Opening Round: French 75

In 1898 the French army introduced the world to a fearsome new piece of artillery: the Canon de 75 modèle 1897. French soldiers quickly dubbed it the Soixante-Quinze (“Seventy-Five”) in a nod to its 75mm bore, and in time the gun would become commonly known as the French 75. The Germans who encountered the gun at the First Battle of the Marne in September 1914, however, branded it the “Black Butcher,” and little wonder: The French 75 had been specifically designed to rapidly rain time-fuzed shrapnel shells on advancing enemy troops. As the first field gun with a hydraulic recoil mechanism, it did not need to be resighted after each shot and could typically fire 15 rounds a minute at a designated target more than five miles away. An experienced crew, using progressive traversing along with small changes in elevation, could terrorize the enemy with fauchage, or “sweeping fire.”

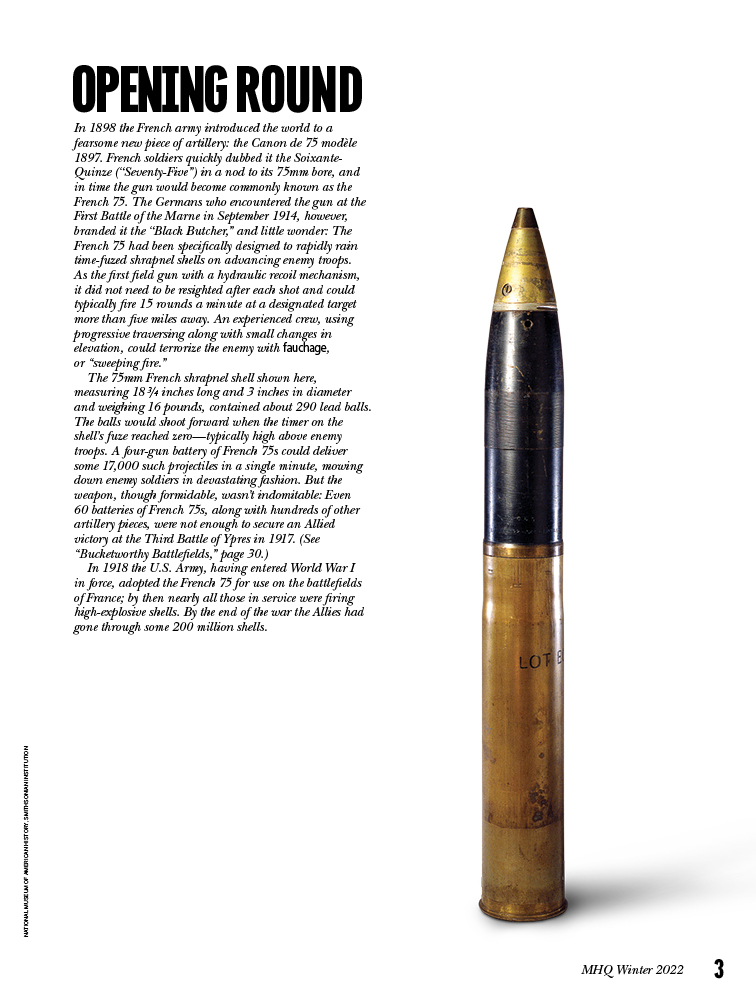

The 75mm French shrapnel shell shown here, measuring 18 3/4 inches long and 3 inches in diameter and weighing 16 pounds, contained about 290 lead balls. The balls would shoot forward when the timer on the shell’s fuze reached zero—typically high above enemy troops. A four-gun battery of French 75s could deliver some 17,000 such projectiles in a single minute, mowing down enemy soldiers in devastating fashion. But the weapon, though formidable, wasn’t indomitable: Even 60 batteries of French 75s, along with hundreds of other artillery pieces, were not enough to secure an Allied victory at the Third Battle of Ypres in 1917. (See “Bucketworthy Battlefields,” page 30.)

In 1918 the U.S. Army, having entered World War I in force, adopted the French 75 for use on the battlefields of France; by then nearly all those in service were firing high-explosive shells. By the end of the war the Allies had gone through some 200 million shells.