How Money Makes Harvard and Vice Versa

GREAT GOOD FORTUNE

How Harvard Makes Its Money

By Carl A. Vigeland

Houghton Mifflin. 245 pp. $18.95

“WHEREAS THROUGH the good hand of God many well devoted persons have beene and dayly are mooved and stirred up to give and bestowe sundry guiftes legacies landes and Revennewes for the advancement of all good literature artes and Sciences in Harvard College in Cambridge . . .”

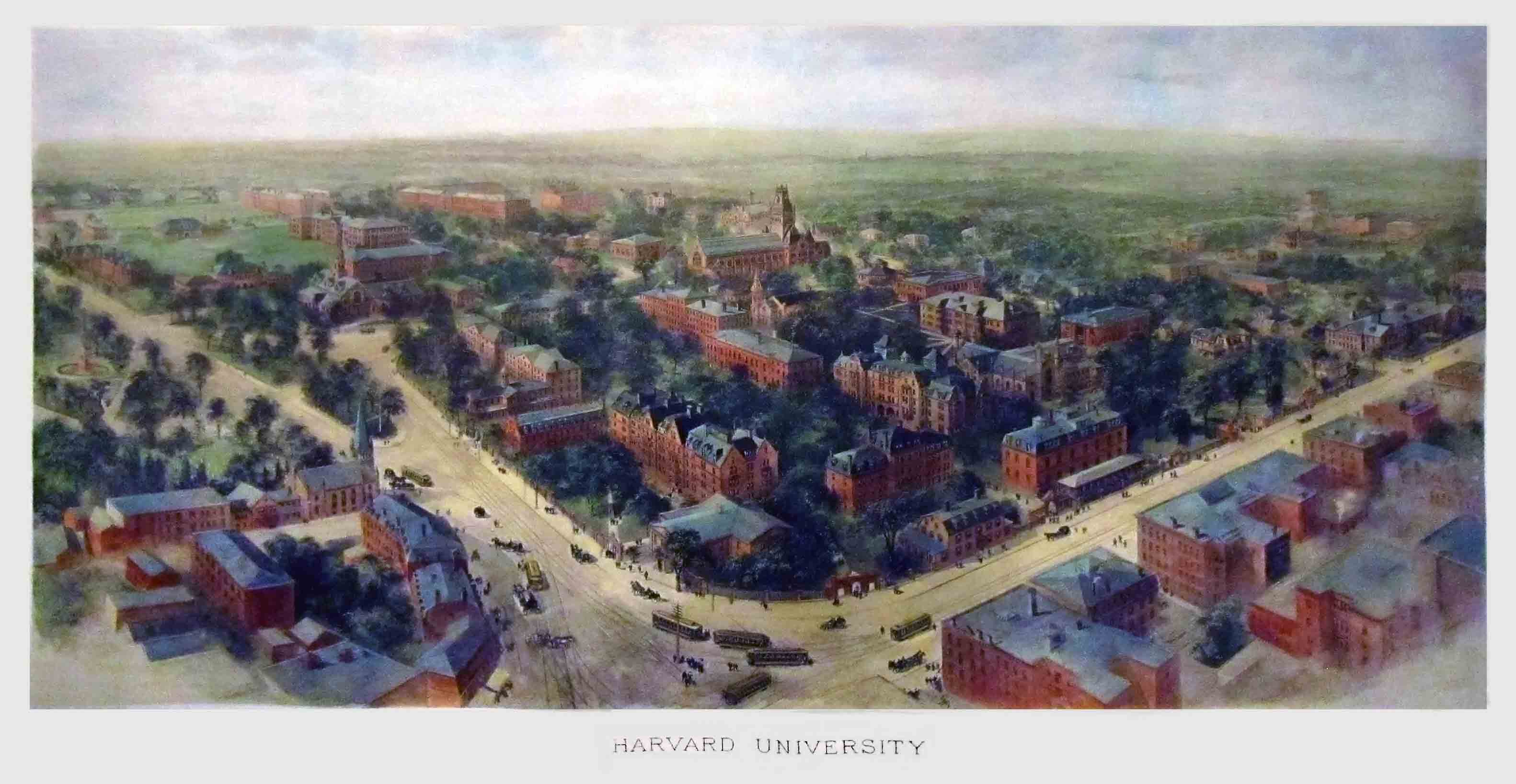

So it began, in 1650, with this corporate charter. Twelve years after the death of John Harvard, a poor English minister who had left the two-year-old college his library, half of his estate, and, as it turned out, his name, Harvard became — figuratively speaking — Harvard, Inc. And for more than 300 years since then, the hand of God, apparently, has remained good to Harvard. It is the oldest self-perpetuating corporation in the Western hemisphere, the situs of what is widely believed to be the finest education money can buy, and happy recipient, still of sundry gifts, legacies, lands, and revenues.

