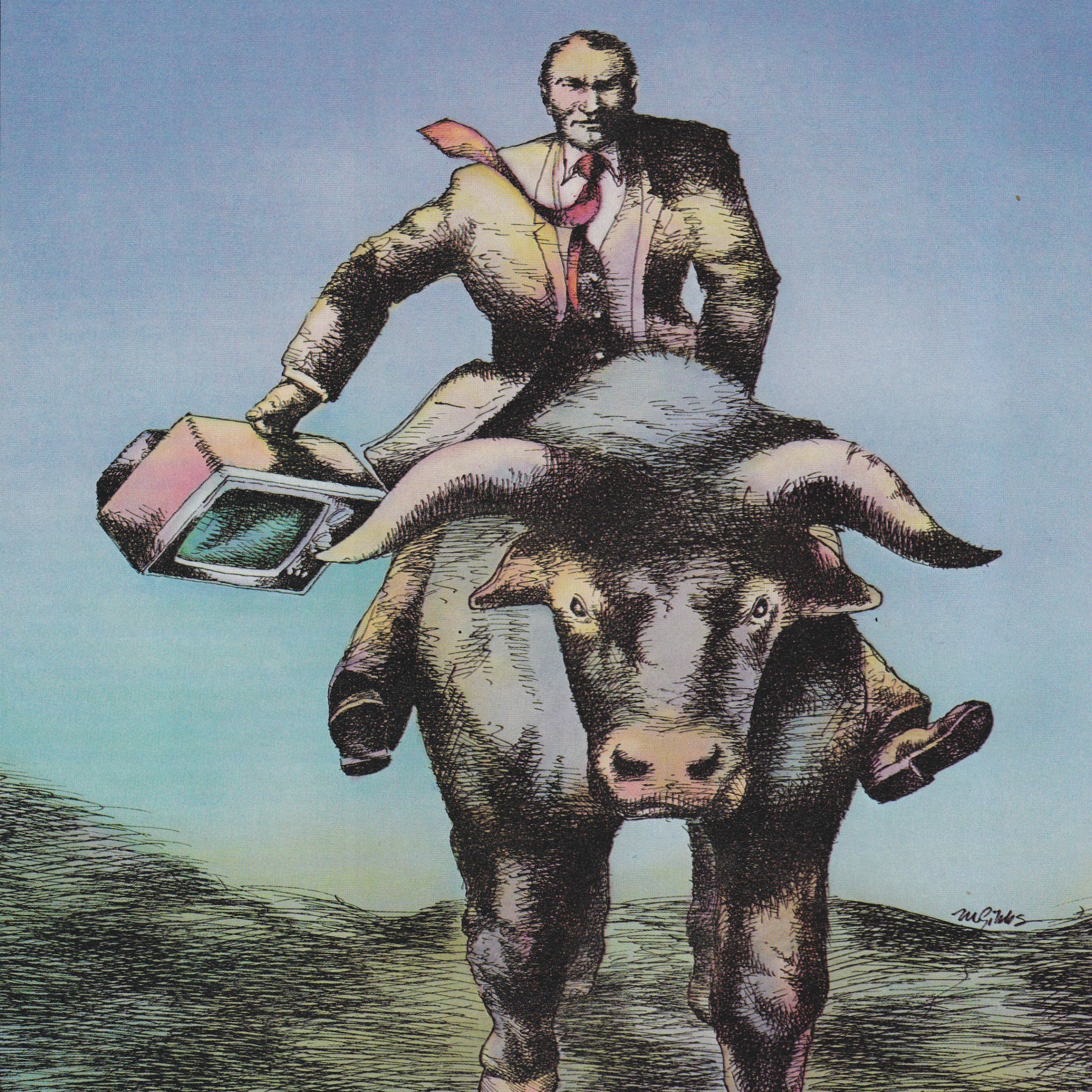

The Asset Test — Media Analysts Ride the New Bull Market

Washington Journalism Review

July 1985

Ken Berents, reporter-turned-handicapper, is on something of a roll. Lots of people with money want to know what’s on his mind these days — the inside dope, you might say — and the phones into his Baltimore office are busier than ever. “I’ve been on a hot streak,” he says. “I’ve been damn lucky, but I’m hanging my neck out right now.”

