Here’s Mud in Your Eye

The Empire Strikes Back. Upon returning from a trip to the United States in November 1930, British steel magnate Sir Arthur Balfour expressed his newly acquired disdain for the nation’s capital. “Washington, from being a very desirable place, has become a very undesirable place,” Balfour said. “The spirits supplied are awful and dangerous in themselves.”

Worse yet, the former British foreign secretary noted, “prices of all intoxicants are exorbitant.”

Department of Dry Humor. “There is as much chance of repealing the Eighteenth Amendment,” said its author, Senator Morris Sheppard of Texas, “as there is for a hummingbird to fly to the planet Mars with the Washington Monument tied to its tail.”

The Old Bootleggers’ Ball Trick. All of Washington’s plainclothes cops showed up for the Bootleggers’ Ball, along with a handful of gullible paying customers. While the police were thus diverted, bootleggers-in-absentia ran huge consignments of Baltimore and New Jersey liquor into Washington, whose highways were left largely unpatrolled.

Getting Down to Brass Tacks. The Senate Committee on the District of Columbia, as part of its 1932 hearings on proposed legislation to allow warrantless searches for bootleg liquor in Washington, heard from Rufus S. Lusk, representing the local “battalion” of the Crusaders, perhaps the most potent of the nationwide dry organizations. Lusk introduced a good bit of statistical evidence into the record, including his compilation of gin prices in the District.

But Republican Senator Robert D. Carey of Wyoming had something other than prices on his mind. “How is the quality?” he asked.

“Excellent, excellent,” Lusk replied, warming to the question. “The quality is good and the effect is delightful, so I hear.”

Thanks, but No Thanks. When Washington’s Organized Bible Class Association decided to help District police enforce Prohibition laws, one member resigned in protest.

“The organization, I consider, is a very fine one, if it sticks to its knitting,” said Merritt O. Chance, the association’s treasurer and a former D.C. postmaster. “But I do not believe it was ever organized to do any spying on the neighbors of its members.”

Counterfeit Congressmen. Sometime in the late twenties, Washington bootleggers began to equip their automobiles with license plates bearing the word “Congressional” on the time-tested theory that few police officers would have the effrontery to stop cars with official tags.

Their scam worked, and no one, apparently, was able to determine whether the tags had been diverted from legitimate channels or expertly faked.

“A Sodom of Suds.” That’s how Clinton N. Howard, the chairman of the pro-Prohibition National United Committee for Law Enforcement, described Washington in 1929 to a mass meeting of drys at Eastern Presbyterian Church.

“The capital city is seething in lawlessness and saturated with poison liquor,” Howard said, “dispensed by bootleggers operating openly under various aliases and sold in hundreds of places as sugar is sold in the grocery.”

Howard evidently was not pleased with the official response to his revelations.

“The police department is either incompetent,” he said two weeks later, “or deaf, dumb, and damned to the prevailing conditions of vice which infest the national capital.”

The Envelope, Please. When Washington police raided the Club Champlain on 13th Street, N.W., in late 1933, they were shocked upon opening the speakeasy’s safe: it contained seven official D.C. Jail envelopes, each with money inside.

The mystery was cleared up when an investigation disclosed that the chief clerk of the jail, Francis J. McDonald, had lost the envelopes while pattonizing the speakeasy one day on his way to Police Court.

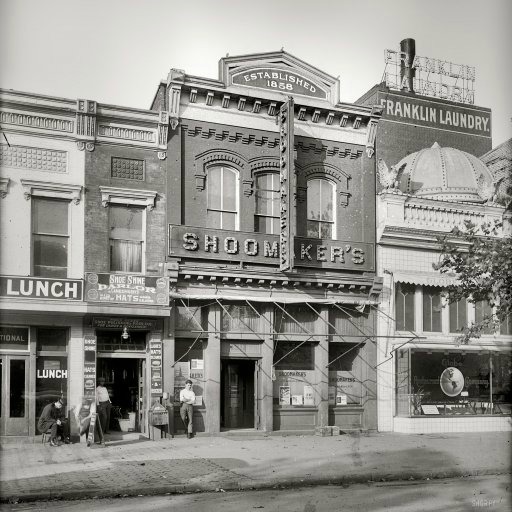

A Capital Cocktail. Colonel Joe Rickey, described by a Washington newspaper as a “celebrated lobbyist and general all-around good fellow,” was relaxing in Shoomaker’s saloon one pre-Prohibition day, as was his custom. Another patron, an out-of-towner, persisted in complaining about Washington’s abominable summertime heat. The colonel’s blood reached the boiling point.

“If this gentleman must be cooled off, he shall be cooled off, even if I have to do it myself,” announced Rickey.

He proceeded to improvise an antidote for the heat-stricken visitor: gin and lime juice (roughly three parts to one), crushed ice, and charged water. The recipient, so legend goes, pronounced it the finest beverage ever set before a human being.

Thus was born the Gin Rickey.

Investigative Journalism. In 1928 a Washington newspaper collected specimens of speakeasy beverages and took them to a laboratory for analysis. The lab successfully identified a sample of “Scotch” as 88-proof green rye with unknown, but apparently harmless, flavoring agents. It was stymied, however, by a highball of “Canadian Club” and ginger ale; as a subsequent report noted, “it had the strong smell of varnish and the potency of a kick from an army mule.”

Main Story: Days of Wine and Four Roses

This article originally appeared in the December/January 1984 issue of Regardie’s.