Letter from MHQ: The Can-Do Commander

During World War II, Major General Ira T. Wyche soldiered in the shadow of such towering figures as Dwight D. Eisenhower, Omar Bradley, and George S. Patton Jr., which may help to explain why no biographer has ever told his life story and why so few histories of the conflict cast him in any kind of central role. Another reason is that Wyche never really aimed to be in the spotlight, probably because he was so busy tending to the troops he commanded and planning how the 79th Infantry Division, which he led, would take out the formidable German forces in its path.

Wyche was born in 1887 on Ocracoke Island, North Carolina, and was raised by his grandparents after his parents died. His brother entered the ministry, following in the footsteps of their father, a Methodist pastor. Ira, however, decided to make a career in the military.

Wyche entered the U.S. Military Academy in West Point, New York, at age 19. Despite his small, wiry frame, “Billy,” as he was known by his classmates (though some dubbed him “Witch”), was more of a standout in athletics than in academics, playing football, baseball, and polo. He was also a leading member of the glee club and the cadet corps choir, and he performed in the 100th Night Show, a musical-comedy revue.

Howitzer, the West Point yearbook, gave him this writeup: “West Point has changed you, Billy. You once were a reticent little Tar-Heel with a wise head on your shoulders, and a smile of understanding that told no tales. But now, ah, now, you little cherub, every femme that sees you wants to bite your rosy cheeks.”

On graduating from West Point in 1911, Wyche was commissioned a second lieutenant in the U.S. Army’s 30th Infantry Regiment. He was later detailed to the Mounted Service School at Fort Riley, Kansas, and served for two years with the cavalry on the Texas border. After joining the American Expeditionary Forces in 1917, he was promoted to lieutenant colonel and sent to France, where he commanded an artillery unit on the Western Front. Later that year he returned to the United States to help train gunners, and for the next 25 years he steadily moved up the ranks.

On June 15, 1942, Wyche was appointed the commander of the 79th Infantry Division. As Roy Morris Jr. details in this issue’s cover story, which begins on the next page, Wyche’s “Fighting 79th” spearheaded the capture of Cherbourg, fought its way across France to attack the Siegfried Line, crossed the Seine River, and then made its way to the Rhine River and the Ruhr Valley. Some said Wyche’s infantry movements resembled cavalry sweeps.

Nearly every day, Wyche made the rounds of all the command posts in his area, checking in with his men, asking questions, giving advice and encouragement, and even interviewing German prisoners. Soldiers, unaccustomed to seeing such concern on the part of commanding officers, dubbed him “Papa Wyche.” At a dinner in honor of his 57th birthday, Wyche made it a point to toast “the men who are responsible for the success of the division” and “the men in the foxholes.”