It is early in May, and Berents is preparing to hang his neck out, not on Skip Trial, Sparrowvon, Southern Sultan, or any of the other long-shot entrants in the 110th running of the Preakness Stakes at Pimlico, but on John Blair & Co., a New York firm with an enormous and expanding share of the junk-mail business. As a securities analyst for the Baltimore brokerage firm of Legg Mason, Berents picks media stocks — not horses — and he is betting right now that John Blair is going to be a winner.

“I’m the only guy on the Street who likes it, and I may be dead wrong, quite frankly,” Berents says. “Some publisher friend told me about it, and it’s causing the newspaper business fits.” The source of those fits is something called “ADVO-System,” a John Blair subsidiary that combines the advertising pieces of different companies — the kind typically sandwiched in newspapers, as inserts — and mails them (more efficiently and inexpensively) in a single batch. As a stand-alone company, ADVO-System’s revenues hit $183 million in 1983; John Blair acquired the company in 1984, and its revenues for that year topped $300 million. This year, the way Berents figures it, ADVO-System’s revenues might exceed $350 million, giving John Blair’s bottom line a handsome boost.

Last year, shares in John Blair traded on the New York Stock Exchange as low as 14½ and as high as 40. In May, as it trades in the $19 to $22 range, Berents likes the stock as a “speculative play” for Legg Mason clients — in other words, something short of what horse players call a mortal lock. A bargain? Time, and only time, will tell.

As a relative newcomer to what many view as a pressure-cooker profession, Berents fully appreciates what is at stake. “The thing is,” he says, “you live and die by what you recommend.”

While he awaits the market’s verdict on John Blair Co., Berents will be researching dozens of other stocks, writing about many of them, and recommending some of them to Legg Mason clients, which are, for the most part, retail, but also include banks, insurance companies, pension funds, investment advisers, and other institutional investors. Berents, a former economics reporter for the Baltimore Evening Sun, still covers a “beat”: He is assigned to the media industry — broadcasting, cable television, and publishing — a specialty shared by only 50 or so other securities analysts across the nation. Although most of these analysts work for big Wall Street investment houses, some, like Berents, profitably ply their trade at major regional firms.

For some time now, Berents and other media analysts have been finding themselves, along with the companies they cover, in the news as never before. A dizzying succession of acquisitions, mergers, leveraged buyouts, and takeover attempts — involving such big media companies as ABC, CBS, Metromedia, Capital Cities Communications, and Storer Communications — has made analysts who cover the industry nearly indispensable to journalists as sources of information and interpretation. These days, nearly any news account of the dramatic deals and other financial goings-on in the media industry would somehow seem incomplete without at least a few words from one or more Wall Street analysts.

When the “MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour” twice looked at Atlanta broadcasting maverick Ted Turner’s bid to capture control of CBS, for example, its lead guest both times was R. Joseph Fuchs, a Kidder, Peabody & Co. media analyst noted for his ability to translate Wall Street-speak into understandable English. When Barron‘s set out to answer a question on the minds of many investors — “What Are CBS and ABC Really Worth?” — it turned to Oppenheimer & Co.’s John L. Bauer III, who outlined in a lengthy interview his methodology for calculating the “takeout” values of major media companies. And when any newspaper property of note goes up for sale, the smart money says that dozens of journalists will be flipping through their Rolodexes for the telephone number of Iohn Morton, an affable, quotable, seemingly ubiquitous analyst with the Washington office of Lynch Jones & Ryan, another Wall Street brokerage firm.

Since March, when ABC caught everyone off guard by announcing its plans to sell out to Capital Cities Communications, Inc., for more than $3.5 billion — then the largest corporate acquisition in history not involving an oil company — the nation’s media analysts have themselves become hot properties. Clients have been clamoring for their counsel. The media companies they cover have been courting them with renewed vigor. Reporters have been chasing after them for comments, quotes, and kindred bits of Wall Street wisdom.

