,356); the American Council on Education ($985); the Southern Christian Leadership Conference ($730); the Kentucky Democratic Party ($694); and the American Federation of Government Employees ($204). The list does not contain any travel-related deductions — expenses Mondale paid himself — that clearly correspond to these reimbursements.

To establish that Mondale did not profit personally from any of the reimbursements — although doing so would not violate the Internal Revenue Code provided they were declared as income — we asked Berman to show that Mondale had paid the underlying expenses himself. Berman refused; he says an implication that Mondale billed organizations for expenses he did not pay is “absolutely false.”

Some of the organizations Mondale billed, including the National Education Association, the Kentucky Democratic Party, and the Sheet Metal Workers, were unable to find any record of having made travel reimbursements to him in 1983. Others were able to locate such records.

Mondale spoke, for example, at the annual convention of the American Society of Newspaper Editors in Chicago on May 7, 1982. Nearly a year later ASNE received a memo from Mondale’s office requesting a payment of $2,329 for his air fare. When ASNE asked for a breakdown or invoice, Mondale’s office sent it a photocopy of a bill for $4,658 from Presidential Airways to CFA. Accompanying it was the explanation that ASNE was being asked to pay half of the cost of the chartered jet. ASNE was instructed to make its check payable to the “Walter F. Mondale Special Account,” whose mailing address was Berman’s law office.

Mondale’s official travel schedule shows no CFA events immediately before or after his ASNE appearance. While another group was presumably asked to pay the other half of CFA’s bill from Presidential Airways, no similar reimbursement appears on the list Berman provided. (Presidential Airways will not say when or by whom its bill to Mondale’s PAC was paid.)

The blurring of Mondale’s political and business activities is also reflected in his deductions for payments to his own consultants and employees from 1981 to 1983. In each of his first two years as a self-employed businessman, Mondale collected roughly the same amount in fees: $329,077 in 1981 and $334,768 in 1982. He claimed $30,111 in tax deductions for payments to his employees and consultants in 1981, or 9.2 percent of his total fee income for the year. In 1982, a year of intensive political activity for Mondale’s PAC, his payments more than doubled — to $74,864, or 22.4 percent of his fee income. (Of the 12 people Mondale paid during 1982, eight also received money from his PAC.)

As a presidential candidate in 1983, Mondale still managed to collect $128,500 in fees. But his tax deductions for payments to his employees and consultants dropped to only $4,738, representing the part-time services of a single bookkeeper, or only 3.7 percent of his fee income for the year. Because the expenses Mondale incurred in generating outside income — the cost of business correspondence, scheduling, and so on — vanished entirely in 1983, an obvious question arises: Were employees of his presidential committee doing work for him?

Another significant change in Mondale’s finances took place in 1982: He began paying Winston & Strawn an “administrative office charge” and deducting it on his tax return. Berman says the charge represented $17,532 in reimbursements for telephone and secretarial service, travel, taxicabs, photocopying, deliveries, and miscellaneous expenses. Berman is at a loss to explain why Mondale incurred no such “administrative office charge” at Winston & Strawn the year before.

Additional questions are raised by a comparison of Mondale’s tax returns to the financial disclosure statements that he is required to file with the Federal Election Commission under the Ethics in Government Act. For example, Mondale reported receiving $128,566 in fees on his 1983 tax return; his financial disclosure statement, however, lists only $116,381 in fees, which, by law, must be itemized.

The $12,185 difference can be traced to a discrepancy in Mondale’s disclosure of payments he received from Winston & Strawn in 1983: he reported $150,020 in “wages” on his tax return, $162,205 in “salary” on his financial disclosure statement. The gap has only two possible explanations: either Mondale made an accounting error or Winston & Strawn acted as a conduit for his speaking, writing, and consulting fees. Berman declines to clarify the matter.

These practices raise serious questions for which there may be simple answers. If there are, however, the Mondale campaign does not seem able to provide them.

The Public’s Right To Know

Nearly 11 years ago, on September 18, 1973, Democratic Senator Walter F. Mondale of Minnesota appeared before the Senate Committee on Rules and Administration to urge passage of legislation that would provide public financing for presidential elections.

“The present system almost gives an irresistible, incentive to get around the law, and everybody knows it,” Mondale said. “Every politician wants to get elected. If a law is so restrictive that they cannot get the money, they cannot get it honestly — they will be attempting to do it in another way.”

“What we need,” Mondale said, “is a system that will permit public leaders to be honest if they choose to be honest.”

Today we have that system. In response to a Watergate-inspired wave of public outrage over secret money and its insidious influence on government, Congress cleaned up and opened up the financing of presidential election campaigns. It adopted, in modified form, Mondale’s proposal for granting presidential contenders federal matching funds based on their ability to raise small amounts of money from large numbers of contributors.

But the sweeping reforms in campaign finance laws have been eroded because some politicians seek ways to bend them, or even break them, for their own benefit. Mondale, despite his assertions to the contrary, is one of those politicians.

The conduct of a lesser force in the 1984 Democratic presidential campaign, former Florida governor Reubin Askew, provides a small but significant illustration of how politics can be something other than business as usual.

Askew eschewed the pre-presidential campaign PAC approach. The money he raised through 1982 to test the presidential waters, $363,767 in all, was counted against the ceiling imposed by law for each candidate. Why not an Askew PAC? “It could be argued that it is a circumvention of the spirit, although not the letter, of the federal election law,” an Askew spokesman said in mid-1982. “We decided to do it this way because he believes it is the right way to do it.” When Askew and his aides went to the 1982 Democratic National Party Conference in Philadelphia, his exploratory committee paid the bills, reported them to the Federal Election Commission, and later counted the expenditures against his presidential campaign spending ceiling.

When Mondale and his entourage went to the same midterm party convention, the Committee for the Future of America paid the bills, including expenses for telephone banks, hospitality suites, and catered receptions. The expenditures were not counted against Mondale’s presidential campaign spending ceiling because he had taken the precaution of claiming not to have made up his mind whether to even seek the Democratic nomination.

Some of Mondale’s other convention expenses were paid with funds from one or more of his soft-money accounts, into which otherwise illegal contributions flowed in unknown amounts.

Mondale had no legal obligation to reveal them to the Federal Election Commission, and he did not avail himself of any ethical obligation that might exist — in the spirit, say, of the public’s right to know — to fully disclose his political finances.

If Mondale does not believe in clandestine bank accounts for political funds, secret sales of mailing lists, and hiding important details of his personal finances, the bold leadership he promises the nation fails to move even his own advisers.

Mondale’s professed concern about the influence of special-interest money on American politics, which was at the center of his presidential agenda, has acquired a somewhat hollow, if not hypocritical, ring. Any further Mondale call for reform in this regard is not likely to inspire an already cynical public.

In his 1983 artcle on the Mondale political machine, “The Perpetual Campaign,” the Atlantic Monthly’s Gregg Easterbrook recounted a conversation with Mondale about the Committee for the Future of America: “When I asked him about his own PAC, Mondale became testy. ‘I’m just doing what the other guy is doing,’ he said. ‘As long as the system exists, you have to use it.’ “

Sidebar: A Statement From CFA Regarding Mondale’s Activities

Bill Hogan and Alan Green write for The City Desk, a Washington magazine bureau. They received the 1983 Worth Bingham Prize for investigative reporting.

This article originally appeared in the July 1984 issue of Regardie’s.