A Compendium of Small Cons

And Now, For Our Next Witness. When the Justice Department needed to show in U.S. District Court in 1976 that Metro subway tunnels would not threaten the foundation of the new Continental Trailways building at 12th Street and New York Avenue, N.W., it turned to Robert L. Redell.

Redell, a construction engineering expert with degrees from Michigan State and Marquette universities, had worked on a variety of impressive projects: a desalinization plant in Israel, the Granada Hilton hotel in Spain, the “nuclear acceleration facility at the Edgewood Arsenal, Maryland,” the Rockefeller Center in New York, and a “pneumatic conveyance system through the mountains from Bolivia to Peru.”

Redell earned more than $10,000 by testifying for the federal government in various cases as an expert witness. Then he was discovered to have faked everything but his name.

The One-Man Bandwagon. In 1942, two Washington newspapers, the Daily News and Times-Herald, began selling General Douglas MacArthur buttons as a promotional gimmick.

The public’s phenomenal response — more than 500,000 buttons were sold — apparently caught the enterprising eye of Joseph H. Leib. He rented a hole-in-the-wall office in the National Press Building and sent out a blizzard of news releases to solicit contributions for the “national Committee Headquarters of the Draft MacArthur for President Clubs.”

“Does General MacArthur know you are running him for President?” a visiting newspaper asked.

“No, but Mrs, MacArthur knows about it,” Leib answered. “She knows about it through a friend who was told about it by a friend of mine.”

The Aluminum Foil. James G. Fuller, a local con many and phony check artist, conceived his boldest swindle while residing in the D.C. jail.

Upon his release, Fuller formed the Kalunite Corporation and told prospective investors that he could obtain control of bauxite ore deposits in Utah and make millions through a secret aluminum-extraction process. Through a second bogus outfit, Engineer’s Group, Inc., he sold nonexistent wartime contracts at wholesale. Fuller bilked Washington builders of at least $60,000 by promising them they would receive contracts on defense housing projects after paying for the necessary “engineering surveys.”

James M. Curley, a former governor of Massachusetts, was one of several prominent Washingtonians who unwittingly lent their names to the ex-convict’s letterheads. “He was one of the most interesting and intelligent men I ever met,” Curley told a reporter. “He could discuss anything from chemistry to art.”

If You Can’t Beat ‘Em, Join ‘Em. Within a year of hanging out his shingle at 2514 14th Street, N.W., Lawrence A. Harris had earned a reputation as one of Washington’s most aggressive criminal lawyers by tackling some of the most difficult and desperate cases on the District Court’s calendar.

He left Washington abruptly in 1961, however, amid gossip in the courthouse corridors that he looked remarkably similar to a convict pictured in a national magazine. Little wonder: “Harris” turned out to be Daniel Morgan, a convicted robber, housebreaker, and vagrant.

At Morgan’s trial, three former clients — all of them on death row — testified that they were pleased with his work. Morgan served, of course, as his own attorney.

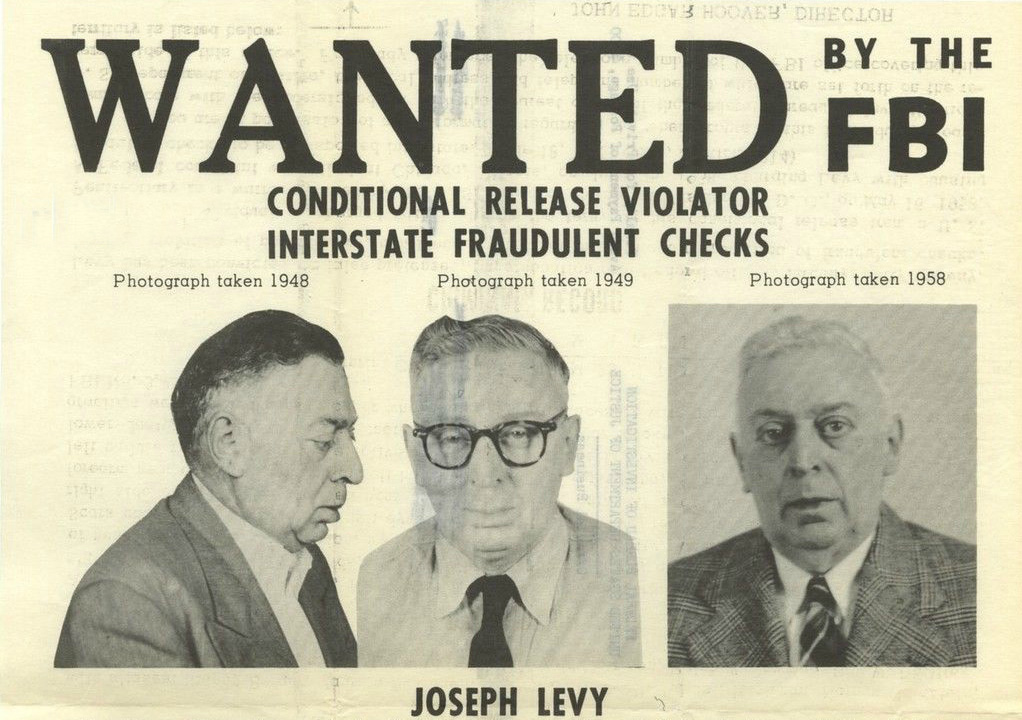

Many Unhappy Returns. Joseph Levy, a bad-check artist who regularly passed through Washington, had a penchant for patronizing the $50 windows at race tracks.

To support his proclivity, Levy employed this modus operandi: He purchased expensive gifts for well-known government officials, wrote rubber checks considerably larger than the price tags, and pocketed the difference. To ease the minds of suspicious merchants, he penned personal notes to accompany the gifts. Even the Eisenhowers were on Levy’s shopping list: He sent French perfume to Mamie at the White House and a case of Scotch to Ike. Vice President Richard Nixon received an expensive set of golf clubs, along with this intimate message: “Dick, beat the boss.”

Levy was arrested at Churchill Downs in Louisville on April 30, 1953. “Some Washington residents,” reported the Evening Star, “are still receiving the ‘gifts’ from different parts of the country.”

You’ll Hang for This. Richard F. Cleveland, the son of former president Grover Cleveland, was visited in 1932 by one Dr. F.D. Vernon, who claimed to have an oil portrait of his father painted by noted artist Paul Bersch. The president’s son paid $150 for it.

“Dr. Vernon” turned out to be Washington con man George J. Shepard, who specialized in bogus-portrait swindles. Three years later, Shepard approached Cleveland again, this time using his real name, and was promptly arrested. Even on the way to jail, Shepard continued to claim he was a physician and told authorities he was suffering from an incurable disease.

And Before That, He Sold Ice to Eskimos. In 1933, Ernest Nelson convinced at least forty-three Washington merchants to contribute money to a fund to “keep the Arlington Memorial Bridge and to finish the project.”

The project had been completed nearly a year earlier.

The Old Army Game. One day in early 1942, Maynard Kimberland began his search for a military job in style. He showed up at the War Department’s motor pool, proclaimed himself to be “General Kimberland,” and requisitioned a Packard limousine and chauffeur.

“The ‘General’ blazed a glittering Washington trail,” a local newspaper later reported, “and had a long list of hotel doormen and bellhops giving him snappy salutes.” Commander H.G. Hemingway of the U.S. Coast Guard complained later than whenever he had dinner or cocktails with “General Kimberland,” it always seemed that he was stuck with the check.

Main Story: Capital Cons

This article originally appeared in the July/August 2000 issue of Regardie’s Power.