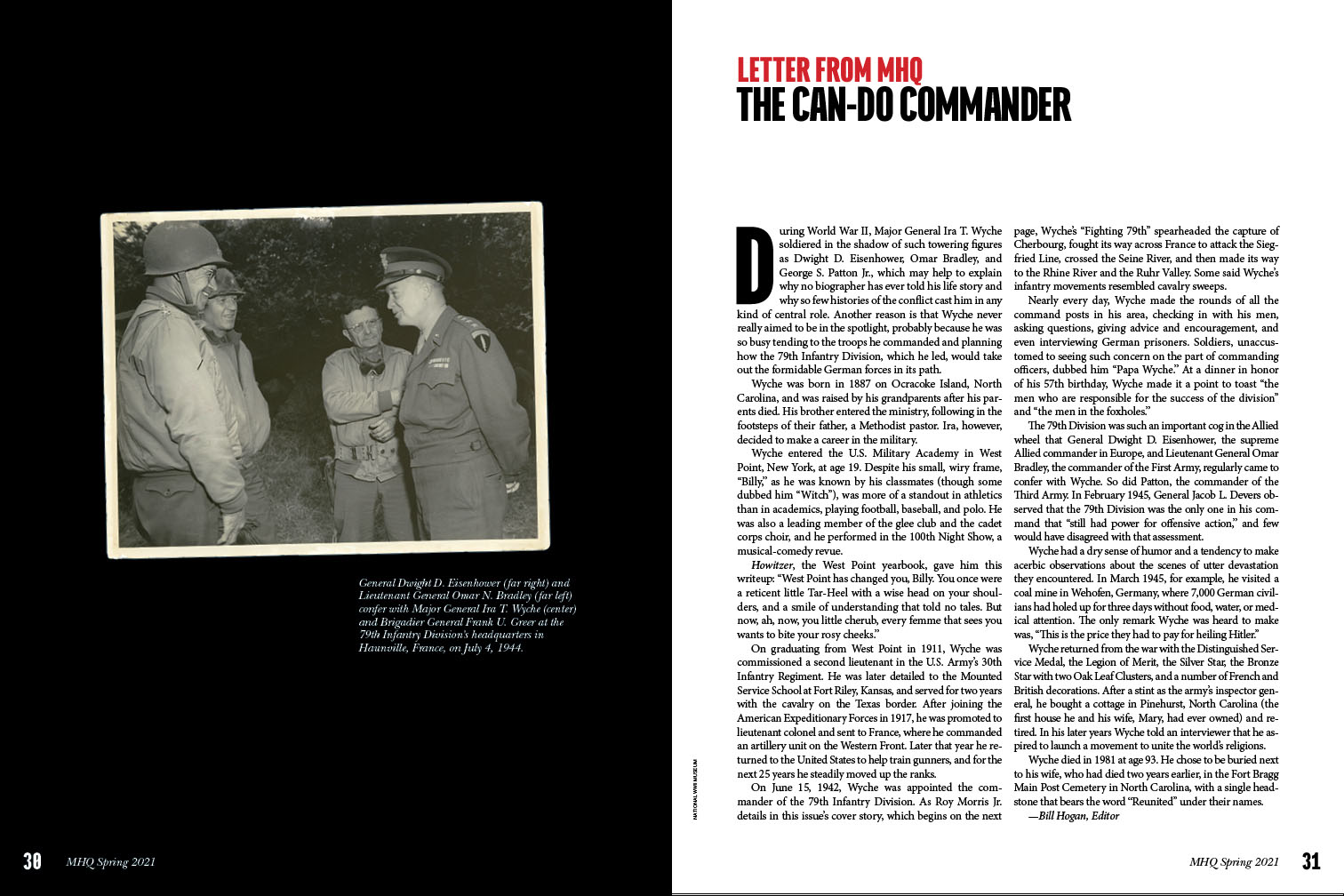

The 79th Division was such an important cog in the Allied wheel that General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the supreme Allied commander in Europe, and Lieutenant General Omar Bradley, the commander of the First Army, regularly came to confer with Wyche. So did Patton, the commander of the Third Army. In February 1945, General Jacob L. Devers observed that the 79th Division was the only one in his command that “still had power for offensive action,” and few would have disagreed with that assessment.

Wyche had a dry sense of humor and a tendency to make acerbic observations about the scenes of utter devastation they encountered. In March 1945, for example, he visited a coal mine in Wehofen, Germany, where 7,000 German civilians had holed up for three days without food, water, or medical attention. The only remark Wyche was heard to make was, “This is the price they had to pay for heiling Hitler.”

Wyche returned from the war with the Distinguished Service Medal, the Legion of Merit, the Silver Star, the Bronze Star with two Oak Leaf Clusters, and a number of French and British decorations. After a stint as the army’s inspector general, he bought a cottage in Pinehurst, North Carolina (the first house he and his wife, Mary, had ever owned) and retired. In his later years Wyche told an interviewer that he aspired to launch a movement to unite the world’s religions.

Wyche died in 1981 at age 93. He chose to be buried next to his wife, who had died two years earlier, in the Fort Bragg Main Post Cemetery in North Carolina, with a single headstone that bears the word “Reunited” under their names.

—Bill Hogan

This article was originally published in the Spring 2021 issue of MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History.