“It’s been an absolutely extraordinary period,” says Richard MacDonald, a broadcasting analyst with First Boston Corp. “The Friday the Turner deal got announced, I had 110 messages. It was unbelievable.” And Robert B. Ladd, a media analyst with the Chicago-based brokerage firm of Duff & Phelps, Inc., has not yet felt any dampening of the deluge. “With all the deals that are going on, it’s certainly been incredible,” he says. “There are some days I probably get more calls from journalists than I do from clients.”

No one could fault media analysts for finding an element of exhilaration in all this attention. For years, the broadcasting and publishing stocks they covered failed to ignite appreciable enthusiasm within the investment world — or, for that matter, within the nation’s business press. “Not so long ago, the whole media industry was virtually ignored by the financial community,” says J. Kendrick Noble, Jr., a veteran analyst with PaineWebber Group. “This great enthusiasm about media stocks is really fairly new.”

It used to be, in fact, that some Wall Street brokerage firms apprenticed their newly hired research analysts on media stocks, in part because their clients — major institutional investors — traditionally tended to zero in on other industries. “The market capitalization of media companies is very small,” says Peter P. Appert, an analyst with Cyrus J. Lawrence Inc. “In the total scheme of things, they have been a relatively insignificant portion of the market. Therefore, over the years a lot of institutional money managers have tended to ignore the group.”

No longer. Today, institutional investors collectively hold more than half of the stock of all companies in the broadcasting industry.

During the last decade, analysts are quick to point out, media stocks have been steady, perhaps even stellar, performers on Wall Street. Publishing stocks, for example, have outperformed the Standard & Poor‘s 500 in nine of the last ten years; broadcasting stocks have outperformed the S&P index in seven of those years. In short, media stocks have been as close to sure things as anything Wall Street sells.

“It really is incredible to think about it,” Appert says. “Warren Buffett, brilliant fellow that he is, could have bought any media stock and made money in the last decade.” (Buffett, an Omaha investor, is chairman of Berkshire Hathaway Inc., which owns huge blocks of stock in several media companies, including the Washington Post Co.; his holding company put up $518 million of the $3.5 billion Capital Cities Communications will pay to acquire ABC.)

Yet the dramatic wave of media buyouts and takeover attempts has not been fueled by the fondness of investors for stocks with long-term appreciation potential. It has been touched off by the increasing attractiveness of big media companies as “asset plays.” Traditionally, analysts placed a value on them by using a multiple of their projected earnings. Last year, however, Wall Street, after eyeing how much surplus cash many media companies had been generating, began valuing them in a new way.

The analysts’ new yardstick, “asset value,” essentially measures the potential fire-sale prices of major media companies; in other words, the total amount someone could get by acquiring one of them, breaking it up into pieces and selling each piece to the highest bidder. To arrive at a company’s asset value (some prefer to call it the “break-up” or “liquidation” value), media analysts use a multiple of its surplus cash flow instead of the traditional future-earnings multiple. As it turned out, analysts found, the market values of nearly all public media companies were way below their asset values.

As the tantalizing gaps between market and asset values transformed some media companies into red-hot takeover targets, many investors became newly enamored of media stocks as vehicles for short-term speculation. And for good reason. After Capital Cities’ offer for ABC (which represented a 60 percent premium over its market value) was announced, ABC stock shot $30 a share skyward in a single day. Amid the feverish speculation over who would be next, CBS stock appreciated so smartly that Ivan F. Boesky, the Wall Street arbitrageur who acquired 2.6 million shares of CBS stock (representing 8.7 percent of the company), cleared $17 million by selling roughly half of them a short time later.

Journalists could only follow these stories as they broke, but some Wall Street handicappers could claim, more or less, to have called the race for their clients before it had even started. Months earlier, a number of media analysts had been bullish on both stocks, which they considered to be trading at deep discounts to their asset values. In August 1984, for instance, both William Suter of Merrill Lynch and Ernest Levenstein of Shearson/Lehman American Express put ABC on their firms’ lists of ten recommended stocks to buy. First Boston’s Richard MacDonald, in an August 22 research report, recommended ABC to clients at $33 a share, suggesting that the company, could be acquired at $122 a share. (The Capital Cities/ABC deal was struck at $121 a share.)