Great Good Fortune, by Carl Viegland (Harvard ’69), is mostly about money — how Harvard raises it, manages it, spends it. Money, after all, has made Harvard, once an intimate and insular academic community, into something else altogether.

For better or worse, that something else is big business. As Vigeland’s intricate and engaging account shows, Harvard these days is more of a conglomerate than a community. Its endowment, nearly $3 billion at last count, is managed by a wholly owned subsidiary with 100 employees and an annual budget of more than $7 million. Its debt service alone, at $50 million-plus a year, surpasses the entire budgets of many fine colleges. And Harvard’s sense of self is defined, willy-nilly, by its wealth: The school’s 350th anniversary “spectacular, to be celebrated September 6 in Harvard Stadium, is being produced and directed by Tommy Walker, whose pyrotechnic and special-effects wizardry dazzled crowds in New York on Liberty Weekend in July.

But Harvard’s real business is higher education, which has come to resemble any other fiercely competitive industry in its approach to product differentiation, marketing, and pricing. Harvard cannot afford, for reasons of equity and image, to price itself out of the market, so it charges what the market will bear. Because revenue from students covers only about one-third the cost of educating them, however, it must look elsewhere to keep its book in balance. And elsewhere, for the most part, means Harvard alumni — some 200,000 of them in all.

Vigeland’s penetrating look at Harvard’s formidable fundraising apparatus focuses on the Harvard Campaign, which brought in more than $350 million between 1979 and 1985. Most telling is a peek inside the telephone boiler room, where Harvard volunteers are being taught the four commandments of fund-raising: open, engage, ask, and close. These pitchmen and -women were expected to complete, on average, one telephone solicitation every 12 minutes, guided by such succinct advice as this: “Take your time. Listen. Don’t rush the conversation. Be alert to the large gift.”

AH, THE large gift. Whenever Harvard’s fund-raisers run across an “alumnus of rumored or documented means,” as Vigeland delicately puts it, they see to it that the actual asking is executed by a Harvard alumnus of considerable wealth. It simply would not do, the theory goes, to have a Main Street minister put the pinch on a Wall Street arbitrageur.

Over the years, Harvard has been so successful in these pursuits that managing its mammoth investment portfolio long ago became a game of extraordinarily high stakes, a game in which split-second decisions can mean millions — plus or minus. Since the mid-1970s, a subsidiary of sorts, the Harvard Management Company, has played that game and played it well. Consider this assessment of its work, culled by Vigeland from a treasurer’s report: “The Management Company has been a leader, breaking new ground in many previously untested and profitable investment areas including stock and bond loans, options, financial futures, bond and stock arbitrage, real estate, venture capital, leveraged buyouts, risk arbitrage, indexed portfolios, and a variety of new fixed-income instruments.”

Some of these techniques generated E-Z money, and lots of it. George Sigular, Harvard’s associate treasurer and a man with a knack — maybe even genius — for dreaming up new ways to turn a profit, first had the idea of leveraging some of Harvard’s sizable holdings through the highly profitable practice of security lending. In virtually no time, Harvard was lending a million dollars in securities every month; within one year, nearly one-third of the stocks lent worldwide were from the Harvard Management Company.

There’s also the legendary maestro of Harvard’s trading desk, Bing Sung, a pioneer in his profession whose term of endearment for fellow traders is “Sweetie.” Sung puts his finger, better than anyone else, on why Harvard has been so successful in winning the games Wall Street plays. “We are like a casino,” he says, “because we have deep pockets and patience. We can weather the storm.”

Harvard always has. Its reputation — Harvard has produced more U.S. presidents, Supreme Court justices, members of Congress, and top corporate executives than any other institution — precedes it everywhere, and that’s a powerful advantage in the marketplace. Yet Vigeland suggests it may be slipping just a bit. “Harvard is playing a faster, more sophisticate and complicated game,” he writes, “and it is no longer declared the winner before the contest begins.”

Maybe so. But as long as it takes money to make money, Harvard’s competitive edge would seem to be plenty sharp.

This review originally appeared in the August 24, 1986, edition of The Washington Post Book World.