When media analysts have something important to say’ though, most are careful to make sure their clients—and not reporters—hear it first. “Our clients pay us a fair amount of money for the information we gather,” says Cyrus J. Lawrence’s Peter Appert. “That’s our product. I’s a very tangible product that we’re selling — information, analysis, interpretation. And if you talk to the press, you’re basically giving away your product for free.”

Nearly all analysts produce in-depth research reports on the companies they follow, typically once a year, along with periodic’ updates. (Messages of more immediate import go out to clients by wire or telephone.) According to W.R. Nelson & Co.’s Directory of Wall Street Research, for example, media analysts for 11 different firms last year produced at least 29 research reports on ABC alone.

Most of the reports analysts grind out are destined for relative oblivion, but sometimes they can have an enormous impact on clients, companies, and even the careers of their authors. One now-famous case in Point: When Gannett Co. Chairman Allen Neuharth unveiled his plans for USA Today in December 1981, Watt Street publishing analysts were nearly unanimous in pooh-poohing the idea. The next month, however, Salomon Bros. analyst Edward Dunleavy weighed in with 16 pages of unconventional wisdom. If USA Today could reach certain circulation targets, he reasoned, Gannett could make the paper profitable; if not, it could be shut down without major damage to the company’s bottom line. Dunleavy’s statistical spadework was formidable: He included his own three-year financial model for USA Today, taking into account everything from market-by-market circulation potential to newsprint cost projections. As it turned out, Dunleavy’s report was right on the mark, and helped earn him Institutional Investor‘s designation as 1982’s top publishing-industry analyst.

Such a call is Wall Street’s version of a scoop, although the rewards (and risks) are much greater than anything journalism has to offer. By following an analyst’s advice, big institutional investors stand to make, or forsake, millions of dollars. Unlike the average individual investor, institutions have access to a formidable battery of securities analysts—generally at least ten and often as many as 30, all working for different firms — whose research and recommendations they can weigh before making any investment decisions. Consequently, analysts are continually being “graded” by their clients.

In theory, the analysts who earn the highest grades from clients generate the most revenue for their firms. Institutions do not actually pay for the research provided by analysts. Instead, they are expected to generate an appropriate stream of commissions for the analyst’s firm by using its trading department to execute buy-and-sell orders.

As might be expected, this system provides plenty of incentive for securities analysts to distinguish themselves from their competitors in some way, and those who follow media companies are no exception. Some analysts concentrate their energies on stock-picking, the purest form of financial handicapping. Others excel at what’s called “maintenance research” — keeping detailed and up-to-date statistical tabs on all the media companies they cover, as well as on the underlying trends that shape the industry. Yet others seek to position themselves a cut above their counterparts by more aggressively marketing their recommendations to clients or simply providing them with superior service and easier access.

“It is certainly competitive,” says C. Patrick O’Donnell, Jr., an analyst with Furman Selz Mager Dietz & Birney Inc. in New York. “Everybody’s looking for an edge. On the other hand, it’s a very civilized form of competition. It’s all very gentlemanly.”

Yet, many media analysts seem to take a certain pleasure — even delight — in running against the grain of conventional wisdom in the business, and the competition may be sharpest when it comes to stock-picking. “At the moment, I’m. recommending McGraw-Hill to my clients,” Appert says. “It’s one of my favorite media companies but not a particularly popular name on the Street of late. If I’m correct, the stock is going to perform exceptionally well.

“And if that’s not the case,” he jokes, “you will never hear from me again. I will be gone — history, as it were.”

In many respects, the similarities between what securities analysts do and what business reporters do is striking. “If you have the financial background,” Berents says, “it’s basically being a reporter on companies.” First-rate analysts are, in fact, the closest thing Wall Street has to investigative reporters.

Analysts examine complex financial statements and other documents, searching for between-the-lines significance. They scrutinize mountains of data, hoping to ferret out trends others have missed. They rely on an extensive network of sources, conducting interviews as needed. And, of course, what they write about a company and its management can have great impact.

“Some of the really good analysts are the ones who approach their information-gathering kind of like reporters,” says Jim Poyner, an analyst with the Dallas-based brokerage firm of Rauscher Pierce Refsnes, Inc. Poyner, a former reporter for the Dallas Morning News and the Dallas/Ft. Worth Business Journal, is one of a handful of securities analysts with journalism backgrounds. Others include Berents, Morton,and Patrick O’Donnell of Furman Selz. Poyner now covers two media companies, A.H. Belo Corp. and Times Mirror Co. (both of which own a television station and a newspaper in the Dallas/Ft. Worth market), and a stable of high-technology stocks for Rauscher Pierce.

The only major handicap in making the transition from reporter to analyst, Poyner found, was the sometimes daunting task of interpreting complex balance sheets and income statements — data often designed to obfuscate a company’s financial condition. On balance, however, Poyner feels his experience as a business reporter has shaped how he approaches research, interviews,and even writing as an analyst.

“As a reporter, it was my experience that the chairman of the company was just going to give you big-picture generalities that were not going to be very quotable or very informative,” he says. “You’d talk to other people to find out what was going on. I’m very keen now on talking to the people who are in the trenches every day. And I think some analysts are guilty of just talking to the head honcho.”

In his days as a business reporter, Poyner says that analysts frequently called him for information about the companies he covered. Now, in a way, the tables have turned: Reporters call him for his views as an analyst. Yet, Poyner sometimes finds it something short of satisfying. “In my experience, when reporters talk to an analyst they typically want just a quote,” he says. “And they’re not too damn picky about what goes with those quotation marks.” Few of them, he says, routinely ask analysts how closely they follow a company and its competitors or whether the company is on their recommended list — factors that might shape whether an analyst’s views ought to be accepted at face value.

Although some media analysts say they simply are not interested in being interviewed by reporters and quoted in their stories, others, like Berents, believe the exposure is advantageous. “It’s important to get quoted in this business because it gives you greater visibility,” he says. “If you can build up a credible name over time, it’s very important to you.”

As for visibility, there is also a kind of snowball effect at work: The more an analyst is quoted, the more calls he is likely to get from reporters in search of a source. “I think reporters see your name in some other press piece,” says First Boston’s Richard MacDonald, “and then they think you’re a target.” Another reason some media analysts are quoted so frequently is that they enjoy talking with reporters. PaineWebber’s Noble, for one, says he feels a certain kinship for the profession and often picks up information useful in his work as an analyst. “I learn as much from reporters, if not more, than I tell them,” he says. “But we are by no means a monolithic profession. There are some who couldn’t be bothered. There are some who work in firms that have a house policy: ‘You shall not talk to reporters.’ “

Some analysts, such as Furman Selz’s Patrick O’Donnell, say the volume of incoming calls from reporters is simply too onerous. “I get a lot of calls from reporters, most of which I can’t answer,” he says. “I mean, I could be on the phone from 8:30 in the morning until 5 o’clock at night and still not have all my calls returned. My primary responsibility is to the clients of the firm, and everything else comes after that.”

There is also a downside to the equation, as Berents points out. “You could have all the publicity you want,” he says, “but if your stocks go to hell, people are going to ignore you.”

Analysts, after all, make their share of mistakes. When the prestigious Des Moines Register and three small sister papers went on the auction block late last year, media analysts, after taking a long look at Iowa’s shrinking population and the depressed Midwestern farm economy, figured the top price for the package would be $150 million. The winning bid, tendered by Gannett Co., was an eyebrow-raising $200 million.

“Reporters tend to put analysts too much on a pedestal,” says Jim Poyner. “If they’re not real astute on numbers, analysts may be able to help them out in that regard. But as for passing judgments on companies and markets, hell, reporters can go out and get information that’s as good or better.”

In comparing the experiences from old profession to new, Poyner draws one other lesson. “If I were a reporter today,” he says, “I would rely much less on analysts as sources of information.”